Jack Bruce (1993)

“I couldn’t be happier.”

I blew my chance. It only occurred to me today, two weeks after Jack Bruce’s death at age 71 from liver disease, that I should have thought to thank him for his part in my becoming a bass player. The first song I learned, copying him note for note, was “Sunshine of Your Love.” Playing it was such a thrill that I didn’t want to stop. For the next 12 years the only thing I did more than play music was sleep – and some of those years there was more music than sleep.

I was thinking about the unexpressed debt I owed Jack Bruce while re-reading this interview with him from 21 years ago. He will be remembered as one of the most adventurous bass players in rock. No one ever pushed Eric Clapton as hard and as far as Bruce did in Cream, where he forcefully asserted himself as a fully equal partner to both Clapton and Ginger Baker, no easy task. His melodic approach to the bass, his eagerness to improvise and his willingness to take risks made his forays into jazz and the avant garde inevitable. Yet Bruce also knew how to lay down a simple, killer riff – the key to great rock and roll.

Bruce never achieved the fame of Clapton or the notoriety of Baker, though he was as much a virtuoso as either of them. But lack of celebrity was of no concern to him. He found his joy in musical exploration and his work over the course of more than half a century – whether pushing boundaries with the likes of Tony Williams, John McLaughlin, Kip Hanrahan, Carla Bley, Michael Mantler, Vernon Reed and Lou Reed, or powering power trios with Leslie West, Robin Trower and Gary Moore – is audible, inspiring proof.

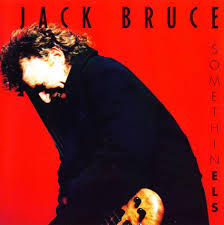

I interviewed Bruce as he was about to launch a tour in support of a new album, “Somethin Els,” on which reunited him on three tracks with Clapton. The release was a long time in the making, in part due to Bruce’s drug addiction. Whatever his personal problems, I’m glad to be reminded that, at least when it came to music, he “couldn’t be happier.”

MARCH, 1993

San Francisco, rehearsing before start of tour

So are you planning to play any songs from the new album [“Somethin Els”] on tour?

I’m doing a couple of things. But it’s difficult. The last time I did a tour I did very long shows – part new material, part a mixture of things. This time I’m just doing a selection from the many things I’ve done.

The album was recorded over the span of six years?

Basically it didn’t start off as a record. It started off with me making some little recordings and gradually grew into one. It just became more serious. I started off recording at a friend’s studio and helping him put the studio together and just writing things as I do all the time. Eventually he said, ‘Why don’t you make a record of this stuff?’ I went back and few times and eventually finished it off.

You’ve got Eric Clapton playing on several tracks.

The songs were written early on, but the recordings came near the end of the project. Like a lot of things I write, those songs were written with a definite person in mind. I wrote those three songs with Eric in mind and also Maggie Reilly, who sings on one of them. I gave him a call and he came along and did it.

[It escaped my notice at the time of this interview, but two of the three Clapton tracks on “Somethin Els” actually had made their first appearance as “previously unreleased songs” on “Willpower,” a 1989 Jack Bruce retrospective, which you can hear in its entirety above. The opener is the Cream-like title track; the final cut, “Ships in the Night,” features singer Maggie Reilly as well as Clapton.]

Were you confident that Eric would want to do it?

I never had any doubt that he’d agree to play on them. I wrote them mainly because one of my sons plays guitar and he sounds a lot like Eric at times. We were doing a little home demo and the songs just made me think of Eric, really. I recorded the songs with my son [Malcolm] first. He’s 22. He’s in a band somewhere in the Los Angeles area with Ginger Baker’s son, Kofi Baker.

What’s the name of their band?

I don’t know the name of the band. [laughs] They don’t call. [The name of the band was Lost City. More recently Bruce and Baker fils have been performing as the Sons of Cream.]

Do you have any other kids?

I’ve got two other sons, one 24 and one who’s three months and a couple of daughters in there for good measure. My oldest son is a keyboard player. He’s a jazz player in London. Does a lot of theater work as will, with the Royal Shakespeare Company sometimes. His name is Jonas. [Jonas Bruce died in 1997 after an asthma attack.]

You could make a Bruce family album.

Maybe. Yes. [laughs]

The story about Cream breaking up is that it was because of the acrimonious relationships between the three of you.

I don’t think the band did split up under particularly acrimonious circumstances. It was a fairly amicable separation. I think a lot of the so-called bad feeling was something that came up in the press when you say things, especially in England, and you get misquoted. I don’t think there ever was tremendous bad feelings. We had our little differences. But all three of us would each other from time to time. I did a TV show with Eric and that’s when I asked him to play on the record. He asked me to do the TV show, so I asked him to play on the record.

So why did Cream break up?

Just simply because Eric and myself thought we had done as much as we could with that band at that time. We wanted to move on and do other things. I wanted to work with a larger group. My first solo record [“Songs for a Tailor” in 1969] had four or five horns and things like that. That was the simple reason. We’d gone as far as we could at that point with the trio format and three guys. Simply that.

To me, one of the things that made Cream special and unlike previous rock or blues bands was the creative tension between your freeflowing bass and Eric’s formally sculpted solos.

Yeah, I think the function of a bass player in any band is to be a catalyst and to make the other guys sound good. So I would agree with that.

Some people felt as if you and Eric were in competition. Did you have any musical conflicts with him?

I don’t remember any musical conflicts at all. None whatsoever. The way we used to play was a very upfront way so that people imagined it was a competition. But it wasn’t like that at all. We were just going for it!

You did most of the lead vocals in Cream. Now Eric is a Grammy-winning singer. Are you surprised?

Not really. Certainly not at the Grammy Awards [laughs]. I always really enjoyed his singing and tried to encourage him to sing more. I think in those days he was a little insecure about his singing. I certainly was, but we needed a lead vocalist [laughs].

With you and Eric and (lyricist) Peter Brown your new album is in part a three-quarters Cream reunion.

Peter and I are a songwriting partnership in the old sense. We did write for Cream and maybe if that band hadn’t happened we would have come together as songwriters. So I’m really glad that did happen. Because here we are still working all these years later. He’s written on every solo record I’ve done. We write a lot.

What about Ginger? Are you in touch?

We did a lot of playing in 1990. He was on the road with me in Europe and places like Israel.

The stories of you and him butting heads go way back to the early ‘60s, before Cream. Is it true that he was responsible for getting you tossed out of the Graham Bond Organisation?

Yeah, we had some very strong musical differences in those days. That’s when I was trying to formulate my bass style. He thought I was playing too much. But I was being influenced by great bass players like James Jamerson. I wanted to come up with my own approach to the instrument. I was very discouraged when I was fired from that band. But then I worked with Marvin Gaye in London and that was very encouraging. He asked me to join his band, which I unfortunately was unable to do because I was about to get married. I wasn’t possible. But he was certainly very encouraging and told me the direction I was going in was great. That was very important to me. Quite often I think with players who are trying to do new things you meet somebody. You might be very discourage by people saying what you’re trying to do is wrong. But if you’re fortunate you meet someone who encourage you enough to keep going.

I never thought of it before, but now that you say it I can see the connection between your approach to bass playing and Jamerson’s.

The interesting thing is he’s playing a very functional role, but also expressing a lot of melodic ideas. And that’s what I thought the bass could do and what I tried to do in my own way.

Did you regret not taking the gig with Marvin?

I didn’t regret it, but it would have been interesting to see what would have gone on. But the way things did work out, they couldn’t have gone much better.

Certainly you’ve had a lot of success as a musician, but not like Eric, who’s a household name and a superstar. Do you think you deserved more recognition?

Not at all. I’m very happy with the way things have gone. It’s by choice. Whatever choice you make there are gonna be good things and bad things about it. I’m very happy that I’ve been able to do a lot of different things. I’ve explored a lot of different areas of music. I don’t think that would have happened if I’d gone the other route and tried to be a pop star. I’m much happier following the different course I have. I couldn’t be happier.

I have a blues record. I’m working on that. I’m hoping to finish this year with people like Charlie Watts, Robert Cray, Albert Collins. I’m also planning a record in October with the Meters in New Orleans. We’re doing a TV special on my 50th birthday which I’m very excited about. It gives me an opportunity to bring in a lot of people I’ve played with over the years. That’s gonna be fun. After this tour I’m doing a thing with a symphony orchestra in Belgium. I’m also working with the Balanescu String Quartet as a singer. I have to do more and more things just as a singer.

Have you heard Elvis Costello’s record with the Brodsky Quartet? Is there any resemblance to what you’re doing?

Absolutely none. What we’re doing is a little further out. A little bit more atonal.

Tell me about what you’re going to do with the Meters.

That’s gonna be Jack meets the Meters. I’ve become very good friends with [guitarist] Leo Nocentelli. [Bruce had previously worked with Nocentelli on several projects masterminded by Kip Hanrahan. I can find no information indicating that a Bruce/Meters recording ever took place.]

And do you think that there might be a Cream reunion sometime down the road?

I think it’s, ummmmm, how can I put it? It’s a possibility. Yeah, we may get together and make a record. That’s a possibility. I have no mixed feelings having recently played together for the first time in 25 years and finding out that there’s still sparks, that the old chemistry is still there. I think it would be a challenge, definitely. But it would be fun as well.