B.B. King (1980)

“A guy comes out of the gumbo, he likes to walk on concrete awhile.”

October 14, 1980

Lippman House, Harvard University, Cambridge

When B.B. King came to Harvard University, it was a special day. Not only for the fortunate few who got to witness an intimate performance in a small wooden house on the Harvard campus, but for B.B. himself. He knew better than anyone the distance he had traveled to get from his birthplace on a Mississippi cotton plantation to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he now was an admired, adored and appreciative guest at “the world’s greatest university.” And he was digging it.

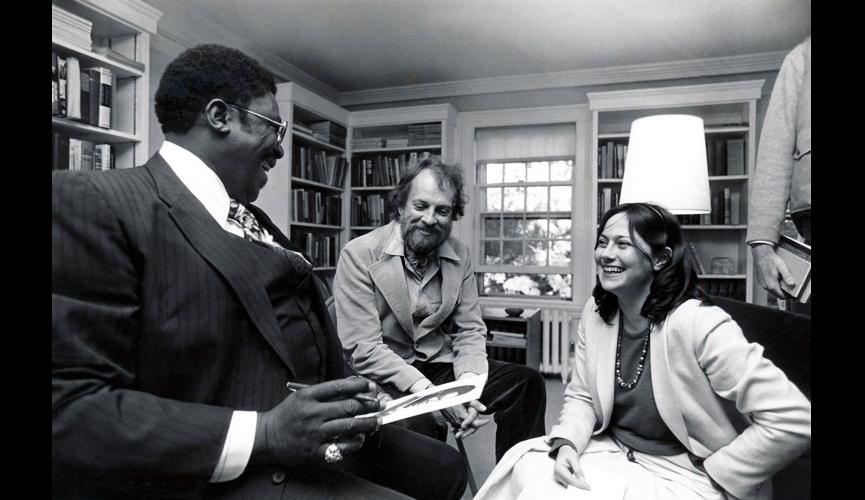

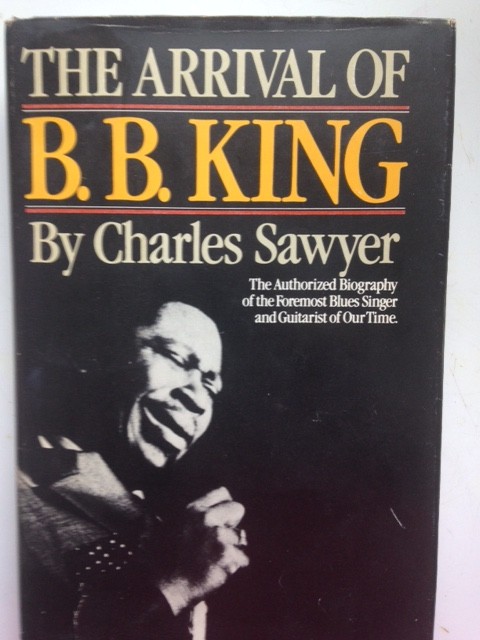

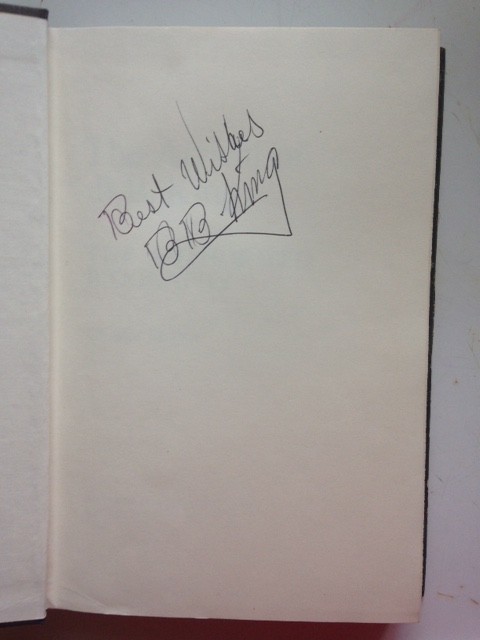

B.B. had come to Harvard to visit the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, an event occasioned by the publication of his authorized biography, “The Arrival of B.B. King” by Charles Sawyer in 1980 (16 years prior to his David Ritz-assisted autobiography, “Blues All Around Me”). Sawyer’s friend (and soon-to-be wife) Bistra Lankova was a Nieman fellow at Harvard’s and it did not take much convincing on their part to get B.B. an invitation to have lunch at the Nieman’s Lippman House and speak to the fellows. You can find Sawyer’s account of the day here, along with audio of his remarks at the lunch and B.B.’s entire half-hour post-lunch performance. Good reading, even better listening.

I showed up that day not knowing what to expect other than that B.B. King would be there with the author of his biography, which I had been given the day before by my editor at the Real Paper. I had little journalistic experience at that point, having made the switch from playing music to writing only 10 months earlier. Now I was getting the chance to talk to B.B. King. Yes, I was excited.

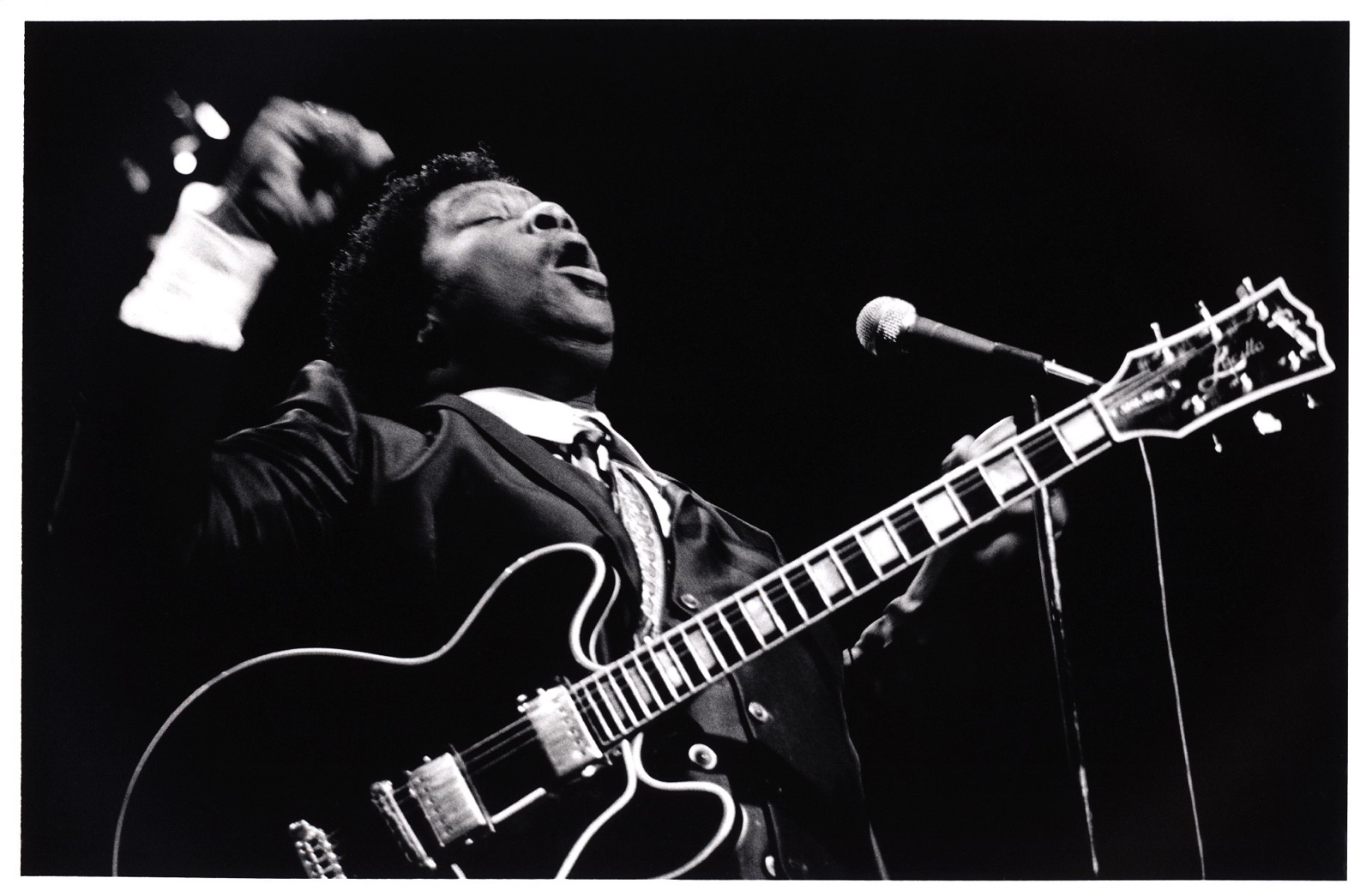

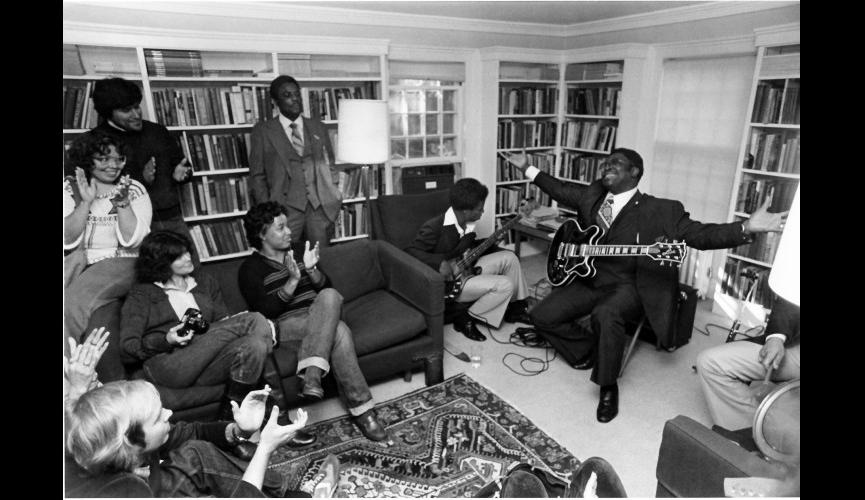

I arrived at Lippman House after the lunch (which I was not invited to) concluded. The gathering had moved upstairs to the library on the second floor. There were maybe 30 people crowded into the room: the Nieman fellows, Charles Sawyer B.B., his longtime manager Sidney Seidenberg, his valet, Norman Matthews, and three members of his band: bassist Russell B. Jackson, keyboardist Eugene Carrier and drummer Calep Emphrey Jr. The undersized gear they’d brought suited the size of the room. Carrier played a tiny keyboard and Emphrey a snare drum with brushes. And B.B., resplendent in a dark three-piece suit and tinted shades with his monogram etched in the corner of one lens, plugged Lucille, his black Gibson guitar, into a small amp.

B.B. claimed he was nervous, but it didn’t seem like it. He was smart, funny, articulate. The Nieman fellows were enraptured. As was I.

I stood in the back of the room, amazed to be standing some 20 feet away from B.B. King as he gave a private performance, the low volume somehow multiplying the impact of the musical portion of his lecture-demonstration.

After he’d finished playing, B.B., 55 at the time, turned to a man about his own age sitting nearby. “Now can you answer the question you asked me before?,” he said. “Am I better or worse?” Everyone laughed. “Better,” came the reply.

“Anyone can play the blues,” B.B. said. “You just have to learn three chords. What I’ve been trying to show is the emotions. The feelings. It’s kind of like seeing a good movie that brings tears to your eyes. Good blues brings that state of mind. It gives you a picture of what’s going on. Blues aren’t just one kind. There’s happy blues, too.”

As the audience dispersed, I stepped forward and introduced myself. B.B. stayed seated and graciously answered my questions as a few people stood by and listened.

“You can flatten a seventh or play a minor third, but that doesn’t do it,” B.B. said, responding to a question I failed to write down. “People thought you had to be in a dingy club where you can cut the smoke with a knife to play the blues. I don’t agree with that. You need a good sound system so you can reach the people, so you can touch each person individually. It’s like when I was working in radio. I’d think that I was talking right to everyone. It’s like ESP or something.”

Norman Matthews walked up and handed B.B. a glass of tea. B.B. handed him his his guitar in return. “You wanna take Lucille over there,” he said, pointing to his guitar case.

Then B.B. spied a little boy, about three or four years old, sitting alone and looking somewhat bewildered by the scene.

“I think I got a present for the little one,” B.B. said. He plucked a guitar pick out of his jacket pocket and offered it to the child, who mustered up enough courage to take a few steps forward and accept the gift.

I popped another question, sensing time was short.

After so many years of struggle, do you find you’re at a place in your life than you can now enjoy your success?

A guy comes out of the gumbo, he likes to walk on concrete awhile.

Are you referring to when you were coming up and playing the chitlin’ circuit?

I don’t use that expression, although a lot of people will call it that. ‘Cos I don’t want to burn any bridges. I might have to cross them again.

I know you have a busy tour schedule. How many nights a year would you say you’re out working?

I have a 10-piece band and we’re out working on the the average of 300 nights a year. On the other 64 days we’re trying to figure out which way to go [laughs].

Do you have any special projects you’d like to do beyond all the touring, some ambition you’d like to fulfill?

I would very much like to do a blues [TV] special. I’m always coming on these jazz specials or gospel specials. But I don’t play jazz. I play the blues. I’d like to do a blues special and have Johnny Carson or whoever, and have them on a blues show.

I wasn’t at the lunch today. Did you enjoy dining with a roomful of journalists?

We had a good time. Charles [Sawyer] spoke and had some interesting things to say. And there was some good food [smiles].

How does it feel being here at Harvard?

I get a little nervous, I guess. I didn’t finish high school. I used to feel bad when I’d drive by Ole Miss.

But you’re getting recognition now from all sorts of people and places, including Harvard.

Always better late than never.

Are there other performers out there that have the same deep feeling for the blues that you do?

There are so many.

Can you name one?

Aretha. A lot of the youngsters don’t even use the name blues, but the feeling is still the blues.

Being a musician is a tough life, but do you think it’s especially hard being a blues musician?

Someone once said to me, that’s like being black twice.

These days it seems like there are more white blues fans than black blues fans. Does that matter to you? Do you think white people understand the blues as well as a black audience?

You don’t have to be poor to understand feelings of disloyalty or to feel abused or sad. But if you live through these things you can understand them even better.

Do you still play black venues. Does the chitlin’ circuit still exist?

The circuit has changed quite a bit. But nothing is destroyed. New clubs are constantly coming on the scene to replace the old ones. What was the name of that place we played last night in Providence? That’s a new place [Center Stage in East Providence]. We play quite a few places where the majority is black, but there aren’t so many of those places anymore. Once a year we play at what they call a homecoming in Mississippi. Charles talks about that in his book, about doing that with Mayor [Charles] Evers [older brother of Medgar Evers and the first African-American mayor elected in Mississippi since Reconstruction]. We do it for whatever we can get. We stay for a week or ten days and try to break even. You need to do that. I need a chance to get back to where I came from. You don’t have as many people into blues music today as when I was coming up. Now the kids are into a different kind of music. If you’d go in there with a blues singer called B.B. King, they’d say, ‘When did he get back from Mars?’

Disco has taken over a lot of the music scene. What do you think of it?

I like disco. I think we have enough people to support all types of music. I don’t think we should go backwards. Except for 55 miles per hour [laughs]. I don’t dig that.

Do you listen mostly to blues or do you try to keep up and check out other kinds of music, stuff like reggae or new wave?

I mainly get to hear things on radio and records. I hardly get a chance to go out and hear anyone else. Last night we had Duke Robillard there with us and I enjoyed him. But when I’m home I might like to listen to some of my favorite things. Or I might not want to listen to any music at all, just watch some TV or something.

It must be hard on your personal life to be out touring constantly. Do you have a wife?

I’ve been divorced twice. Last time I was divorced in 1966.

Would you like to get married again?

I don’t think that anyone enjoys living alone. But as long as I’m traveling as much I’ve been it would be a useless situation to get married again. One of these other blues singers said I’m born under a bad sign. Maybe that’s it.

You mentioned that other blues singer. Are you related in any way to Albert King? Or to Freddie King?

No, not to Albert and not to Freddie. Although I wish I was.

Does being at Harvard really make you feel nervous?

[He gives a hard stare] I get nervous when you ask me questions. [Breaks into a smile] Yesterday Charles and me were talking about who would be the most nervous here. I think I won. That reminds me of a story which I’d like to tell you, if you don’t mind. Back in 1968 when we were recording “The Thrill Is Gone,” there was a lady that was handling publicity for me. She wrote up and prepared these questions and answers. At Channel – that’s a TV station in New York – there was a Chet Huntley lookalike. He was supposed to look at the sheets and ask me questions from there. Here I am first coming onto the scene. People have been seeing all these rock guitarists and here I am. Soon as we sit down and the mic goes on the air, he says, ‘What do you think of the Black Panthers?’ Oh my god. Now I used to stutter. And I don’t speak so fast. I said, ‘I don’t know that much about their platform, but I hear they’re feeding hungry children.’ ‘What about the KKK?’ Oh my god. ‘Well, I think that some of them probably think they’re doing the right thing.’ ‘What about the Kennedys?’ ‘I love them.’ ‘What about Reagan?,’ who was running for president back then. ‘Well, I think he’s a pretty good actor.’ That started me out.

What do you think of Reagan now?

I think he means well. But I’m not a Republican.

Just one more question and I’ll stop bothering you. Are you excited about the book Charles wrote about you?

Very much so. I learned a whole lot about myself reading what Charles wrote. I never, never dreamed when I was a kid of something like this.