When I heard that Johnny Winter had died on Wednesday, I flashed back to the first time I heard him play. But then whenever I thought of Johnny Winter, I thought back to that night – December 13, 1968 – which I am sure was just as memorable and far more significant to him.

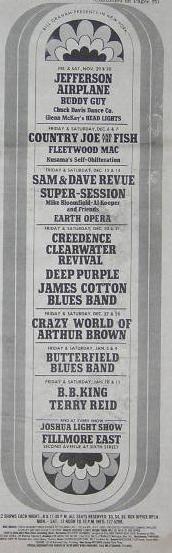

It was a Friday, two weeks after my 20th birthday. I’d started playing bass about a year-and-a-half before, rock and blues. More recently, I’d fallen deeply in love with soul music, Otis Redding, above all. Otis had died almost exactly one year before and I regretted that I would never get to see him live. But my other Stax/Volt favorites, Sam & Dave, were playing that night at the Fillmore East, which had opened in February of that year. No way was I going to miss this show.

As I recall, I went by myself, walked up to the box office and bought a ticket, which cost around $4. I sat somewhere in the middle of the orchestra and settled in for the show, a triple bill, like most Fillmore concerts.

The opening act was Earth Opera, a Boston band which starred then-unknowns Peter Rowan and David Grisman. I don’t remember a thing about their set.

The opening act was Earth Opera, a Boston band which starred then-unknowns Peter Rowan and David Grisman. I don’t remember a thing about their set.

But the second act was a different story: Super Session with Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield. At first I was a bummed out that Stephen Stills, who played on the first Super Session album, was not present, but I was still psyched to hear Kooper and Bloomfield. I was a big Kooper fan from his work with the Blues Project. And from the moment I fell in love – hard – with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Bloomfield was one of my guitar favorites. And I had witnessed Kooper and Butterfield on stage together once before at what turned out to be an historic event: Bob Dylan’s 1965 concert in Forest Hills (the one where a riot broke out; but that’s a story for another day).

Not far into the Super Session set, Bloomfield stepped up to the microphone and, as I remember it, told a story about encountering this musician from Texas – “the baddest motherfucker” – the night before at a Manhattan rock club, Steve Paul’s The Scene. And then Bloomfield introduced “Johnny Winters,” adding an S to his name.

A wraith-like figure in black, the better to set off his milk white skin and flowing corn silk hair, walked across the stage. The band went into a blues number. Johnny pulled out a harmonica and started to wail. Absolutely killer.

The next song, B.B. King’s “It’s My Own Fault,” kicked off with a Bloomfield solo. When it was time for the vocal – surprise! – not Kooper, not Bloomfield, but Winter started to sing. Oh. My. God. How was all that sound coming out of this freak’s stick figure body?

And then he picked up a guitar and started to play. You have to imagine the context to appreciate the impact of this audacious unknown. He wasn’t just playing taking a solo, he was daring to follow the great Mike Bloomfield – and more than holding his own. Stunning. Was this skeletal apparition the next blues/rock guitar god?

Well, yes.

The following week, Johnny Winter was signed to a recording contract by some Columbia Records execs who had come to the Fillmore to see Super Session, a Columbia act. The buzz built rapidly from there.

Now here’s where I have to tell you that my memory of how Winter’s performance unfolded that night is (probably) not quite accurate. At least that’s what Al Kooper tells me.

After Kooper moved to Boston I interviewed him several times and we became friends. During a listening session in his Somerville living room one night, Al told me he was producing a recently discovered recording of the Super Session performance at the Fillmore East with Johnny Winter. I excitedly told Al that I was there and shared with him what I believed to be my crystal clear memory of the show.

And he proceeded to tell me that it didn’t go down that way. For one thing, Winter didn’t play any harp. And….well, this was a conversation from eleven or twelve years ago, so I don’t remember the specifics. I argued with Al, but he said he had proof: the tapes of the show, which he was working on editing and restoring, and which were released in 2003 as “Fillmore East: The Lost Concert Tapes 12/13/68.”

Who am I to argue? But I swear Winter blew harp that night. And blew great.

For Winter – and Bloomfield – fans, “The Lost Concert Tapes” is well worth seeking out. Even though, as Kooper explains liner notes, the performance has its musical rough spots, largely due to drummer Johnny Cresci, a jazz player whose style clashed with the other members of the rhythm section, bassist Jerry Jemmott and pianist Paul Harris (Be warned: If you listen to the album on Spotify, the tracks are out of sequence. Cue up Bloomfield’s intro before “It’s My Own Fault.”). Never mind the backup flaws. Bloomfield’s playing is so good that Kooper selected several performances from that night for inclusion on the eye-and-ear-opening, three-CD/one-DVD Bloomfield set he produced this year, “From His Head To His Heart To His Hands.” One of those tracks is a previously unreleased Kooper-Bloomfield original, “Santana Clause,” a prescient tip-of-the-axe to you-know-who.

On that night in ‘68, the Fillmore audience was blown away by Kooper and Bloomfield and especially Johnny Winter, who came riding out of nowhere like an albino vision of a wild west gunslinger. But the show was far from over. Unbelievably, it got even better. Sam & Dave came onstage backed by a huge band featuring two drummers and about a dozen horn players, as if hellbent on blowing away the Fillmore hippies, a far different crowd than their usual audience. And it worked. Sam & Dave’s combination of fiery vocals and exuberant showmanship won over the Fillmore as surely as Otis conquered the Monterey International Pop Festival.

Suffice to say, I got far more than my four dollars worth at the Fillmore. Thank you, Johnny Winter, for that night and all the others.