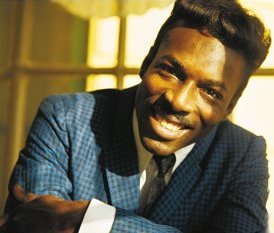

Wilson Pickett (1999)

“We didn’t go in there bullcrapping around. We meant business.” – Wilson Pickett

Pop quiz: Name the top three greats of sixties soul.

If you answer James Brown, Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding, you won’t get much of an argument from anyone.

But who comes next on the list?

Original Interview Audio:

If you say Sam and Dave, I would not disagree. If you say Wilson Pickett, well, that may be an even better answer (and without a doubt Pickett’s name is far better known than those of Sam Moore and Dave Prater).

Yet despite his lofty place in the firmament of soul, Pickett’s life and music are far less celebrated than that of JB, Aretha and Otis. Not without reason. Pickett slogged through the last three decades-plus of his career without a hit, releasing a few scattered albums to little notice.

The one exception arrived in 1999 when “It’s Getting Harder,” his first new release in 12 years, came out on Rounder Records’ Bullseye Blues & Jazz imprint. The critics dug it. Pickett’s commanding voice and hair-raising scream were largely intact and he sounded into it. In a spate of interviews at the time, including this one, the Wicked Pickett, counter to his volatile reputation, came off as friendly and upbeat, even if he also betrayed an old pro’s wary skepticism as to whether this shot at a late-career comeback would pay off.

Tony Fletcher’s new biography, “In the Midnight Hour: The Life and Soul of Wilson Pickett,” puts this moment in Pickett’s latter day career in context. The book is the fullest account of Pickett’s life and music we are likely to get. Alas, it is not a triumphant story. There is no redemption. Pickett, like his peer James Brown, fought his way up from a childhood of dire poverty in the South to achieve enormous professional success, but without acquiring the ability to fully savor it. Unlike Brown, however, Pickett showed no interest in using his status to further civil rights or any other social movement. He wanted hit records and the material rewards they brought him: flashy cars, fancy clothes, big homes. When the hits stopped coming, Pickett became increasingly frustrated and the last half of his life devolved into a sad tale of alcoholism, cocaine abuse and violence against women.

I spoke to the then-58-year-old Pickett on the day of the release of “It’s Harder Now.” In the months that followed, he seemed on track to claim the throne of king of old school soul with his first Grammy nomination (for Best Traditional R&B Vocal Performance, which he would lose to Barry White), a socko performance on “Late Night with David Letterman,” and a duet with Bruce Springsteen at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony (nine years after Pickett failed to show up for his own induction). He still seemed to be gaining momentum later that spring when I saw him steal the show at the W.C. Handy Blues Awards in Memphis, where he won all three categories he was nominated in: Soul/Blues Artist of the Year, Soul/Blues Album of the Year and Comeback Album of the Year. Rounder’s plan to market Pickett to baby boomer blues fans appeared to be working, although an attempt to score a hit single by release an “urban radio remix” of the song “What’s Under That Dress” went nowhere.

But Pickett proved his own worst enemy. “Failing to understand the nature of modern promotion,” Tony Fletcher writes, “Pickett refused to tour nationally behind “It’s Harder Now.” He feared that if he took a lower fee to tour and the record didn’t sell, he’d never get his price back up again.” When sales of the album flagged, Pickett lost interest in it and Rounder lost interest in him. His comeback was over and done.

September 14, 2000

By phone from Pickett’s home in Ashburn, Virginia.

I understand that hurricane Floyd is hitting Virginia right about now. How’s everything where you are?

We live 200 miles from the Atlantic coast so we’re getting the wind and rain, the after-effect of the hurricane. Now it’s headed your way.

How long have you been living in Virginia?

We’ve been here for a year and a half. I lived in [Englewood] New Jersey for 30 years. That was long enough. Make a change. I wanted some space, y’know. It’s too crowded up there and a whole lot of crime. That’s everywhere, But not like New Jersey. It’s a very dangerous place to live. [Pickett did not mention his personal contribution to New Jersey’s crime statistics. In 1991, he was arrested on drunk driving and weapons charges after driving his car across the lawn of his neighbor, Donald Aronson, the mayor of Englewood, and threatening to kill him. In 1992, he was arrested for assaulting Jean Cusseaux, his live-in girlfriend of 10 years. Nine days later, he was arrested again for drunk driving after hitting an 86-year-old pedestrian, Pepe Ruiz, which resulted in Pickett spending most of 1994 in the Bergen County (New Jersey) Jail (where he would suffer an eye injury in a scuffle with a fellow inmate). In 1996, Elizabeth Trapp was found partially clothed and bleeding after running out of Pickett’s house. She told police Pickett had beat her and he was arrested for possession of cocaine after police raided his home, leading to a second stint in the Bergen County Jail.]

So you like it in Virginia?

I’m in the country. I bought a new home down here. But I don’t live in the woods, just in the country. There’s a lot of space and you can breathe.

It’s been a while since your last record. Have you been wanting to make a record for last 12 years? [“It’s Harder Now” was Pickett’s first release since “American Soul Man” on Motown in 1987.]

It wasn’t that I couldn’t make a record. Just before I took a break and retired from the business for 12, 15 years, I got very bored with it. I was making albums. I made two or three with money from my own pocket. I could never get those records done, couldn’t get a good deal with a record company, couldn’t get them played. I got very depressed. But the whole system was changing, including the format of the radio. There was a lot going on I don’t understand even today. So I just got tired of beating my brains out and using my money up. And I wasn’t getting that money back. So I decided, well, if this doesn’t shape up I’m going to call it a day. I got very bored with it. I know that’s bad to say, because I had a very nice career. But now I got bored and had to come back. So there are two sets of boredom there. I hope this time it’s for something good.

So you got the itch to perform again?

I figured that my head is clear, that’s number one. I can do this now without any hangups. I moved. I got peace of mind. I want to try this business again. And R&B has made a great comeback. The older acts are making it pretty good – Aretha Franklin, Tina Turner, they’re out there. Why shouldn’t I be? If you make the effort, make it right, make it good, and let them know you mean it, then they have to take over from there. I think Rounder is a pretty good record company. I like the product we handed them, me and [‘It’s Harder Now” producer/ guitarist/co-writer] Jon Tiven. It’s just that it’s going to take a lot of promotion and effort with this thing to get it moving.

How did you connect to Rounder?

Let me tell you something. There was months and months I thought there wasn’t no Rounder. I thought Rounder was a computer [laughs]. I signed with Rounder through the mail and on the telephone. When Jon Tiven and I had five or six record companies interested, I flew up to New York City and sat with the different record companies and told them what we had in mind. They listened to the product and liked it. None of them came up with anything, but we got a few bites from Rounder. But I said, “There is no Rounder! There are no people there! Rounder is a computer.” Up until a month ago, in Denver, Colorado, was the first time I saw a Rounder person. I said, “Oh, my god. It can’t be! A Rounder person!” So he laughed. I said, “What kind of record company is it where you don’t see any personnel?”

Did you pay for the recording yourself?

The money came directly out of my pocket. I took another shot. Jon Tiven and I, along with Sally Tiven [and keyboardist] Sky Williams, we worked hard writing songs. Then we searched through material and came up with stuff written by Dan Penn and some others. Then I said, “I think we’re ready to cut. I really do. We get in the studio and mean business and I think we’ll come out with a good record.” And I think we did.

Were you trying for that classic Wilson Pickett soul sound?

What I had in mind was not to go that hard. That was my reason for cutting it in New York City and not go down to Muscle Shoals or the Jimmy Johnson studio or Rick Hall’s [Fame] studio or letting [Steve] Cropper do it. I’m saying I wanted to get away from that hard sound, the horns, the hard soul. We lightened it up a little using New York drummers, some young dudes [Todd “Snare” Lowther and Simon Kirke of Free and Bad Company renown, a not-so-young 50 at the time]. And we came up with a very unique sound. We kept having musicians come into the studio at night and we’d go through stuff. We had this harmonica player [Mason Casey] walk in off the street, pull up a chair and start blowing while I’m busy putting a vocal on. Jon comes to me and says, “I want you to hear this.” And he had sneaked in there and put the harp on there. I said, “Shit, man, that sounds good.” So we use him, just like that. And this is the way Jon and I were doing things. A certain amount had to be planned to get to the real nitty gritty, but a lot of it was sheer luck. A lot of people said, “Well, if I can play with Wilson Pickett, shit, that makes me feel good.”

What was your approach to writing songs with Jon Tiven? Did you do it the same way you wrote “Midnight Hour” with Steve Cropper?

No, I had never wrote anything with Jon Tiven. I didn’t even know Jon Tiven. We knew what we had to do. I put out the word that I was looking for a producer because I wanted to go back to the studio. Jon Tiven started sending me a whole lot of demos and stuff [most notably an advance copy of “This What I Do,” an album Tiven produced for Pickett’s old Falcons bandmate and longtime friend Sir Mack Rice, writer of “Mustang Sally”]. There were a couple of songs there that made me think I should come up there [New York City] and go over them. So I flew up there. And that was when I realized that I could work with Jon Tiven. We got along great. Although it was my money, it was his effort. Which is equally important. But we were both in there to come out with a marketable product. We didn’t go in there bullcrapping around. We meant business.

The title, “It’s Harder Now,” could be interpreted in different ways. In your mind, what does it mean?

It’s not talking about it’s harder to get in the business anymore. If anyone listens to the record, I’m singing about a girl. And I’m talking about people, how it used to be easy to mess up my mind, but it’s harder now. It used to be easy to take up my time. I used to be an open book and anyone could have a look, y’see. So it’s not talking about getting back in the business as a lot of people who don’t listen good think. They figure I’m saying it’s harder now to go into music. It’s not about that.

You’ve got a few songs on the record [“What’s Under That Dress,” “Taxi Love,” “All About Sex”] where the lyrics go in a pretty raunchy direction.

I think that if you don’t, chances are you ain’t gonna sell. Years ago I would never do a song called “What’s Underneath [sic] That Dress?” But here I am writing a song with Jon Tiven and Sally Tiven and it’s talking about what’s underneath a woman’s dress there! We were up in Colorado and I decided I would do that song. It went over tremendously. And two girls lifted their dresses up! I looked around at the band and said, “Hey, they’re really taking this seriously!”

You’re been known for many years as the Wicked Pickett. Were you wicked to start with or did you get the name and then try to live up to it?

I had to live up to the name after I got it. I’ve told how Noreen Woods named me that, an Atlantic Records secretary. Because she caught me pinching one of the other secretaries on the butt one morning, when they had the short dresses. She said, “My, you sure are wicked.” Jerry Wexler was sitting in his office and heard her and came running out. “That’s it. That’s the title of your next record!” And that’s how I got it. So now when people took it another way, I had to live up to it. It bothered me for a long time, I have to tell you that. But right now it doesn’t bother me.

So now that you’ve gotten this new record out, do you think you’ll do more recording?

Right now I negotiated a deal for three years with Rounder. If we do well, we go further. But we’re going to do more products and do more stuff.

[After the disappointing sales of “It’s Harder Now,” Pickett considered making a gospel record or an all-star duets set, but none of his plans to return to the studio came to fruition. He died on January 19, 2006 from a heart attack. He was 64 years old.]

[Performing in Ghana, 1971]