Lee Mitchell

“Lo and behold, Al Green came out with ‘I’m So Tired of Being Alone’….Those songs I was supposed to sing….I just knew that it would have been a successful thing for me.”

In a parallel universe Lee Mitchell – not Al Green – emerged as the top male soul star of the ‘70s. Lee hooked up with producer Willie Mitchell (no relation) in Memphis and they recorded an album at Royal Studios. It was released on Willie Mitchell’s Hi Records. And Lee Mitchell became a household name, while Al Green never caught a break and turned to the ministry instead.

The above scenario did not come to pass in our universe, where an unexpected death in the family kept Lee Mitchell from his date with Willie Mitchell and quite possibly from fame and fortune. When he told me about his blown opportunity, Lee Mitchell showed no trace of bitterness. On the contrary, he maintained his smiling, upbeat countenance, grateful to be where he was on that fine spring day in Boston in 1998 – and grateful for his ministry, his loving wife and children and his tidy home on a trash-lined dead-end street in Dorchester, where his wife Mary served us a fried chicken, French fried potatoes and salad for lunch.

Lee Mitchell seemed a contented man. He had found his calling preaching and singing praises of the Lord. He was propelled to return to the church, ironically enough, after suffering the same fate as Al Green: a violent attack by an angry girlfriend. Both would forsake their r&b careers – Al in Memphis and Lee in Boston – and become reverends determined to lead their own congregations.

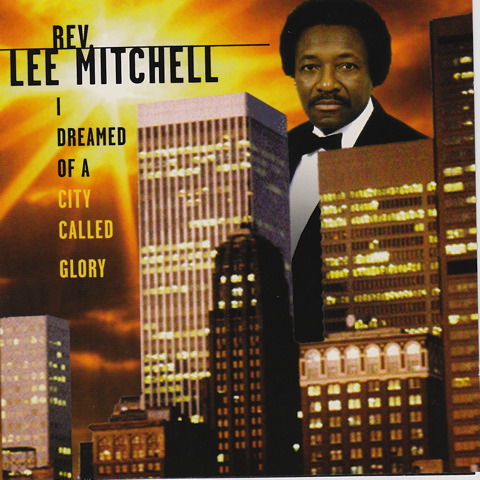

I first heard of Lee Mitchell shortly after he recorded “I Dreamed of A City Called Glory,” the first of the three albums he made with the help of veteran Boston musician Barry Marshall, all released on Mitchell’s own Hersey label (his birth name was Hersey Lee; you can hear samples of and find purchasing information for Mitchell’s hard to find CDs here). “I Dreamed of A City Called Glory” was a gospel album, but musically it harked back to classic ‘60s and ‘70s soul. A few years later Marshall convinced Mitchell put out a non-gospel album, “Sings Songs of Love.” And finally, as Bishop Lee Mitchell, he released a set of twelve gospel originals, “I Found the Answer,” in 2009.

It would be his final recording. After a period of declining health, Mitchell died on December 28, 2014 at age 75.

April, 1998

In the dining room of his home off Columbia Road in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Take me back go the beginning. Tell me about how you started out.

From the time I was a boy there was something that compelled me to sing. I grew up on the farm in North Carolina [where Mitchell was born July 12, 1939]. My dad worked the farm. My older brothers, they would help him. I was the fifth child. A lot of times I couldn’t take on the jobs they took on in the fields. I was small, I just couldn’t do that. So I would have to help mama most of the time. My mother was the washing-est lady I’ve ever known. She’d wash every day. I’d say, “Mama, why you washing, you washed yesterday?” [laughs]. She believed in keeping everything clean. I’d get so tired of washing because then you’d have to draw the water out of the well, bring it to where she was and boil it in a big ol’ pot. Then she’d boil the sheets and things like that. It was a chore. Then I’d have to feed the cow, feed the chickens, feed the ducks, feed the geese, milk the cow, then take the cow where she could eat so we could have milk the next night. Now my dad and my older brothers would work out someplace, and come home late at night. But during the daytime I would have to do all these things. And when school was on, I’d have to milk the cow before I’d go to school in the morning. And I tell you, boy, I was in a hurry. I got up late maybe, put the cow in the stall, get everything ready, get the bucket and get it going and the cow kicked the bucket and spilled the milk [laughs]. I’d have to start all over again. I can still remember that cow and those things I had to do when I was young.

But it learnt me a lot of things about life and about nature, animals and how they function. When you live in the country on the farm you get a different perspective on life than you do in the city. In the city, everything’s moving day in and day out. You don’t have time to focus on nature, the earth. In the country nuthin’s moving [laughs]. You can focus on all those things.

The whole time I’d milk the cow and do these things I’d sing all the time. My mama sent me to the store to get things and I’d be so busy singing by the time I got to the store I forgot why she sent me. They didn’t have telephones at that time, so I’d have to go back to the house to ask her what I was supposed to bring her. Oh, I got in trouble from that singing. Singing has done a lot for me, but it’s got me in a lot of trouble also.

Were you eager to leave the farm?

I couldn’t wait to graduate so I could leave the farm. I had enough of the farm. I wanted to see what other things were like, especially the city. I had an aunt living in Boston. She promised that I could stay with her. I’m grateful because she gave me the opportunity to come to Boston [in 1958] – Roxbury, over on Washington Street near Egleston.

Did you sing when you first got to Boston?

Well, my cousin had a quartet [the Power Lights] when I first came here. He knew about my singing ability. Sometimes when they sing they asked me to come along and they’d let me sing a song. Because of that, other people had a chance to hear me. Then this group that was professional, the Bibletones, they asked me to come when their lead singer [Bill Moss, who formed his own group, the Celestials] was leaving. That was a big undertaking. He was a songwriter and an experienced singer, he had all the gifts. Have you heard of the Clark Sisters? He was their uncle. They must have had a repertoire of 40 songs. They got me in there before he left and he taught me, drilled me, showed me different techniques about singing that I never knew. Because he was a pro. And I just loved it. After he showed me, they had big engagements coming up down south and we started to tour. They said I was ready. I don’t know if I was or not, but I went and it was a successful tour. I started to record.

My first recording was in 1961, a gospel song, “Christ Is All the World to Me.” We recorded that song and after we had toured, in 1964, I became ill. I developed ulcers. I couldn’t sleep. I went to the doctor and he couldn’t find the problem. It got to me. I decided to leave Boston. I had friends in California. I remember the time so clearly because Sam Cooke got shot [December 11, 1964] when I was on my way to California. I heard it on the news. I drove out and lo and behold when I arrived in L.A. it was the second day of the Watts riot [August 12, 1965]. The city was still burning. People were driving down the streets 100 mile per hour. There was a curfew. Nobody could go out past nine o’clock. It was a chaotic situation. but I found the people that I knew. I started to look for work after about two weeks. I had no specific skills, but I had a new car. I’d listen to the radio at night and they was telling about some show going on where the first prize was one hundred bucks. I said, “I could use that.” When I got to the club, the person who was in charge, the emcee and I, sang that Sam Cooke song, “A Change Is Gonna Come.” I got first prize and the hundred bucks. I came back the next Wednesday night and did the same song and won again. The next Wednesday they wouldn’t let me enter. They said, “No, you a professional.”

But from that I got introduced to other people. They said I could get a job in clubs singing rhythm and blues. I liked to experiment, to explore. Sam Cooke let me know that I could sing this as well as gospel, he made me aware that I could do this.

It got to the place where I became domineering. I was singing any kind of song, all of the blues songs that were out, and I could do them well. So I was never out of a job. I was singing in a place in Compton and an old man, J.R. Fulbright, a waitress says, “This man wants to talk to you.” Old man with grey beard, grey hair. He said, “I wasn’t going to fool with more artists, but, y’know, you’re good. You have something in you. Come out to my house and talk to me tomorrow.” So the next day I go to his house and he started showing me posters on James Brown, Etta James, Big Mama Thornton, Lowell Fulsom, T-Bone Walker. He says, “All of these are my artists. I helped them and I want to help you.” [Fulbright was an L.A.-based talent scout and producer; best known for discovering zydeco great Clifton Chenier. Fulbright recorded Chenier’s first singles for his own Elko label, before bringing him to L.A., where Chenier signed with Specialty Records.]

He helped me put together the Lee Mitchell Revue, two go-go girls and a band behind me. We played Barstow, Bakersfield, all the way to San Francisco. Then we’d come back and go up to Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, Canada. The next year we go to Arizona, El Paso, Odessa, Corpus Christi, San Antonio, Victoria, Brownsville, that whole area and back again. He said, “If I can get you known, we can get us a record deal.”

Sure enough, Duke Records out of Houston, Texas, [owned by] Don Robey. He had four labels, Backbeat, Sure Shot, Duke and Peacock. But see, when I look back at it I can see that something wasn’t right in that. What happened, I really had a hot band and a good show. We packed every place we go. This time, we had to go to Houston. We arrived in Houston at two in the morning. We had two station wagons packed with people and equipment. We go into a club and we’re all in there for maybe 10 minutes and a guy comes in and says, “Hey, whose station wagons is out there? A guy is ripping you off.” We went out there and they had stole our instruments. We’re young guys with no money and now no instruments. We had no way to buy equipment. That’s when I met Don Robey. He gave us money to get some equipment. I was indebted to him. But he was fair.

I started recording for that Sure Shot label. My first recording was “You’re Gonna Miss Me When I’m Gone” and “Where Does Love Go (When It Dies).” I did three singles for Sure Shot, which passed to ABC after Robey’s death. But they’re still in the vaults, only the one got released. It was good for me because now there was a record to play when I’d come into a town. I started to build up a following. Each year I’d come back. So this year I go down, they say, “Let’s do something different. There are all these hits out of Memphis, Sam and Dave, Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes. He says, “We’re going to send you there and let this Willie Mitchell do an album on you. I said, “Great.” I got my ticket and flew into Memphis and checked into my hotel. The next day I get a call. My oldest brother had passed away. I called Mr. Robey and said, “I have this emergency. I have to go to my brother’s funeral tomorrow. He said, “No no no. You can’t go. You got to stay and do that recording.” I said, “Well, I’ll go and come back.” He says, “No, I don’t want you to leave.” I had a diamond ring on my hand. I used it to get a plane ticket. I figured my brother only dies one time and I ought to be there. Mr. Robey found out and said I was getting too big for my britches. No more deal. I left and went back to California. Lo and behold, Al Green came out with “I’m So Tired of Being Alone.” Willie Mitchell. Those songs I was supposed to sing. I could sing all those songs.

How did you feel when you heard Al Green come out and have a big hit with Willie Mitchell after you missed your chance?

I just knew that it would have been a successful thing for me. But I looked at the circumstances. Shouldn’t I have gone to my brothers funeral? My family would have been hurt. Wasn’t that worth more than money? I was brought up in a Christian home. My dad’s still a deacon. I just felt I should go. I thought no man should dictate to me what I should do. And why couldn’t I go and record when I come back? So I went back to California, started touring again and recorded for some other labels [including what many consider his greatest song, “How Can You Be So Cold?,” released by HL&M Records].

After all that went on I formed a band out of Anchorage, Alaska called Black Express. We toured from Alaska to Alabama. This band was so hot. We set down in Birmingham, Alabama to record. This other guy, Jack Frost, who was governor Wallace’s press secretary, he wrote a lot of love ballads for me. We started to tour. We had “You and You Alone,” which was a big song in the southern states. In 1973 I got shot. After that I said, “This is not good for me.”

Whoa. How did you come to get shot?

There was a lady I was involved with. We just had a squabble and I kept my gun in my car. She stormed out of the house, got the gun. When she came back, I didn’t think nuthin’ of it. But she came back and opened the door. I was sitting on the low seat and –pow! – she shot me here [Lifts up his pants leg and points to a scar on his calf]. I had to make that change.

A friend of mine from the Bibletones called me and said, “We want you to come sing with us on our anniversary.” We’d lost touch, but they found me in the hospital through my dad. I came to Boston for the anniversary. I started migrating back and forth and eventually I came back [in the mid-’70s]. I had a nightclub in Alabama, I gave it all up. It didn’t mean nuthin’.

Did getting shot convince you to start singing gospel?

Well, getting shot put it in my mind not to sing r&b. I had enough of that, though I had built up a clientele where I could work all the time. I was a drawing card. Promoters were calling me. I had no problem getting jobs, but driving up and down the highway, I tell ya….I thought I’d never come to Boston again, but at the time he called me, I’d been shot, my mind was turning. I stayed with my mom for a month while recovering. I got to see where I come from. I saw I had got caught up in circumstances in these nightclubs and it had become a way of life. I had a nightclub, go-go girls, the whole bit. It had sucked me right in. I had to get out and make that transition. I had to leave all of that. It was hard, but it did come. That same record I recorded in 1961, the manager of the Bibletones had a radio program that had been on the air all these years playing that record as the theme song, “Christ Is All the World to Me.” Every Sunday. They had their anniversary at Boston Technical High School and I sang the opening line, “Christ is all,” and you couldn’t hear nuthin’ in that auditorium for 10 minutes they were yelling so loud. I got a response. It was really something.

And so you left your rhythm and blues career behind?

[Nods] Out of all those years, my biggest hit came after I got out of the business. We would do production work at the studio [in Alabama at Neil Hemphill’s Birmingham Sound Studio ], put down tracks, lead vocals, experiment, trying to get a hit. Frederick Knight [of “I’ve Been Lonely For So Long” renown] wrote the flip side [“Best Shot’] of my hit song. In 1978, they released that song, “So Called Friends.” It was my biggest hit. A company out of Chicago bought it [Track Down Productions, which released “So Called Friends” on the Full Speed Ahead label]. I was driving through Baltimore and the record comes on. [Mitchell sings:] “So called friends, you better leave them alone.” I said, “That’s me! What’s going on here?” Lo and behold, a company out of Chicago had made a deal and sold it right out from under me. Biggest song I ever had – after I got out of the business. “Take My Best Shot,” that was the flip, Frederick Knight wrote it. I never got paid, but there are so many horror stories out there. That’s why I formed my own record label [Hersey Records], my own publishing company. Now no one can come in and just take it.

In addition to singing in church, Barry [Marshall] told me you’re going to be doing that Gospel Brunch they have at the House of Blues. I know that this is something that’s controversial in the gospel community, with some folks saying that gospel music should not be performed in places where they serve alcohol. But others say that it’s taking the message of gospel where it’s needed most.

That’s the philosophy I have. Jesus didn’t come to save the saved. He came to save the sinner. The people in the church are already saved. We have to reach out to those who are not. I had to have a meeting with [House of Blues booker] Teo Leyesmeyer. I had reservations, but I had a chance to minister to people who won’t hear me sing in church because they don’t go to church. I saw it as a chance to reach out to people. I see the gospel as something so important, you need to prepare your singing. I’m old now. If I haven’t got it right by now I’m not going to get it right. You have to put the time in so when people hear the gospel they go, “Wow!” You have to have something overwhelming to win a soul.

What sort of group will you be performing with?

I have four musicians and three background vocalists, including my two daughters.

Where is your ministry located now?

I was right around the corner from my house with Preachers N Concert. What happened was three preachers came together – myself, the one that’s there now and another one. We all had similar backgrounds, they were also singers before they came ministers. We were called by a woman who had a dream about it, and she kept calling and calling until they put Preachers N Concert together. But then one preacher left for another church and the remaining preacher got married to a young wife and her interference, it caused some problems and led me to leave.

Now I am part of the Salvation Christian Center, which is part of the Church of God in Christ, which is the national organization. We’re hoping to be very visible soon. We’re in the preparation stage. I’m doing a lot of counseling now, but in the future, soon, we’ll be very visible in the community. I’m looking forward to it, because there’s a lot of work to be done. We’re looking to get a building of our own to help us spread the gospel. The gospel is the good news about Jesus Christ, the burden removing, yoke destroying, miracle working power of God. The gospel is the good news that Jesus Christ has been anointed with this power. That’s revelation knowledge. And that’s why I’m striving that this CD is played everywhere. It’s going to make people aware.

I found out that this CD is universal. Chinese people like it. It’s really rhythm and blues music, but it’s gospel lyrics. There’s a message in there. I’m singing what a lot of other artists don’t sing because I’m a minister. The lyrics are from the scripture. And experience. I write about my life. If this can work it will bring a new trend to gospel. The music has an r&b spirit, the lyrics have gospel, and they fit like a hand in a glove. Linda Hopkins, she’s using one of the songs from the CD. Barry Marshall says she loves it. It’s called “Witness.” She uses it to close her show. So I’m excited. I feel like I finally got a record that is easy for people to relate to. It brings joy. And I want to make people happy.