Merle Haggard (1999)

“…you’ve got these perfect people performing perfect music and it’s perfectly boring to me.”

At the end of the 1990s, Merle Haggard was one disgruntled country music legend. He was enduring the worst stretch of his career, his “lost decade.” After topping the country charts a remarkable 38 times between 1966 and 1987, the hits had stopped coming. He switched labels from Epic to Curb in 1990, but the deal turned toxic. In 1999, “the working man’s poet” was 62 years old and working as hard as ever, touring by bus and playing an endless string of one-nighters, including an April 18 stop at the Lowell Memorial Auditorium during one of his infrequent swings through New England.

Haggard had plenty to gripe about when we spoke and he did not hold back. Yet he sounded more wounded than angry: a noble outsider disappointed and hurt by the ways of the world, though not surprised by them.

A weekday morning, the second week of April, 1999

By phone from his home in Palo Cedro, California

Are you at home in Palo Cedro?

You got the old Mexican drawl there [laughs].

You haven’t put out a new album in what seems an unusually long time for you. Do you have something in the works?

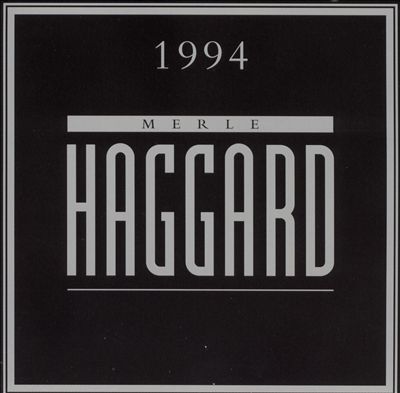

That’s good to know that somebody’s interested enough to notice. Yes, I do. We were under a contract to Curb and we got into a dispute, he and I. He [Mike Curb] wouldn’t put my records out actually, is what it was. [Haggard claimed that Curb illegally had taken control of Haggard’s back catalog.] And he just took a vindictive attitude and shut me down for several years. I had a couple of records [“1994” and “1996”], but they didn’t have any covers on them. They look like tombstones.

Since that time, when I realized he wasn’t going to do anything with my product, I just kinda went over in the corner and sat down and waited for my contract to be up. Now that it is up I had to cut some records that I felt were good enough to re-launch my career, I guess you could say. We’re in the process of doing that. I’ve done three projects. In fact. we’re in the midst of a gospel music project. [The 2001 album “Cabin in the Hills.”] There are some new things I’m doing, and we’re also re-releasing all the gospel music I’ve done over the years. I’m gonna do a new box set of that sort. [The gospel box has not yet appeared, at least as far as I can see after searching discographies listing many dozens of Haggard compilations.] And then I have a situation where we’re going to do 61 remakes – which we’ve already done. They’re going to come out on RCA in conjunction with a pay-per-view program that may be as much as three different evenings from Las Vegas, just like a big fight. And RCA plans to have those records in the bins all over the world and do a million dollars worth of advertising. So you’re going to be hearing a lot about me, at least more than you have for awhile. [Haggard’s next official release did not arrive until 2000, “If I Could Only Fly” on the indie label Anti-.] We have 61 songs to perform, 56 of them being hits from the past that we’ve re-recorded, including things like “Poncho and Lefty,” things we deemed to be the best. I was fortunate during my hot period. I had 63 Top Two songs. A lot of them were Number Ones. I think Conway [Twitty] had a couple of more than I did and there’s a couple of other people in the same bracket. But nobody had 63 Number Twos. [The 61 songs project also appears to have fallen through.]

CBS has done the unforgivable. They lost some of their masters. They came to me and asked if i would make ‘em some new ones, I said, “Yeah, but I sure ain’t gonna give ‘em to ya. It’s gonna cost you a lot of money. I’m just gonna lease ‘em to you this time, I’m gonna keep the safeties.” They lost things like “That’s the Way Loves Go,” “Poncho and Lefty.” I don’t know how in the world a record company loses masters. I’m sure they wouldn’t approach me and offer to pay me to make new ones unless they had in fact lost ‘em. They may be lost between walls of corporations or something. The Japanese bought so much, Columbia Pictures, CBS Records, some big publishing companies, I think they might be in some sort of state of confusion there. They don’t know exactly what they got, who they owe [laughs]. We’re auditing them at the current time and I’m gonna be auditing them for the rest of my life on account of this confusion.

I’ve just had a lot of bad luck over the past 10 years in getting product to the public. We fell out of the criteria with our age. Everybody probably thought I wasn’t gonna live this long, but here I am. I’m still here. We still have crowds when we perform and I still got the best band in the country. Me included don’t know what to think about it.

Do you feel alienated from what’s going on in country music today, with all the hat acts and such?

Yeah, and I’m sure glad [laughs]. They don’t play us on the radio, What they call the New Country. Let me be clear not to put down that sort of thing. Hey, if it works, more power to ‘em. But it’s not my bag. I don’t understand what they’re doing. I know everything’s in tune, but I can’t hear no melodies. It’s not anything for me to criticize. We had so many good years of airplay – and they still play a Merle Haggard classic at times on the FM side, so there’s nothing for me to do but be thankful. And I think if I were to grab a phenomenal song or something that I could make ‘em play me.

If you think back historically with the performing arts, plays, films, music, if [ageism] had been the rule the amount of talent the public would have missed would have been enormous. Some people, musicians and singers especially –I mean Pavarotti is exactly the same age I am. There’s nobody knocking him out of the saddle. [Luciano Pavarotti was born 18 months before Haggard, who was perhaps feeling his age: he’d turned 59 on April 6, shortly before this interview.]

This music they’re making is for videos. I think that’s what happened. The music is secondary. It’s somewhat of a mini soap opera taking place. So you’ve got these perfect people performing perfect music and it’s perfectly boring to me. If there’s anything I hate it’s perfection. Perfect has gotta be the worst thing of all when you’re watching someone perform. Y’know, the guy who rides his bicycle across the high wire, if he don’t almost fall it’s really boring. Music just seems like it’s so refined, so perfect. Everybody is using the same damn band. So I quit listening about 10 yrs ago. I still listen to the same old records I used to when I was a kid. And I’ll be damned, I believe that Elvis is still the king [chuckles].

[Merle Haggard live in Las Vegas, 1999; skip to 3:00 for one of those charming, less-than-perfect moments.]

It’s kind of ironic that all these soundalike male country singers that have supplanted you on radio so obviously try to sound like Merle Haggard.

It’s absolutely the truth. Everytime I see one of ‘em, meet one of ‘em, I’m as cordial and respectful as I can be. I don’t think they’re in control. I don’t think these people that studied me and Willie and George and Lefty and Cash, I don’t think they’re able to produce their own music. I think their hands are cuffed. Whereas when Johnny Cash walked into the studio – or walks in still yet – he’ll be in charge. I don’t think that’s the case with some of these new kids. If you turn one of them loose you might find a Hank Williams or a Waylon Jennings if somebody let ‘em be themselves. Let ‘em try their own band. But they come to town down there and first thing they do is say, “Hey, you can’t use your own band. We don’t need those guys. Send ‘em home, break their hearts and all that because we’ve got a session set up with The A Team.” I think that’s what’s going on. Because the bottom line is money and there are people who believe that they can create and clone a Hank Williams. And that’s what we got, it’s not only in music, it’s in films too. What else have we had except “Titanic”? And “The River Runs Through It,” thats’ a great film, Robert Redford. But with the amount of films that are going on you’d think you’d see a John Wayne walk out of that. Or that there’d be a Hank Williams coming along here. But I don’t see none.

You’re at a stage in your career where you get lots of honors and awards, but it’s almost as if they’d rather praise you than play you on the radio.

It’s a double-edged sword. That was the reason Mike Curb kept me on his label for 10 years – for my name. But he wouldn’t let my music be heard. I don’t care if you print this. It’s the truth. Any way they can find to exploit Merle Haggard in this business, they do it. We do TV shows. We’re not short of work. We’re in demand, but…there are some honest roses coming my way, hero worship and all that, I’d be a fool not to see it. All I can do there is try to honor it, say the right things.

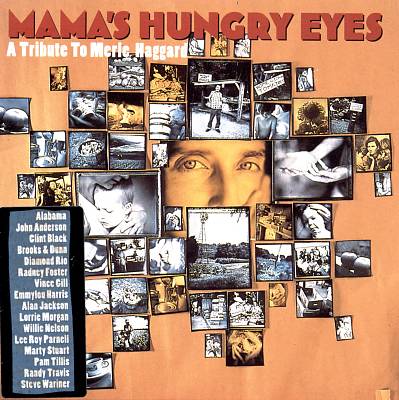

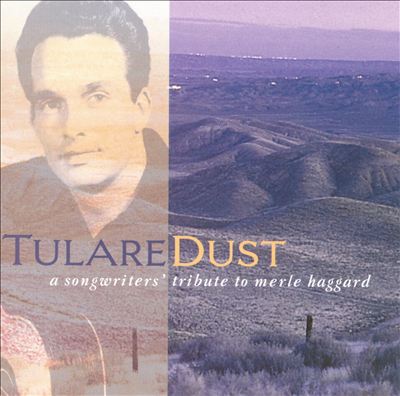

A few years ago [in 1994] you were the subject of two very different tribute albums that came out almost at the same time. What did you think of them?

Some were outlaws and some were conformists. One album [“Tulare Dust”] was an outlaw album and one album [“Mama’s Hungry Eyes”] was a publisher’s promotion [laughs]. On one, the love showed through. The other one, there was a lot of that too, but there again their hands were cuffed and they couldn’t do it the way they wanted to, they had to do it according to the producers’ directions. If there’s anything I find unnecessary in this business it’s a musical producer. If a guy that’s singing a song doesn’t know how to run his own session than maybe he ought to go back to selling cars. Producers are helpers. They ought to be working under the man whose name is on the record in big print. They ought to be settin’ there saying, “What can I do?,” watching for people playing out of tune, keeping people from runnin’ up your back. But I don’t think they ought to be telling people…

It’s strange. A guy walks in with a talent, a guitar and songs he’s written, and here’s a guy who used to be a drummer who’s never written a song in his life, James Stroud, sitting there because of who he knew, telling this guy with some talent how to make a record. So you wind up getting the same thing every time. And James Stroud is a friend of mine, I don’t have nothing against him. He’s just the first name that came to mind. But that’s what you have going on down there.

You got young guys like Hank Williams [III], you know they’re around, goddang, you know there’s enough things to write about, there’s enough horrifying subjects to come up with. But they won’t play ‘em on this format they got nowadays. If you write about anything off of the mainstream, thin subject matter they got going, they won’t play it. They’re afraid that people will look up from their computers. I’ve had people who are in charge of as many as 300 stations, the program director told me that. My God. That’s the opposite of the way I was brought up. I don’t understand that way of thinking. I thought music was meant to tease the emotions.

Did the outlaw tribute give you some hope for the future?

I heard it from the grapevine, I don’t know if it’s true, but that there are some real changes happening right now in New York, L.A. and Nashville. That this stuff we’re talking about is all of a sudden not doing it no more. They’re looking in all directions for answers. I think we’re going to see something that’s going to be more honest, more diverse. America is great at limiting diversity. We’ve only got two kinds of cows, red cows and black cows. Red chickens and white chickens. You go to Australia, they got all different kinds of cows and chickens. America seems to want everything to be in a category, in a box. They wanna put you in a little box so they can pull you up on the computer easy. If you don’t fit in….you’ve got to market things that way. Everything’s got to be boxed and properly stored or they won’t buy it. That’s what we’re trying to do now to market all this music. I’ve got a lot of music to let go of the right way. I’ve got to make all the decisions because I don’t trust anybody out there no more. I’ve got a couple of good attorneys and that’s it.

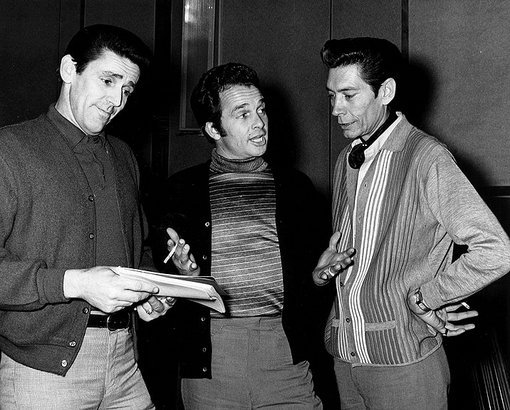

[Fuzzy Owen, Merle Haggard and Lewis Talley. Owen, who would become Haggard’s longtime manager, helped pioneer the Bakersfield Sound with his cousin, Talley. They started Tally Records and recorded Haggard’s first sides in 1962.]

I’ve read that you were planning to revive the Tally label. Is that going to happen? [Haggard recorded his first hits for Bakersfield-based Tally in the early ‘60s.]

Well, I was going to do that, but there are a couple of grandkids sitting out there like frogs on a log waiting for me to do that so they can sue me. You understand? Lewis Talley [whose surname, in distinction to the label name, was spelled with an “e”] had grandkids, so I can’t do that. So I have a new label, In Orbit, which is my own label. But I’ve got this deal with RCA, and a deal for the gospel music with people who are more familiar with selling records than I am. I’d rather let them do it than become a Garth Brooks, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to run record companies or anything like that. [In Orbit appears to have existed only briefly, when Haggard recorded guitarist and longtime friend Freddy Powers in the early 2000s, though the resulting albums did not end up as In Orbit releases.]

Are you still touring as much as ever or are you starting to slow down?

Every year we talk about slowing down, but it never seems to happen. I have a wife [Theresa] sitting here, her question is why are we doing this? I don’t really know. I guess it’s what I do. I have a beautiful family, a young family, a six-year-old and a nine-year-old. I think I’m gonna homeschool ‘em for the next couple of years and take them with me. Maybe by then I’ll be too old to do it, but some way or another it seems like it would be sinful not to use what God’s given me as long as I’m able.

Do you enjoy the travel or is it only the playing that makes it worthwhile?

I’d rather do anything then climb in the back of the bus. But you’re right, once we make it to the bandstand, I get on the bandstand, I’m safe then. It’s a great experience to be in the midst of that music, that good band, and have the love of the audience. The respect is obvious. It’s a wonderful place to be, the bandstand for me, that’s what makes it all worthwhile. Y’know, we don’t make a lot of money. We’ve got enormous costs. But we make a living. We spend our life on the highway. Here I am with a second family and I’m talking about taking them on the road with me so I can see my wife and see my kids grow up.

I imagine you have a lot of pride in having the Strangers with you, one of the greatest bands ever.

Oh yeah, that’s what I’m talking about. That’s what makes the bandstand so inviting. To stand there with these guys that have taken a lifetime to locate. They draw each other. It’s kind of like the Yankees, they don’t draw any bad ball players. The Stangers, if you happen to hire a guy by mistake that’s incapable or something, they’ll eliminate him for you. He’ll quit, because the fire will get too hot. It’s not only a good band, it’s a band with all kinds of experience, that can change in the middle of a stream. Y’know, I don’t do any set sort of a show, it’s off the cuff. That’s the way the guys are capable of playing. We might stop in the middle of a song. I might start a song they’ve never heard. It won’t be long before they’re playing it right. The audience enjoys that. It’s so different from the television and the music you’re hearing nowadays. Our response has been tremendous. People really appreciate it. They’re not stupid. They miss [this kind of music] and they crave it. Our tickets sales are proof. The age diversity is incredible. I walked off the bus and there was a black couple standing outside the bus. They had a little girl, her daddy holding her. This little girl said, “Is that the man that sings ‘Big City?’ What it showed me was just how powerful music is. That child didn’t know who I was, didn’t even ask my name. I walked over and they said, “We’re here because she chose your tape. That’s why we brought her.”

[“The Bottle Let Me Down,” live, 1968: Merle Haggard and the Strangers, with Norman Hamlet on steel guitar and Roy Nichols on guitar]