“One of my first public appearances was at a talent contest. I sang and played Fats Waller’s ‘fododo-de-yacka-saki want some seafood mama.’ I could just see the teacher saying, “This boy is going straight to hell.”

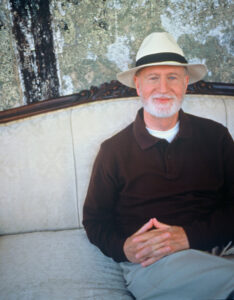

Wondering what Mose Allison was up to lately, I checked his website – even soon-to-be 88-year-old jazz/blues singers have websites – and discovered two things.

First, if you’ve never seen Mose live, sorry, you’re out of luck. “Under the heading “Upcoming Tour Dates,” it reads: “After 65 years of touring Mose Allison has retired from live performance.”

The second bit of news was the September, 2015 release of the first new Mose Allison recording in five years, a live CD titled “American Legend” (I’d bet all my Charley Patton records that the self-deprecating Mose was not the one who chose that self-aggrandizing title. Definitely not his style). I haven’t heard most of “American Legend,” but the six samples on the website are enough to prove that Mose’s voice, piano chops and sense of humor were well-intact at the time of its recording in 2006.

At the time I spoke with Mose, the hard-touring 66-year-old was headed to Boston for a two night stand at Scullers Jazz Club on August 12 and 13, 1994. He was enjoying – warily, to hear him talk about it – an unexpected flurry of attention due to the coincidental release of his new Blue Note album, “The Earth Wants You,” at the same time as the appearance of a Rhino Records retrospective (“Allison Wonderland”), a three-CD box of ‘60s Columbia LPs (“Hijinks!”) and the re-release of two early ‘80s comeback albums, recorded after an unplanned hiatus from the studio during the disco era.

Mose kept on writing and recording genius originals through the ‘90s. And after a quiet ’00s, he shimmered back again in 2010 with the Joe Henry-produced “The Way of the World” on Anti-, which proved that Mose’s special brand of song was as fresh as ever.

Now, with his retirement from live performing and, presumably, the recording studio, we can only wonder why he hasn’t been honored by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Grammys and why no president has hung one of those National Medal of Arts around his neck.

It’s not too late. Mose was and is a national treasure.

August, 1994

From his home in Smithtown, Long Island. by phone

What happened that all of a sudden there are all these releases of your music?

It’s a little unbelievable. I usually have about one CD every three years and now all of a sudden I’ve got about 10. I can’t really explain it. I think everybody thought I was dead. I have no idea. I got these calls one at a time. First I got a call from Rhino saying they were doing a retrospective [“Allison Wonderland”]. Then I got a call from Warner Brothers saying they were putting out these Elektra Musician things [“Middle Class White Boy” and “Lessons in Living,” both originally released in 1982 on Discovery Records]. Then I got a call from Sony and it just kept happening. I couldn’t figure it out. I still can’t. I don’t know whether it’s good or bad.

What could be bad?

Well, I’m just waiting for the reaction. Somebody’s bound to say, all these Mose Allison records are coming out, what good is he? I always say when you get a real fan you get two enemies. The only thing I’ve noticed is more requests for interviews. That’s the only thing so far. I’m just waiting to see if it makes it easier to work, that’s my main thing. I’m doing 125 nights a year more or less. That’s about right. As long as I can maintain that, I’m happy.

A hundred and twenty-five gig a year sounds like a lot.

Well, that’s just sort of what it settled into. A few years back I was doing more, but there were a lot of one-nighters. So I found I wasn’t really making money, I was just traveling a lot. The money was going to expenses. So now I’m doing less one-nighters, mostly weekends and three-nighters. There are a few six-night gigs, but not many.

[Mose reflects in song on his career in show biz in this 1989 performance.]

And you have a new Blue Note album [“The Earth Wants You”]. Was the thought to put it out now and try to catch a wave of interest in your work?

It was just their schedule and they stuck to it. It all happened to hit around the same time.

Are you gratified by your older material re-appearing? Is there a sense of satisfaction in knowing your work stands up?

There is some, but some of it I’d just as soon not hear [laughs]. But it’s nice for it to come out. It makes you feel that someone thinks it’s worthwhile. Also, on the Sony thing, they’ve got three instrumentals that had never been released. One of them I had completely forgotten about. I was amazed. I felt sure I had never recorded “Am I Blue.” I thought it was a mistake. I had to listen to it and I found it actually was me. I’m glad they put out those things, “The “Hills” and “High Jinks,” I like both of those. [He is referring to previously unreleased original tracks that appear on “High Jinks!,” a boxed set of three early ‘60s LPs, “Transfiguration of Hiram Brown,” “I Love the Life I Live” and “V-8 Ford Blues” released on Sony’s Columbia/Legacy imprint.]

Are you kidding when you say there’s some stuff of yours you’d rather not hear? You really don’t like some things?

No, I’m not kidding. I feel that way about the new record. I feel that way about all my records. There are spots I like and spots I don’t like. ‘Cause I’ve never had any time to do records. Any record I’ve ever made was done in three sessions, four tops. That means you have to do 12 tracks, sometimes more, in 12 hours. Since you’re sometimes doing new tunes you’ve never done on the job, there are stretches where you hear something and you think, “Oh, man, why didn’t I think that over more?” Or “Why didn’t I concentrate more?” There’s always places you feel reluctant about. But hopefully there are a few places you feel good about. It balances out.

When you hear you old recordings and compare them to your new material – do you think you’ve gotten better over the years?

Not really. I just feel like it’s a different me. It’s a different world. It reminds me of what was going on in that period. Those albums transport me back to the time they were recorded, which is completely different from now, that’s for sure. A lot has happened in 35 years.

Your music is described as a mix of blues and jazz. Did you start off favoring one more than the other?

They sort of came up together. Unlikely enough, I had a cousin who was a jazz fan and she had some jazz records. Remember, this is before they had electricity there in Tippo [Mississippi]. We had a little wind up victrola and she had some records by Count Basie and Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong. So I started early listening to those things. They got electricity down there by the time I was about 12 and then they got jukeboxes in some of the stores. The Tippo service station had a jukebox. It was about 60 percent country blues and 20 percent big band swing and 20 percent country music, what they called hillbilly music at the time. So I got to hear it all. Of course Louis Jordan and the Tympani Five were always on the jukebox. I liked him a lot when I was young. My first attempt to write songs were pretty much in the Louis Jordan vein.

Growing up in Mississippi, did you have a lot of exposure to the blues?

Not a lot. I had exposure to where the blues came from. The field workers. The pace. The speech. And there were some singers around. There was the local black church. And now and then a guitar player would come through. So there was some of that. But mostly I heard blues on records, people like Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Minnie, Tampa Red and those kind of things.

Was there any stigma attached to being a white boy listening to blues?

No one ever said a word to me the whole time I lived in the South. It never occurred to me I was doing something that someone might disapprove of until I got to New York [laughs]. Then some of the [music] writers made me aware of that right away. Here’s a white Mississippi college boy singing the blues. Then I got to thinking, well, maybe something’s wrong [laughs].

When did you start playing professionally? Do you remember your first gig?

My first professional gig was in a roadhouse called the Rising Son, which was outside Greenwood, Mississippi on the highway. I played a weekend there with some older guys from the Ole Miss college band. I knew one of the guys and they hired me. I played trumpet. This was my first nightclub experience and I was thrilled to be playing with these older musicians. I must have been about 15 or 16. Now my first professional six-night gig was in 1950 in a roadhouse outside Lake Charles, Louisiana. That was with a trio. That was the start of my professional career.

Were you singing at that time?

Oh yeah, I was singing. I always sang. I wrote songs in grade school. In fact, one of my first public appearances was at a talent contest. I sang and played Fats Waller’s “fododo-de-yacka-saki want some seafood mama.” I could just see the teacher saying, “This boy is going straight to hell.” That was a Fats Waller tune called “Hold Tight.” I was about 14 and played that in the assembly hall in the high school.

What’s your take on what you do? Do you consider yourself a jazz musician or a blues musician?

I don’t think they’re opposed. To me, they come from the same place. This stuff has been called so many different things – ragtime, swing, dixieland, bebop – just permutations of it – is that the right word? It all comes from a similar source. I don’t see much of a conflict myself. Although I am a jazz pianist. And I wouldn’t call myself a blues singer in the classic sense like Muddy Waters or John Lee Hooker or Lightnin’ Hopkins or those guys. I don’t just play blues. My vocal and songwriting thing is based on blues, but it really isn’t blues. I haven’t written many 12-bar blues.

When you moved to New York City in the ‘50s, you played with people like Zoot Sims and Al Cohn. Was your ambition to have a career as a jazzman?

I considered myself a jazzman. I had always sung on gigs down south before I moved to New York, so I assumed singing would be part of it as well. What I wanted to do was get somewhere where I could make a living. I was getting by hand to mouth down South. I would go to a town like Dallas or Jackson, Mississippi….I saw that I couldn’t spend my life doing that. At that time, we’re talking mid-’50s, that was the beginning of the jazz boom. It was being taken seriously for the first time and they put Dave Brubeck on the cover of Time. I just figured there was a lot happening, so I went there [to NYC] thinking I could get better jobs. That was the main thing. But I was mostly interested in jazz players and that’s who I hung out with. So that’s how I got the gigs with Zoot and Al.

But as it turned out, you ended up being more influential among rock musicians than among jazz players.

Well, the jazz thing went into a different direction entirely. It went into complexity and pyrotechnics, where I’d been going back to simplicity all the time. My songs are all simple songs. I wrote a satirical song about it, “Long Song.” It’s on the [1990] album “My Backyard.” [“What this show needs is a long song, a real blockbuster King Kong song, a song with lots of different sections, with melodies drifting off in all directions.”] I haven’t tried to write complex songs with very involved lyrics. I’m trying to keep it down to easily accessible stuff and put some truth in it and a little irony most of the time. I see them as sort of basic chants rather than very sophisticated songwriting. The jazz thing is into virtuosity. My songs don’t appeal to those people. [Here Allison mentioned a jazz group from Montreal, Jim Hillman and the Merlin Factor, that recently had covered his “Hello There, Universe” – the title cut of one of his least known albums – and he loved it.]

You had a very active recording career when you started out but then in the ‘70s you hardly did any recording at all. Was that a low point for you?

Oh, right. I was with Atlantic and we were at a stalemate. They wanted me to do something more commercial and I didn’t want to do the things they suggested. They wanted me to go down to Muscle Shoals and stuff like that. They even sent one of their lackeys around to suggest to me that I do a disco album [laughs]. We were sort of sitting each other out. It didn’t matter to me. I was working regularly. I never made much money from records, I only made money from the songs. I made my living working in clubs.

[Mose Allison Trio on PBS’s Soundstage, 1975. With Jack Hannah – bass and Jerry Granelli – drums.]

On the new album you’re working with guys like John Scofield and Joe Lovano. Did you and [producer] Ben Sidran set out to choose young players to work with?

We got together. It’s a get-together type thing. He’d suggest somebody and I’d say yes or no. Then I’d suggest somebody and we went at it like that .

You also have an old hand in [drummer] Paul Motian.

Yeah, that was great, man. Paul is one of my favorite people in the world. We played together with Stan Getz, with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, and he played my first trio gig in New York that I played at the Cafe Bohemia in 1958 with Addison Palmer on bass.

Looking back at your career and listening to all the music that’s coming out on these retrospectives, it’s really clear that you’re music has stood the test of time. Does this surprise you at all?

Sometimes someone will ask me for a sheet on a song – you know nothing’s published. So I’ll go down in my basement and look at my sheets and I’m a little bit proud that I’ve got a pile of sheets there. The songs are still pertinent, at least most of them. Some people think they’re worthwhile. It’s a nice feeling. But you can’t rely on that [laughs], you can’t rest. I’m still trying to play. My main thing has been the performance. Right now, as I said, there are very few six-night rooms left. The whole trend is for people to stay home with all those machines. It’s really bad for nightclubs. I don’t know what’s going to happen to nightclubs. One of my favorite places just closed, the Vine Street Bar and Grill in L.A. I’d been playing there two or three times a year for 15 years. I used to work three weeks a year in Boston, now I do one weekend a year. It’s tougher to find clubs. Someone has to come up with some concept that’s gonna reinvigorate the nightclub business. I don’t know what it’s going to be, but I’m hoping it’s going to happen. I just got an offer to play in a museum [laughs].

I read that in your youth you had literary aspirations. Do you think you’re ever going to write a book?

That was just after college when I’d taken creative writing and aesthetics and philosophy and all that [Allison graduated from LSU in 1952 with a BA in English]. Since I started playing – I went right to work in clubs. As long as I’m playing I’ll probably never do anything like that. But if something happened and I wasn’t busy, it might be something to fall back on. I read a lot. I’ve never really known how I wanted to approach a book, whether to do fiction, a confessional or what. But if it comes to it, I’ll find an approach and a voice for it.

[On 2010’s “The Way of the World,” Mose turned Willie Dixon’s “My Babe” into “My Brain.” ]