Jay Geils (2005)

Jay Geils made his mark playing blues and his fortune playing rock and roll. But his first love was jazz.

Jay—who died on April 11, 2017 at age 71—made that clear when I interviewed him at his split-level home in Groton ten days before a date at Tempo, a Waltham restaurant, to celebrate the release of his debut solo album, “Jay Geils Plays Jazz!” The presence of the exclamation point in the title seemed like a buyer beware warning for fans expecting a rock or blues session, but after hanging with Jay I realized that exclamation point represented something more: his own excitement. Playing jazz was Jay’s dream come true.

“I play what I want to play, when I want to play, where I want to play. I’m doing exactly the music I held dear as a kid and I’m getting to play it on my own terms. It’s perfect.” — Jay Geils, on his post-rock and roll career.

At the time of this interview, Jay still was performing on rare occasions with the J. Geils Band, which had reunited in 1999 after a 15-year breakup. Two weeks before our interview, the Geils Band had played a benefit for the Cam Neely Foundation in the ballroom of the Charles Hotel in Cambridge. Tickets sold for $2,500 and fans snapped up every one, knowing that this might be their best chance to see the Geils Band in a small venue—or anywhere, for that matter. Given the history of band tensions, any gig might be the last.

After the band’s set, Jay went up to his room in the hotel to change out of his sweaty clothes before mingling with the attendees, who included Neely Foundation boosters Michael J. Fox and Dennis Leary.

“I flipped on ESPN’s ‘College Game Day,’ Jay told me, “and you know what I hear? My guitar!. They’re playing “House Party.” I thought, ‘Gee, I was just playing that song onstage a few minutes ago’.”

Jay laughed. We sat in a den filled with books, CDs, auto parts and a big screen TV. Behind French doors was a much larger room, one wall containing his collection of vintage amplifiers, two other walls filled with guitars, most of them hollow-bodied electrics. “My taste in guitars is the same as my taste in women,” he grinned. “I like big blondes.”

Jay went on to explain the evolution of his jazz recording career—how he went from making two mid-’90s albums with Geils’ harp demon Magic Dick under the moniker Bluestime to working in the 2000’s with New England guitar mainstays Duke Robillard and Gerry Beaudoin as New Guitar Summit and on to signing a deal with Alberta, Canada-based Stony Plains Records for his solo debut.

March 11, 2005

In Jay Geils’ home, Groton, Massachusetts

So how did you come to have Stony Plain put out your new album?

When we started doing this New Guitar Summit stuff, we made a deal [with Stony Plain] to do two CDs. Then I wound up owning this video shot at the Stoneham Theatre. so they picked that up. So I said, “Well, I’ve got this ‘J. Geils Plays Jazz!’ CD I made totally on my own as a labor of love, basically a bunch of tunes and people I’ve wanted to work with for 35 years. I said, “Well, you’ve got Jay, Duke and Gerry on a CD, you’ve got us on a DVD [‘Live at Stoneham Theatre’]. So he said, “Yeah, we’ll put out your CD.” So we made a deal with them. And I’m gonna make another one for them, which basically I already have in the can. Similar idea, maybe just a little more modern. And instead of so many different guys, I used principally just two guys, Billy Novick on alto and Doug James, an old buddy of Duke’s. Because I love that baritone sax-electric guitar thing. There’s a record famous among guitar players and jazz musicians called “Billy in the Lion’s Den,” from the ‘50s, with Bill Jennings on guitar, a favorite of mine and Duke’s who a lot of people don’t know about, and Leo Parker, the famous bari sax player, no relation to Charlie Parker. Every tune is just great. So “There Will Never Be Another You,” which is on the CD that’s out now, I took from that record and brought Crispin [Cioe] from the Uptown Horns to play on that. In the most recent one, I did another one from that record called “Stuffy,” an old Coleman Hawkins tune, with Doug James—which came out just as good.

;

So you’ve been recording on your own?

I have a great studio I work in that’s 15 minutes from here on the Acton/Chelmsford border. I walked into it one day, on a whim one day, driving back from Cambridge. I’d seen an ad for it and I knew the address. I swung by and introduced myself. Great, nice big room. Clapped my hands twice and said, “Yeah, this is the place.” I hooked up with a very nice engineer [Timm Keleher] and it’s my home away from home. I even have a full set of vibes that I play a little bit and I moved them over there [laughs].

Do you see a progression from doing Bluestime to New Guitar Summit to this solo album, what might be viewed as a gradual shift away from the blues?

It’s actually a return to the music I’ve been in love with since I was a kid, which is straight ahead jazz. Actually, the route is from jazz as a fan and a trumpet player, which I was in grade school, to blues with the J. Geils Blues Band in the ’60s. When we [Jay and Geils’ harp player Magic Dick] formed Bluestime, it was really a continuation of the old J. Geils Blues Band, with a lot better players. And Dick and I had got a lot better. And then the J. Geils Blues Band became the J. Geils Band and we made some rock and roll records and that whole story, which you already know.

When I was a kid, my father was a big jazz fan. He graduated from Evander Childs High School in the Bronx, New York, in like ‘37 or ‘38. He saw Benny Goodman at the Paramount and my mother danced in the aisles, like they showed on Ken Burns “Jazz.” So all the music I heard was Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Artie Shaw, Duke Ellington. Around 1956 he took me to my first jazz concert, which was Louis Armstrong and the All Stars. I had been playing trumpet for two or three years and there was Pops, right there in New Jersey. I remember I saw the Maynard Ferguson Big Band and was completely blown away. It was the loudest band I’d heard till that point. They were spectacular. When I went off to college [Worcester Polytechnic Institute] in 1964, my parents moved back to New York City from New Jersey and lived on the outskirts of Greenwich Village. So when I’d go home, I’d just walk down to the Village Vanguard and the Village Gate. I saw Mingus and Miles. For my 14th birthday present, my father took me to see Miles Davis at the Village Vanguard. February, 1961.

So given your musical leanings, were you unhappy when the Geils Band got deeper into pop and rock?

No, I was never a jazz Nazi. I liked all kinds of music. And I understood, particularly when the Rolling Stones progressed a little further after two or three albums, I said, “These guys got something going on here.” Actually, in the late ‘60s, we were a better blues band than the Rolling Stones. Mick played terrible harp. And Keith and Brian clearly could not play a blues solo like Eric Clapton or Peter Green. But I got it. And plus, at that time I wasn’t good enough to be a jazz musician. I’d spend hours learning a Charlie Christian solo, but only one based on blues changes. To tackle a tune at that time like “Body and Soul” or “All the Things You Are”….I knew the tunes, I’d been hearing ’em since I was a kid. But I couldn’t play ’em [laughs].

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s, when I was in the fortunate position of having a little time on my hands and a little money in the bank, that I was able to go back in the woodshed. I could play blues, but I wanted to get into those jazzier blues changes—not to get too technical, with substitute passing chords and those kinds of things. And then I got on top of the rhythm changes thing [the chord progression in George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm”], which is the basis for a whole bunch of jazz tunes. So that leads you to trying to tackle some standards. Having gotten to know a lot of the first-call jazz players around Boston, that’s the progression for everybody, pretty much. You learn to play the blues, then you learn to play them a little jazzier, then rhythm changes, and then, “Okay, tackle this.”

I didn’t play at all from around ‘84 [when the J. Geils Band broke up] to ‘91. Oh, I played a little bit. But I was a little blown out from 15 years of rock and roll. All we did was make records, go on the road, make records, go on the road. I once calculated that from 1971, when we did our first national tour—which was opening for Black Sabbath—to 1983, right after we had our biggest year with “Freeze Frame” and the Stones tour, on average, I was on a plane playing a show every third day. After 12 or 13 years it wears you down. And playing a rock and roll show, it’s pretty much the same thing every night. The fans want to hear what they want to hear. It’s not like a jazz thing where you can take eight choruses. Or like Duke [Robillard] likes to say, “Go ahead, take 27 choruses” [laughs].

So at a certain point did you get itchy to play guitar again?

What happened was I was deep into the vintage racing sports car business. The business is still flourishing in Ayer. I sold it in 1996, and the guy who bought it built this whole new big building across from Fort Devens, KTR Engineering. They got the 45-foot trailer truck and the Ferraris to Monterey and the whole thing. I had the business with two or three other guys. Some of the stuff we were not equipped to handle, like inspection stickers and fixing the a/c. I was more into rebuilding cars from the ‘50s and ‘60s, so I sold the business to someone who could also do the more mundane things, like servicing later model cars. It turns out this guy, Gary Wilson, played guitar in a little local blues band [Blood Street Band]. Halloween, 1991, Gary’s band was playing a gig at a Chinese restaurant. One of the guys who was working for me said, “Hey, Gary’s band has a gig and they play a lot of your tunes.” So I went down to check ‘em out and they were pretty good. I said, “Y’know, I could point out a few things to you guys and make your band a little better. So I became their player/coach. I’d go once a week to a rehearsal and if they were playing a gig I’d sit in. What’s funny is that [Magic] Dick in 1992 had been invited to play with some musicians at a festival in Holland. He came back and called me up and said, “I just played for 10 days in Holland. You wanna get together and play some blues again?” I said sure. And that was the start of Bluestime. I had to get back in the woodshed, even for my blues playing. Jerry Miller—great mandolin player—was playing some jazz standard with the bass player, “All the Things You Are,” I think. I thought, “Gee, I know that tune. I’ve known it since I was six years old. But I can’t play it.” And right there I decided, god damn it, if he can do it, I’m gonna get on top of this shit. And I did.

[Here Jay discussed a local band he was working with: “I just produced a [local blues] band called the Installers, which isn’t really out yet. They’ve got a guitar player Kevin Visnaskas…..” “Nail It,” the Installer’s debut, was produced by Jay, who played guitar on several cuts and even wrote the liner notes.]

So you taught yourself to play jazz?

Oh yeah. I don’t think I’ve ever taken a guitar lesson. But I’ve read all the interviews with the great guitar players—Barney Kessel, Wes Montgomery—and they all say the same thing. “The first thing I did,” they say, “is learn all the Charlie Christian guitar solos from the Benny Goodman Sextet.” I thought, “There may be a clue here” [laughs]. His approach to blues and chords with changes was very modern at the time. And what was particularly important was that he was playing electric guitar, which had only been invented about five years before that. To me, he’s one of the top five undersung guys in American music. He took an instrument that had just been invented and immediately knew how to make sense out of it.

Is that why you open your CD with a Benny Goodman cut [“Wholly Cats]?

Yeah.

This is your first solo album. Is it a sign that you feel you’re able to handle center stage as jazzman?

To a degree. I still would have a hard time doing two full sets leading a guitar trio. Unless we played a lot of blues, I’m not sure I could pull that off [laughs]. I’m not on top of that much of the standard jazz repertoire. I’m not quite at the level of someone like John Turner, the bassist in my band, who knows a thousand tunes.

Plus the other thing that happened was I met Gerry Beaudoin for the first time in ‘93 or ‘94. We met at a vintage guitar show in Boston. I have the same problem with guitars that I do with cars—I like old ones. Gerry was playing with a guy and had a CD he had made with Duke called “Minor Swing.” David Grisman is on some of it. I introduced myself and we hit it off. We got together a couple of times and here was exactly the guy I wanted to play with. He was already dialed into this music. He knows more chords than me and Duke put together—and he even knows the names of them [laughs]. Duke and I are a little more swing oriented. Gerry is a little more harmonically complicated. He’s slightly more sophisticated. A lot of people say on the records I made with Duke that they can’t tell us apart, which I take as a great compliment. Duke is spectacular. I’ve known him since the ’60s. We once played a gig in Connecticut, J. Geils Band and Roomful of Blues. It was so long ago Roomful didn’t have horns yet. So we’ve known each other a long time. He was the first guy I heard up here where I said, “Whoa, he’s coming from where I want to come from.” Because most guitar players were into Cream and Hendrix, and I was into B.B. King and Louis Jordan swing. Not three chords, maybe five or six. And Duke was the guy.

Gerry played a lot at a joint in Waltham called The Rendezvous. He said “Why don’t you come down and sit in?” We played that night and it was great. Turned out he knew Duke, too, and we all got together. We all loved the three-guitar harmony thing. We all loved the same music, that late ‘30s, early ‘40s swinging Basie stuff. So we worked up arrangements of “Flying Home” and “Broadway” in three-part harmony. There’s an interaction you get with that that’s unlike anything else. Duke says in the interview section of the DVD, “Hey, I love playing with horn players, but there’s something special about three guys who play the same instrument getting together. We’re not competitive. We just want the music to sound great and swing.

So clearly this new record was a labor of love for you.

Absolutely. I’d been thinking that I’d like to make a record of these tunes I’ve loved for literally 35, 40 years. What really kicked it off was Gerry. We’re partners in a label, Francesca Records. We’ve done some local things, including one or two of his CDs. He started putting out a jazz guitar sampler, which is not out yet. He asked me to do two cuts. So that’s when I decided to check out this studio, Wellspring Sound [in Acton, MA]. So I went in and worked up a couple of tunes with John Turner and [drummer] Gordon [Grottenthaler]. Brought in Rich Lataille from Roomful. “Honey Boy,” with Rich on sax, an old Bill Doggett tune with another undersung guitar hero, Billy Butler, who made a few solo albums but is mostly known as the guitar player on “Honky Tonk.” My old friend Barry Tashian from the Remains was the first guy who turned me on to this Bill Doggett stuff with Billy Butler. I’m talking 1968 or ‘69 that I got hip to these tunes. That shows how long I’ve been waiting to record this stuff!

[Above: Three classic Bill Doggett cuts, featuring two of his best guitar-playing sidemen—Billy Butler and Bill Jennings. The first two (“Honey Boy,” and “Oof,”) feature Billy Butler. The third, “Big Boy,” features Bill Jennings.]

Do you think you might continue your progression and do even more modern stuff on your next CD? How modern would you want to get?

Well, I’m talking about moving from the ‘40s maybe into the ‘50s [laughs]. What I did on this CD was a very specific goal of mine. Virtually no overdubs, except when I had Crispin Cioe put all three horns on “L.B. Blues.” I think that’s the only overdub on the whole record. No fixes, live, in the room. I was going for that old, classic, to some degree Blue Note sound. And even further back. I’m not really a jazz historian, but I love reading about and seeing pictures of the old days. And what you see is one or two mikes. I wanted to do an album that had that energy and that sound. I wanted to get that feel. What I’ve done for the next album [“Top Tappin’ Jazz,” released in 2009] is the same basic idea but a little bit more separation. So if you needed to, you could go back and fix something. Just a little more modern approach. [Here Jay went into detail about how he absorbed technical production know-how from observing and working alongside Bill Szymczyk (who most famously produced the Eagles as well as B.B. King’s “The Thrill Is Gone”), producer and engineer of six J. Geils Band albums. Said Jay: I may have not got credit for it, but I’ve been producing records since 1971.”]

[Above: Bill Szymczyk (sitting) with the J. Geils Band, left to right: Peter Wolf, Jay Geils, Magic Dick Salwitz, Stephen Bladd, Long View Farm engineer Jesse Henderson, Danny Klein, Seth Justman]

What did you think when the Geils Band was nominated but not voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Were you disappointed?

No, it was not a big deal. When we first got nominated, I didn’t even know about it. We didn’t get in this year, but maybe next year we will. [Several nominations later, they’re still waiting.]

[Here Jay got to reminiscing about Mario Medious, the legendary Atlantic Records promo man, who brought the J. Geils Band to the attention of Atlantic Records. Said Jay, “Mario was a really slick black guy. He called Jerry Wexler after seeing the J. Geils Band at the Boston Tea Party in 1968.” A Medious catchphrase, ”Man, that’s a whammerjammer”—gave the band the title for their instrumental showcasing Magic Dick’s harp.]

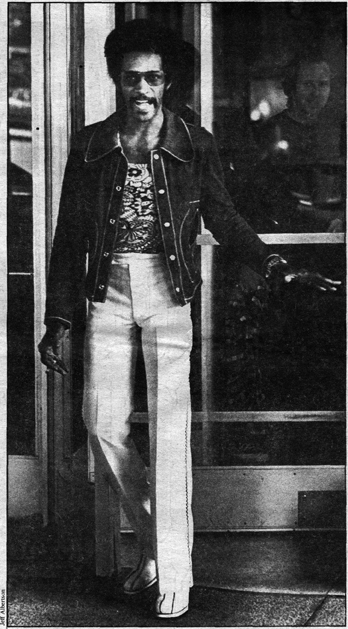

[Left: Mario “The Big M” Medious. Photo by Jeff Albertson]

The J. Geils Band reunited a week ago to play the Cam Neely Foundation benefit (for cancer care). How’d it go?

It was nice. We stuck to the classic stuff. We did “Centerford” as an encore. It was fun and it was for a good cause. It was nice meeting Cam and Michael J. Fox, but I never got to meet Dennis Leary, who I’m a big fan of.

Any other projects in the works?

Well, there’s the Kings of Strings, which is an acoustic jazz group with me and Gerry on acoustic archtop guitars with string bass and Aaron Weinstein, who’s a Berklee College kid who plays mandolin and violin.

Sounds like your pretty busy.

I consider myself semi-retired. I play what I want to play, when I want to play, where I want to play. I’m doing exactly the music I held dear as a kid and I’m getting to play it on my own terms. It’s perfect.