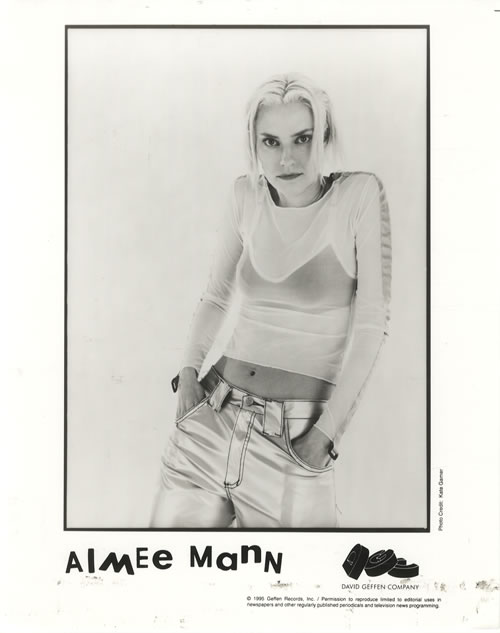

Aimee Mann

“It doesn’t even pay to sell out.”

January, 1996, in advance of the “I’m With Stupid” release and tour

By phone from her home in Los Angeles

I caught sight of Aimee Mann on TV last week. She was rocking out with Ted Leo, her unlikely partner in a new band, The Both. Singing and player a Fender bass, Mann pulled off a look few 53-year-olds would dare: black leather jacket, black hot pants, black fishnet stockings, sneakers.

The next day I tried to listen to The Both’s new record on Spotify but it wasn’t to be found, not there. Of course not. Spotify’s royalty rate is minuscule and Aimee Mann got fed up with getting ripped off a long time ago.

I first interviewed Mann in 1984 when she was the leader of ‘Til Tuesday and a rising pop star. By 1996, when the following interview took place, the 35-year-old Mann had been burned by the music business and wasn’t shy about condemning the rapacious industry in song and interview. She still hasn’t stopped griping about the mistreatment of musicians – to the point where you might accuse of her of having turned into a professional complainer. But by sticking to her convictions – and sounding (and looking) great while doing it – she’s gone from gadfly to indie rock hero.

Is L.A. home for you now?

Apparently so. I came out here about a year ago, but I go back and forth to a lot of places. I hardly live anywhere.

Do you spend much time in Boston any more?

I haven’t been to Boston in a long time, probably not in eight months. I didn’t actually move away. I still have an apartment there. I came out here to work and I ended up staying out here for awhile. Then I went to England, then back to L.A. Then my boyfriend [future husband Michael Penn] and I got an apartment together about two months. ago. But I still have a place in Boston that I’m paying rent on.

Do you plan to stay in L.A.?

I don’t know. I’m definitely spending a lot of time here ‘cause my boyfriend’s here and he has a child. He’s not going to move away. And it’s times like now that I don’t feel bad that I’m not in Boston. I like a little snow, but mountains of plowed black stuff….

Was the new album [“I’m With Stupid] finished a while ago while you were still searching for a record deal?

Yeah, a year ago. I finally got a deal with Geffen in August.

Did you originally think it would come out on a different label?

Well, this is a long tale, you know, of record company intrigue. When I was finishing the record I thought I had a record company when it was done. I found that I didn’t. But my contract was owned by the president of Imago [Records] and he [Terry Ellis, previously co-founder of Chrysalis Records] assured me that the record would come out as soon as it was done. But that just turned out to be a lie. He wanted to start another label using the contracts he owned. That began a long series of legal maneuvers until I wound up in a position where I convinced him one way or another to make a deal with Geffen to get this record out.

It seems like record company problems have become the story of your life.

Yeah, that’s how they are. That’s the nature of the game.

It started with ‘Til Tuesday being hung out to dry by Epic didn’t it, when they didn’t want to release your album, but they wouldn’t let you off the label?

People find it incomprehensible because it is incomprehensible. Unfortunately, it’s record company scenario number one. It happens to countless people at one time or another. Sometimes it goes on for a year, sometimes it goes on forever. Think of all those people you liked and then you start wondering, “Hey, whatever happened to so and so?”

What turned sour with Epic?

Years passed and they finally figured my career was ruined and there was no way I’d have a successful record with anyone else so they released me.

So they were punishing you for three years [after ‘Til Tuesday broke up and Mann wanted to launch a solo career]?

Because if they released me, they were afraid I’d go have a hit on another label. And they would not risk that. It’s totally sick.

They didn’t like your music?

That was part of it. But they didn’t trust their judgement until they got to the point that they thought no one else would like it either. It was a no win situation for me. I could have made records like Taylor Dayne, but the music I was making they weren’t interested in.

Was it that you were getting too acoustic, not pop enough?

At that point I was writing the music that would be on “Whatever” [Mann’s first solo album, released in 1993 on Imago]. They [Epic] heard the Elvis Costello song [“The Other End of the Telescope,” written by Mann and Costello; it first appeared as a duet on ‘Til Tuesday’s third and final album, “Everything’s Different Now” and later as the lead track (without Mann) on Costello’s 1996 album “All This Useless Beauty”]. They had access to it all, they just didn’t like it. It wasn’t commercial enough. They wanted me to be writing with Diane Warren, Desmond Child and Holly Knight — the hit doctors, the people who create artists like Taylor Dayne. As near as I could tell, that’s what they had in mind for me.

Did you find all this depressing?

Yes, of course. I still find it depressing. Even though I’ve lucked out for the moment and have a resolution to the situation and my record is finally coming out, I’m still in that world. Geffen at least has a policy of supporting the art portion of what an artist does. They don’t put out things without your knowledge or approval. Epic would remix a song and have it out on the street before you knew anything about it. That’s the kind of company Epic was. They didn’t give a shit. And it’s like what are you gonna do? Sue ’em? On your salary? Yeah, right.

Are you happy with Geffen or still wary?

Oh, I’m totally wary. It’s all fine so far. I like the people that I work with. I think the level of intelligence is a hundredfold what it was at Epic or Imago. But I’m wary. You have to be. You have to keep an eye out for trouble.

I hear Geffen plans on re-releasing “Whatever.” Are they looking to get it heard?

I think Geffen wants to have the catalog available. It’s nice to have it available.

Your song “That’s Just What You Are” appeared on “Melrose Place.” Did that give you a boost?

I don’t know. That was just kind of a one-off. It was a song I was going to release as a single and scheduling got screwed up and then someone asked if I wanted to put a song on this soundtrack. I wasn’t going to do anything else with it so at least it got a place on a record.

Giant Records put out the soundtrack and someone there lobbied for the song, which was bizarre because Giant was yet another label which wanted to sign me, was going to buy my contract from Epic, then negotiated an entire contract with me and backed out of it at the last moment. What’s more, it was a guy who used to work at Epic. There were a lot of good people at Epic, but they were under a regime that made it impossible to do any good for the world. And now one of them is at Geffen, Robert Smith, who turned out to be a totally great guy made very bitter having to work under the very oppressive, cold atmosphere that is the Sony way. Now he’s in a position where he can be supportive of artists and he actually is.

Did getting a song on the “Melrose Place” soundtrack have any effect that you could tell?

I never have any idea about that. Maybe people at Geffen saw it and said, “Oh, this is good, I wonder what her next album will be like?” They all heard it early on because there was an advance cassette when the album was done which was exactly a year ago. So they knew I was still making listenable music.

It’s ironic that you started out with a reputation as a commercial hitmaker in 1984 with ‘Til Tuesday but ended up with a reputation as a commercial failure.

It depends on the people around you. If you’re at a record company and they’re trying to second guess the market …the second ‘Til Tuesday album sounded nothing like the first. If you’re an incredibly stupid person, for instance, and you’re trying to second guess what the public will want to hear, the first knee jerk reaction is to say they want to hear exactly what we gave them last year because that’s what they bought. Common sense of course will tell you that if they liked something the year before and the year before, they’re probably ready for a change. But that’s not how they think. That’s why we have people like Bryan Adams who never go away. They just do the same sounding music for eons. Those records are virtually indistinguishable from the records they were making in 1984. The record companies love it. “Give us more of the same. More big snare drum, man.”

Do you feel as if your artistic growth has been held back by having to deal with people like this?

You start to do what you want to do in spite of these people. It’s the only thing you have. It’s not only what you ordinarily would be doing, but you have the additional sense of “fuck them.”

And that comes out in some of the songs in “I’m With Stupid,” where it seems like you’re looking for revenge.

To a certain extent. That’s what songwriting is all about. or at least it’s one thing it’s good for. When I was in that situation with Epic making that third [‘Til Tuesday] album, they were saying, “We can get you writing with songwriters.” And you kind of play along, like damage control, figuring you’ll do as good as you can. It’s probably not as interesting as what you’d come up with on your own, but you’re trying to play along. You still believe that these people have a clue and that they wouldn’t be fucking with you if they didn’t think it would result in something good. But as soon as you realize that they have no idea of what they’re talking about – and even if you wrote the most sell out piece of crap you could come up with – they still don’t necessarily have any intention of supporting your record. They could be on to the next thing. It doesn’t even pay to sell out. And once you realize that, the pressure is off to play along. You understand once and for all that no good can come of it and you can really write songs absolutely for yourself. You don’t have to worry about, “Well, I like this line but maybe it’s a little confrontational and I should change it for those guys.” Don’t bother with it. You do it exactly the way you want because at this point you’re resigned to nobody ever hearing it anyway. So you make music purely for yourself. And that usually is more interesting. It’s almost a good thing, in a sense.

Some people would love to have your problems. That is, getting well paid to deal with the record industry.

Bull. Let’s get one thing straight. It’s impossible to make money selling records. You will never do it unless you sell, I dunno, two million records. Let me get a second opinion. [Yells out to boyfriend] Michael! How many records do you have to sell to actually make money? A million? [Pause] Yeah, at least a million records. There’s no making a good living at it. It doesn’t exist. You either struggle along on little publishing deals or past windfalls or surprise visits from tooth fairies or you’re incredibly rich. Because out of the tiny percentage of what you make you’re expected to pay your record company back for the cost of making the record and the cost of the tour. An enormous amount of money. You pay it out of that tiny percentage, which they’ve already whittled down. And you make even less from CDs now, because CDs are a new untried format! Can you believe it? That’s a big argument when you negotiate to get the regular rate on CDs.

Do you see any skill at craft to admire in Diane Warren and other songwriters of her ilk? Could you have learned something from working with her?

There was no way it was going to happen. I was lucky. I went so far as to talk to her on the phone and there was a scheduling problem and I could report that back and get out of it. The fourth record was even more pressure. They thought the third [‘Til Tuesday] record was way too left of center. Writing a song with Elvis Costello was out of the question. Can you fucking imagine? That was out of the question. There was this woman the A&R guy really wanted me to write with, so I went out of my way and tried to make that situation. It was okay, but it wasn’t inspiring. So I tried to think, “Who would I really learn something from? Who is better than me? Who is a good person to write with?” But Elvis Costello is not what they had in mind. They took that as a slap in the face. It’s hard to comprehend.

After experiencing so much disillusionment with the music industry, have you now come to terms with it? Or would you like to be doing something else in five years?

I think I’d like to be doing something else. It’s too depressing to keep coming up against the same kind of problems when you see it’s just insane. You don’t like what a band is doing? Let them go do something else. Is it costing you anything? No. They’ll say, “Well, you owe us this money.” But of course you made them a couple of million dollars. Except out of that you only got a little money that you had to give right back. It would be nice if there was some kind of moral sense somewhere, but there’s not. It’s depressing. And it’s not even like there’s so much money in it. You can go, “Well, what the hell, I have a Mercedes.” I don’t even have a car.

No car? In L.A.?

Yeah.

So who is Michael? [Mann puts down the phone. She asks him if it’s okay to mention his name]

It’s [singer/songwriter] Michael Penn.

He’s one of those whatever-happened-to guys himself, isn’t he?

Three letters. R, C and A. He’s in virtually the same situation I had at Epic. A week after he was named best new artist at the MTV awards, a new president came in the company and cancelled his new video. How insane is that? But what are you going to do?

So why not just go out with a guitar and become a folk singer?

For me, the live thing has become an adjunct. It was never the big thing for me. Writing music is the big thing. I can see myself writing music for movies one day. You get paid for that.