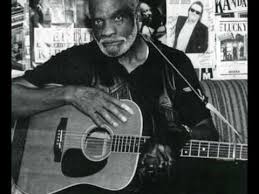

Ted Hawkins (1994)

“….I’m wringing wet with sweat, my throat’s on fire and my hand is aching. But I had to keep going…”

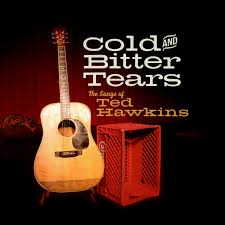

“Cold and Bitter Tears – The Songs of Ted Hawkins” is a tribute album boasting no celebrity names. James McMurtry, Kasey Chambers and Mary Gauthier are probably the most recognizable of the Americana and country artists on this new CD. But then Ted Hawkins never came close to celebrity himself, except to those who heard him on record or on stage – which in Hawkins’ case was most often in the open air on the beachfront sidewalks of Venice, California.

Original Interview Audio:

Even if you never heard (or heard of) Hawkins, his songs sound like you’ve heard them somewhere before. They’re strikingly original, but also timeless, in the way of folk songs that stick around not only because of their music and lyrics, but because they speak truth simply, directly, powerfully.

If you want to put Hawkins in a box, he could be classified as a folk singer. His first album, “Watch Your Step,” was released in 1982 by Rounder Records, which at that time specialized in folksy roots music. But Hawkins’ voice also won him comparisons to Sam Cooke and Otis Redding; several of his songs might easily have scaled the country charts had a George Jones chanced to find them; and his Mississippi upbringing and hardscrabble itinerant life befit a bluesman.

Like others who fell under the spell of Hawkins’ two Rounder albums (the second, “Happy Hour,” came out in 1986), I was amazed and gratified when I learned he’d been signed to a major label deal and Geffen Records released “The Next Hundred Years” in 1994. I was happy for Ted and happy for myself when he went on tour and I got to speak to him in advance of a performance in Somerville, MA at Johnny D’s on May 19, 1994. Hawkins the conversationalist proved no different than Hawkins the musician: painfully, touchingly honest.

Hawkins did not get to enjoy his late-in-life career breakthrough for very long. On January 1, 1995, a little more than seven months after we spoke, he died of a stroke at age 58.

May, 1994

On tour, in a Dallas hotel, by phone

[Photo taken at Johnny D’s, Somerville, May 1994. Note the black leather glove Hawkins wore on his left hand while playing guitar.]

I know you were living in England for several years before you came back to the U.S. in 1990. Why’d you come back?

I was having visa problems and they deported me. My time ran out.

Did you want to stay there?

Well, England is a pretty good place. It’s just that I had a lot of bills back home and I hadn’t seen my family. I had to get back home.

Were you a success overseas?

I was working regularly. But I didn’t become a success because it’s not what you know, it’s who you know and I didn’t have the proper people working for me that I have now to build my image up in the eyes of the public. I went to Los Angeles, grabbed my guitar and went back to Venice Beach to try to make money and make ends meet. I left Venice Beach and went to the promenade in Santa Monica. I was singing at a place called Give Me Shelter, one for the homeless. There was somebody in the audience, a disc jockey named Tony Berg. He’s now affiliated with Geffen Records. He was enthusiastic. He came to my dressing room and gave me his card. We talked business over dinner, me and him and Todd Sullivan, an A&R guy at Geffen. The week after Tony Berg gave me his card, Todd Sullivan came by without knowing that and dropped his card in my bucket. So it wasn’t no mistake. All three of us wound up sitting down at the dinner table somewhere in Hollywood talking business.

[Above: “Strange Conversation,” lead track from “The Next Hundred Years”]

You’ve had records before that came out on Rounder, but this one [“The Next Hundred Years”] is your first for a major label. Is that something that’s significant for you?

I’m very, very happy it’s on a major label. I’m now on my way in my old age. I’m glad that whoever is sending down the blessings waited until I got some age on me and learned some sense before he gave me something. When you’re young you can’t handle it. You wind up shooting yourself in the head or whatever.

Did you blow some opportunities in your career?

I never had opportunities to get nowhere. Musically, I had been trying. I had many, many doors slammed in my face. I was put on the back burner, people not wanting to take the risk because they didn’t know enough about me. It’s hard to get a record deal. I used to sit on top of the record companies’ steps hoping that someone would pass by and hear me and take me in there. They passed by but they never did stop. I went to Capitol Records and sat on the steps. I did that daily for a time. But I never got inside.

So as I understand it, your first started recording with Bruce Bromberg in 1971, but the recordings you made didn’t come out until “Watch Your Step” wasn’t released until 1982.

Yes. That record label being so small and financially crippled with nobody to help them. You have to have a little money. They just didn’t do nothing. One thing that presented itself was a record company in London called Windows on the World. They leased it to Windows on the World and I think they have it now. They weren’t doing too much either.

On the cover of “Watch Your Step,” there’s a picture of you standing in a prison courtyard. What were the circumstances behind the photo shoot?

Well, I was told by my colleagues not to talk about that. It brings back bad memories. It hurt me so much. I’m trying to crawl out of it now and go on with my life.

[Above: “Sorry You’re Sick,” a Hawkins’ classic from “Watch Your Step.”]

You’ve been a street singer in Venice for a long time. Did you like doing it?

I didn’t enjoy it. Many, many days I had to eat a lot of sand. The wind blow sand down my throat while I’m trying to sing. It comes so fast I don’t get a chance to stop it. People are constantly passing by. You have to sing like there’s someone after you to make them stop. Now you got to hold them there. They passed by many guys who are singing their hearts out and they didn’t pay them no attention. But I finally got them to stop. I closed my eyes and didn’t care if they stopped or not and sang like there was something after me. I open my eyes and there they stand. But by now I’m wringing wet with sweat, my throat’s on fire and my hand is aching. But I had to keep going, from ten in the morning to six in the evening, stopping only to have a sip of coffee every now and then. I wound up with a nodule on my vocal cords and had to get an operation. My trouble is because of the fact that I don’t have an education there was nothing else I could do. Once upon a time a long time ago I could wash dishes and they wouldn’t ask for no high school diploma. Now they ask for it even for washing dishes. You can’t do nuthin’.

When you were growing up in Mississippi you met Professor Longhair. Was he the one who got you interested in music?

I met Professor Longhair in the reformatory school for little bad boys. I was about 12 years old. He used to come by and talk to the boys and tell them to be good and give them all kinds of advice. He saw me in a big crowd of children way over on the campus. He went over to check what was going on and there I was in the middle singing to the children. They used to like to hear me sing. He told Ms. Williams, and Ms. Williams, who was G.W. Williams wife, these two people were the head of the school, Oakley Training School in Mississippi, about 24 miles from Jackson. It’s co-ed now, but back in those days, 1949, it was boys. One dining room and two barracks made of brick, one on each side of the dining room. I can see it now. I can see the bell that they ring for each function that we would do, to eat, to go to work.

I used to just sing to the other boys. They used say, “Sing, Ted, come on! Sing, Ted!” And I beat the hambone for Professor Longhair. The hambone, you pop your mouth. He like that. He took me to Ms. Williams and him and Ms. Williams thought of a song, “Somebody’s Knocking at Your Door.” He played the piano. Ms. Williams played the piano, but this time they took me to Jackson and he played the piano. He played piano pretty good. I was standing on the stage behind the curtain and somebody called my name to come out. I couldn’t move. My little knees got weak. I almost fell. I almost started crying, I was so scared my little heart almost jumped into my neck. Ms. Williams gave me a push and I went on out there. If she hadn’t of given me a push I wouldn’t be singing today. That push made me get over that stage fright, but I was still scared – those folks had eyes and they would look at you with ‘em. But when I finished singing everybody rushed to the stage and picked me up. Everybody was trying to tell me how good I was at the same time. They was kissing me and hugging me, they had me way up in the air and everybody talking at the same time. I’d never known such excitement. I can almost relate to the way Michael Jackson feels when they do that to him. I wanted more of that, but I didn’t know how to go about getting it. I never did get that again. That never happened anymore. But people was enthusiastic.

Did that inspire you to pick up guitar? So that you could accompany yourself?

Yes, I liked that feeling. It’s a feeling of power, a feeling of power. A feeling that you giving people what they want and you doin’ that for them. This would give me a good feeling. Later, when I was on Venice Beach, a lady whispered in my ear, “Don’t stop singing, you’re healing me.” I couldn’t look back because I was deep off into what I was doing. There was so many people standing there you can’t stop. If a mosquito is biting you you let him eat. If you stop to try to hit him or knock him off, the folks will wake up from the stupor you put them in and say, “Oh, what am I doing standing here?” and they leave. So I had to keep right on going, keep right on going. And they there, they love it, they swooning. You can’t break that. If you break that they walk away. The lady say, “Don’t stop singing, you healing me.” Don’t you know that if I thought just a little bit I could do that I would go to the utmost parts of the hospitals and do it free. If I just thought I could that for somebody. I don’t know if she telling me the truth or not, but she sure sound serious. “Don’t stop singing, you healing me.”

I have found that there are people that have stood before me, many, many thousands of people have stood before me at Venice Beach, and they’re all now scattered throughout the world. They know about the CD and they hope I make it because they knew me then. They think I deserve it. Many thousands of people have stood before me and stood under the sound of my voice. I’ve seen tears, I’ve seen smiling faces, I’ve seen ladies that lay on their lover’s chest and cry while he soothes her and I’m singing, “All I Have to Offer You Is Me” and “Bring It On Home to Me.” I love tearjerkers. We don’t have enough tearjerkers left these days. Everybody’s clowning, rapping, and nobody’s serious. It’s time to be serious. We don’t have enough love in the world anymore. We have to be serious, especially in singing.

[Above: Ted sings “All I Have to Offer You Is Me,” originally done by Charley Pride]

Are you hoping that your street singing days are over now that you are with a major label?

I hope that I won’t ever have to return to Venice Beach any more, because I have colleagues now that are 100 per cent in the Ted Hawkins’ corner. When I went out to Venice Beach once since I been affiliated with these people, Geffen say, “Don’t do that. You don’t have to do that anymore.” I say, “Why not? Sometimes I feel like going out there.” They say, “It don’t make sense, Ted, for us to charge people money to buy tickets when all they have to do is go to Venice Beach to see you sing.” I said, “Oh, you right, you right.” But if you get a hog out of the hog pen and wash him up and put perfume on him and put a hog suit on him, well, he’s still a hog. And he must never forget he’s a hog.

So you still get the urge to get out there?

It’s a bittersweet thing. I think about it back there and I swallow hard. I think about those days. It’s a bittersweet thing. You’re down on your luck, your rent is due, you have to pay your bills. Your hustling and people pass by and throw a dime in there, thank you, a penny, thank you very much. You singing….there are movie stars that would jump for a script where they poor and they live in a poor neighborhood and they’re holes in the wall and they down on their luck. They jump and race for a thing like that though they millionaires. What is it? Why?

Your two Rounder albums are now available on CD. With Rounder based in Boston, did you ever have a chance to play Boston before?

No. All these places I been stopping at now, it’s my first time, except for New York, Chicago and Philadelphia. When I went to those places I went there as a bum. There wasn’t no happiness at all. I was trying to keep body and soul together. That’s why I like that song Bruce Springsteen put out, “The Streets of Philadelphia.” Oh man, you should see that.

Do you like it that you’re now playing indoors in clubs?

No matter where I play it’s not that hard. When I was on Venice Beach I didn’t know it but I was training for the main event. I was learning to stick with a song, to sing hard, to duck, weave and bob. The trials and tribulations come to me, all the airplanes flying overhead while I’m singing, people screaming and hollering and walking by me, dogs barking, and I’m singing away. So this little stuff here is nuthin’.

The song “Big Things” makes it sound like you’re eager to accomplish a lot now.

I was thinking about me when I wrote “Big Things to Do.” Every word is me. Because it’s the truth. I do have big things to do and I don’t have a long time to get it done.

So capitalizing on your success and making something of your career is important to you?

I’m going to make the most of it. I’m not going to do nuthin’ to mess this up.

[Ted sings his prophetic “Big Things.”]