John Fogerty

“….that big terrible rubber band that was tied tight around my heart loosened up…”

May 19, 1997

By phone from San Francisco

In 2013 John Fogerty released “Wrote A Song for Everyone,” a guest-filled album consisting mostly of covers of classic songs he wrote for Creedence Clearwater Revival. Fogerty does “Fortunate Son” with the Foo Fighter,” “Bad Moon Rising” with the Zac Brown Band, “Who’ll Stop the Rain” with Bob Seger, and….well, you get the idea. It’s far from my favorite Fogerty record, but I’m glad he feels good about digging into the CCR songbook.

For far too many years he didn’t.

“That big terrible rubber band” started tightening around his heart in 1971, when Fogerty’s guitarist brother Tom quit CCR because he was fed up with his younger sibling’s domineering ways. A little more than a year later, the other two members of CCR, drummer Doug Clifford and bassist Stu Cook, decided they, too, had had enough of working with Fogerty and the band broke up. Meanwhile, Fogerty became mired in a dispute with CCR’s label, Fantasy Records. He was so distraught about his business situation that, after releasing two solo albums, he stopped recording and performing in public for a decade. He made his comeback in 1985 with “Centerfield,” a huge success that included two of the most bitter songs you’ll ever hear, “Mr. Greed” and “Vanz Kant Danz,” thinly disguised hate letters aimed at Fantasy’s owner, Saul Zaentz. During this entire period Fogerty would not play any of the CCR songs he had written because the royalties went to Fantasy. When Tom died at age 48 in 1990, the brothers were not speaking to each other. When CCR was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, Fogerty refused to play with his surviving ex-bandmates, Clifford and Cook. Meanwhile, another decade went by between the release of solo albums, 1986’s “Eye of the Zombie” and 1997’s “Blue Moon Swamp.”

I caught up with Fogerty the day “Blue Moon Swamp” hit the store racks. He spoke to me by phone from his hotel in San Francisco a few hours before the second show of a two-night stand at the Fillmore, where he had opened his Blue Moon Swamp World Tour the night before (the tour played Boston’s Harborlights Pavilion on July 20). Notably, Fogerty was performing his CCR songs for the first time in more than 20 years. I was not sure how willing he would be to talk about his troubled career, but Fogerty, whose speaking voice sounded notably higher than expected, was warm, open and eager to talk, if still hurting and defensive.

How did it feel getting back out on stage?

We actually did our first show last night, the first show of the tour, I guess you’d say. It was wonderful. We were well-prepared so I didn’t have any of those kind of concerns…if you don’t know what you’re gonna do, it’s pretty scary [laughs]. Still, everything clicks up a few notches when you’re in front of people, especially when they’re on your side.

Did it make you feel that this is something you should have been doing a long time ago?

I already know that. Yeah. That’s a whole book you could write. It’s very unfair what happened to me, but that’s not what I’m bringing to the stage. Here I am now and I’m giving it all I’ve got. And it does feel great.

How did it feel to go back into the Creedence songbook and play those songs?

It feels great. You are of course aware that those are my songs. Most people refer to this body of work as Creedence, but even the name Creedence is something I invented. I read a review the other day and the guy is talking about Creedence imagery. That’s cool. I know what he means. But even the Creedence part is John Fogerty imagery. I’ve had to share that all these years. That’s fine. But I hope that as time goes on, perhaps as the author I will actually get credit for my own work.

You had a long break of ten years before “Centerfold” and then another long break after “Eye of the Zombie.” What happened? Was it more of the same?

Yeah. I’m sure you don’t want to stay there too long. I spent a long time, basically, after “Zombie,” you knew I had already been away ten years before and it happened again. Well, what happened? I spent a lot of time after the “Zombie” album trying to resolve all this stuff. It all seems silly to have it keep going on. I keep reading reviewers in the paper saying why didn’t somebody do something? Well, I actually tried. I had meetings with Saul Zaentz. I had conversations with the other guys in the band hoping at the time that I could put an end to all these problems and have everybody retain their dignity, not give up. It’s called compromise. And make it resolve so we could all move on. Unfortunately, at least from my perspective, everybody ended up staying where they were and stabbing me in the back. I just got a very bad taste in my mouth. I spent a little over three years, from 1989 to 1992, I guess, in a very conscious high energy effort to make this calm down, to make it resolve. It’s the only thing you can do in life. And it didn’t work. So when things happen like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, I didn’t want to play with the other members of the band. That was no surprise to them. Here we were trying to resolve things and they were calling me names and doing bad stuff to me all over again. How can I say it? It was an obvious answer to what was going on in my life at the time [laughs].

Did all this strife prevent you from focusing on music?

I’ll tell you something that happened. I had tried very hard to resolve everything with Saul Zaentz, including settling my libel suit from my song, “Zanz Kant Danz” [Zaentz sued Fogerty for defamation of character over the song, which included the line, “Zanz can’t dance, but he’ll steal your money”]. I ended up giving him a very large check in return for which he was supposed to then sell me at a fair market price my own songs – which rolls off the tongue rather funny, but that was the position I was put in. But I really wanted to acquire the rights to my own songs. Well, he reneged on the deal after he got the first part accomplished, the part where I gave him a huge check. I was in such a state, I was so angry I could hardly think straight. I called up Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone. I said, “Jann, I got some really bad stuff happening, I would at least like to tell the world. I’m so caught up in it, I feel I should at least be able to tell the world about it. Because I can’t go on.” He graciously offered to let me tell it in the pages of his magazine. Of course there were new bad things that had happened, but this was a story that everybody had already heard before. A part of me knew people didn’t want to read this all over again. Somehow, just the fact that Jann Wenner agreed to be my voice, to let me tell the truth, I loosened up. It’s like that big terrible rubber band that was tied tight around my heart loosened up knowing that I had a chance at least to tell what happened. So I ended up not having to tell it, if you can follow that. So that was a resolving thing for me. I never cashed in the chip and followed up Jann’s offer. It would have been overkill telling the same story. but at least I felt I had somebody on my side.

You’ve said that “Blue Moon Swamp” was influenced by a trip you took to Mississippi. Did you go and then decide to do the album or did you decide to do the album and then go?

They overlapped. They were totally disconnected in my mind. I started working on the new record in early ‘88, at least trying to write songs, somewhat unsuccessfully. The first step is getting the songs. And then somewhere in late ‘88 is when I had the plagiarism trial [Zaentz sued Fogerty, claiming the song “The Old Man Down the Road” was a copy of the Fantasy-copyrighted “Run Through the Jungle” and Fogerty had plagiarized himself; the case was decided in Fogerty’s favor]. I had already met my wife to be [Julie Kramer] and by 1988 we were committed to each other and moved in together. She knew I was working on songwriting. Somewhere around ‘89 I kept having the urge to go down to Mississippi, but I didn’t even know why. I didn’t understand it. So I squelched the urge, because I didn’t know what it was for. But by 1990, I had to go. I still didn’t know why. I thought I will at least put in order the chronology of all the people I know about – Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed – and kind of get it all sorted out in a logical list of who came from where, when they came, who influenced each other, that sort of thing. For some reason that was very important to me. At the time I couldn’t have explained to you why. Now remember that at the time I was trying to write songs, too. But when I went to Mississippi I wasn’t trying to write. At least at first. I was being a researcher, like a paleontologist digging up dinosaur bones. That’s how I felt. I just had to learn all this stuff. I was a student on the prowl for information. Only later did it start to come out to me that something important had happened to me, or let’s say was revealed to me, while I was there. And what was revealed was that the music is by far the most important thing. The very fact that I had gotten all caught up in the other junk in such an uptight way that I had to call up Jann Wenner shows that things were lopsided. Everything was lopsided. Because in Mississippi I stood at Robert Johnson’s tree, the tree he’s supposedly buried under. It was very symbolic to me. I realized that all I knew about Robert Johnson was his music, his songs. I stood and thought about that. I don’t know who owns them now, but I thought it’s probably some guy in a tall building in New York City who never met Robert. I don’t know, it’s not important. All I know is the music. That’s what’s important. That’s the deal here. And as time went on, even when I got back home, I thought about that tree. I said, “John, you don’t want it to be 50 years from now and some guy is looking at your tree and all he thinks about is lawsuits” [laughs]. You want him to look at your tree and go, “Those songs are great. The music is great.” That was what was revealed to me. It’s about the music, not all the crap on the side.

What did you do in Mississippi? Was it a solitary time or were you hanging out in juke joints?

It was very much solitary. I was by myself. I had a camera. I took hundreds of pictures and I’m not in one of them. All those little towns have the water towers with the name of the town on ‘em, that sort of thing. I did a lot of reading, read a lot of books so I could understand what Friars Point was in Robert Johnson’s song [“Traveling Riverside Blues”]. I met a few people. [Writer/producer] Jim O’Neal in Clarksdale, he’s sort of a pivotal figure himself. He’s the real deal, because he gave it all up and moved South himself. He and his wife took me to a juke joint in Clarksdale one night and I met Big Jack Johnson and that was neat. But that was a sidebar event. It was important, but what I was really listening to were archives, records that were 30, 40, 60 years old. After reading about Charley Patton and not knowing about him before this trip… I didn’t grow up with knowledge of him the way a real smart musicologist or a person in Mississippi would. He just wasn’t in my consciousness ‘cause he wasn’t on the r&b radio in 1952. So having started to read and learn how important Charley was, and then to find out there was a record, I went, “Oh my goodness, you mean they have records?” It seemed like it was Moses. I tracked down a cassette, put it on in the rent-a-car, that voice came out of there and I turned white [laughs]. I heard that voice. It was Howling Wolf and even that guy who sang “Run Through the Jungle.” I just went, “Oh my god, that’s where it comes from.” It just blew my mind. I had no idea it would sound like that. Robert Johnson has a high sweet voice and Son House has a powerful great voice. My favorite guy from that era actually is Son House. I guess Robert is the one who distilled all that music into one convenient location. But when I heard Charley Patton I just couldn’t believe it. It was like hearing the voice of Moses. I have great pictures. I went back there like three, four different trips. In one of them it’s a deluge, just absolutely pouring. You cross this little road there and cross this little road to Dockery’s [the plantation where Patton lived and where John Lee Hooker and Howlin’ Wolf heard Patton play] and there’s this little church with a graveyard where some of the Pattons are buried, Charley Patton’s wife, or one of them. Anyway, it started to rain while I was going through that particular graveyard and it was pouring on Dockery’s there, they have this little gas station there. It was really neat to be able to experience it in person.

The new album sounds as if it could have been recorded today or years ago. Were you going for a timeless quality?

I think the feel isn’t something I do on purpose, but when I’m done doing it I look back and say, oh yeah, I did it like that again. As I’m doing it I tend to think in terms not of a specific time but of a more general human way of feeling, a general human place that could have happened anywhere to human beings, rather than specifically to the guy who was at the L.A. riots in 1992. I tend to want to place them in a more epochal sense, I guess.

There’s something about the music that seems innocent and youthful. There’s little trace of bitterness. Maybe the word I’m looking for is unspoiled. You almost sound like someone who never grew up.

I get a lot of that from my wife, Julie. She’s helped me reconnect with the curious, joyful person and push the bad stuff, the baggage, push it to another place. I know its there, but I don’t have to open those bags every day. Just put ’em over there. Yeah, that happened, but if I use my time for the joyful stuff, perhaps I’ll never have to open those bags again. That would be great. Julie is the one that keeps me focused on the joy of music and the joy of life. Because the two of us really do have a great life together. Every day we help each other, back each other up and help each other feel the power and joy of what we share together.

Do you think you’ll be making more records faster now?

Very much so. I went right in a couple of months ago and did a few songs for B-sides of singles because I didn’t want to take songs off the album. And that was a fairly painless process. It only took a little over a week. It wasn’t all usable, but 80 percent was. And we worked on five or six songs. That’s a half an album in 10 days. So I feel real confident that I’ve learned how to do this. And what people to call [laughs]. I expect I’ll have another album out in a couple of years. It depends on the life of this one. Certainly I already should start writing the songs that are going to be on that next record.

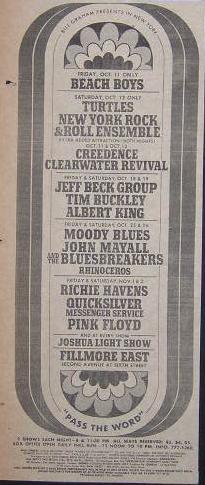

[As the interview was about to draw to a close, I asked Fogerty if he recalled a concert at the Fillmore East I attended on October 12,1968. The New York Rock and Roll Ensemble opened, followed by CCR, followed by the headliners, The Turtles (the previous day at the Fillmore East, CCR had opened for the Beach Boys). After CCR’s last song, Fogerty told the audience he had planned to finish the set that night by smashing his guitar on stage, but before the show he had been introduced to a young guitar player, an adolescent, and decided he would give the guitar to him instead of destroying it. It was a memorable moment, one I clearly recalled, as did Fogerty.]

His name was Sean Levitt. I certainly remember that night. It was cool you were there. I was having so much trouble with the guitar itself. It was a Rickenbacker and it had some design flaws. Anyway, that was a much more positive thing to do. And I’ve never broken one.

[I do not remember doing much, if any, research into the story of Sean Levitt at the time of this interview, probably because I knew it was off-topic and not something I was going to use in my piece about Fogerty. Now I discover that Levitt went on to become a guitarist of some renown, at least among a sliver of jazz cognoscenti. In fact, he was already a performer and recording artist at age 13 when Fogerty handed him his guitar that night at the Fillmore East. Levitt was a member of the Levitts, a family band comprised of vocalist mother Stella, drummer father Al and their six children. In 1968 they released “We Are the Levitts,” a flower power era pop/jazz album on the legendary ESP label. A handful of jazz pros assisted, including Chick Corea.

It appears that not too long after the album’s release the Levitts moved to Europe. Sean ended up living in Spain in the ’80s and ’90s, where he was known as a highly skilled post-bebopper. Plagued by substance abuse, he died in 2002. A “Sean Levitt Documentary Project” Facebook page offers little information, but indicates a film about him is in the works.]