May 1992

Augusta, Georgia

The sweetest words I ever heard an editor utter:

“How would you like to go to Georgia to interview James Brown?”

A week later I stepped out of the Augusta airport into a perfect Deep South day in May: bright, sunny, mid-70s. I drove my rental car via the Bobby Jones Expressway to my lunch destination, Sconyers Bar-B-Que, as upscale a barbeque joint as you’ll find below the Mason-Dixon Line. When I was done stuffing myself, I still had several hours to kill before my late afternoon sitdown with the Godfather of Soul. I passed the time cruising around Augusta, checking out the sights and listening to local radio, which boasted two stations playing killer gospel. I drove by the leafy Augusta National Golf Club, where I am fairly sure JB was never a member.

Why had my editor at the Boston Herald sent me to Georgia?

Not because he loved funky music. Or that he was willing to blow a chunk of his budget on this jaunt because a one-on-one in-person interview with James Brown would be a dynamite cover story for the paper’s weekend entertainment section, especially coming a year after Brown’s release from prison for aggravated assault and leading the local police on a high-speed, drug-fueled car chase. No, my editor was simply following orders from on high: the Herald had struck an agreement to be one of the sponsors of the annual KISS mega-concert at Great Woods. Part of the payback for the Herald providing copious in-house adds for the show, the radio station had arranged for an interview with the headliner.

I don’t know what I expected James Brown Enterprises to look like, but the funk-free reality was a surprise. Soul Brother No. 1’s office was located in an upscale suburban shopping area, part of a collection of well-maintained single story buildings occupied by doctors, dentists and accountants. A receptionist asked me to follow her to Mr. Brown’s office. We walked down a long, narrow carpeted hallway lined with framed gold records and entered Mr. Brown’s lair.

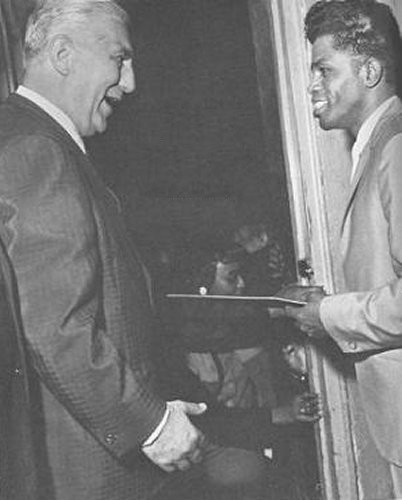

Mr. Brown – as all his employees called him and as he preferred to be addressed – jumped up to shake my hand. He was thick and stocky and he exuded vitality and power. And he was dressed for the occasion. Not for this specific occasion, an afternoon interview with a journalist, for which nothing the least bit formal was required. No, he was dressed for an occasion. A photo session, perhaps. A meeting with the president of his fan club or the president of the United States. A show at the Apollo. Dude looked bad. Slick black shirt, a carefully knotted patterned tie of the palest purple, black brocade vest covered with gold butterflies, perfectly pressed black-and-white houndstooth pants, glistening shoes. And that famous head of hair. Lustrous, black and beautiful, every sweep and curve perfectly in place, an architectural wonder. Even the man’s skin glowed. His appearance said, loudly and proudly, “I am somebody!”

My encounter with this legendary, monumental performer came back to mind last week when I was watching “Get On Up,” the new James Brown biopic, produced by Mick Jagger, among others. Chadwick Boseman, who delivered a noteworthy performance portraying Jackie Robinson in “42,” is not a dead ringer for JB physically, but he does a fantastic job of capturing his singular energy and drive – and his spectacular dance moves. Every musical scene in “Get On Up” delivers a thrill (with Boseman lip-syncing Brown’s original vocals to re-recorded tracks), as this highly selective sampling of the Godfather’s output inspires renewed appreciation of his musical genius. I won’t review the movie here, but I highly recommend it, despite some flaws. The brilliant opening 15 minutes are laugh out loud funny and worth the price of admission, as is the recreation of James Brown and the Famous Flames surpassingly strange appearance in the 1965 Frankie Avalon teen flick “Ski Party” – so bizarre that I can’t resist sharing the clip from the original movie.

After he greeted me, Mr. Brown settled into a large swivel chair behind his oversized desk.

Before I could ask a question, he began to talk, immediately establishing who was in charge.

For the next hour he held forth, while I listened, nodded my head and interjected the occasional question.

“Thank you very much for coming. We’re looking forward to a very big show in Boston. It’s a very worthy thing. I’m excited about it because I like to be a part of anything that’s going to be good for our country. The leaders need to show some interest in the kids. It’s getting worse everyday, y’know. Music is probably the best way in the world to reach some of those problems.”

“Some of those problems.” There was no doubt in my mind that Mr. Brown was referring to the Los Angeles riots, which were on everyone’s mind having occurred only a week earlier, from April 29-May 4. Mr. Brown had etched his name in Boston history almost a quarter a century before when riots broke out in cities across the United States on the night Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. After some tense negotiations with Boston mayor Kevin White and others, Mr. Brown not only went ahead with his scheduled performance that night at Boston Garden, but he allowed the show to be broadcast live on WGBH, the local PBS station. No one knows how many people who otherwise would have been out in the streets stayed home to watch the show, but the gambit worked. There were no riots in Boston.

“We’re working on a show for (the L.A.) area that’s going to be very good,” Mr. Brown said when I brought up his historic Boston performance. While no longer the major cultural figure he was in the sixties, Mr. Brown seemed to believe that he could play a role in alleviating racial strife in L.A. and beyond.

“Mayor (Tom) Bradley is a good man. He’s aware of the problem. I think Mayor Bradley has handled things very well. He’s never gotten away from what he thought was right. He was somewhat disturbed with the courts. It probably could have been handled a lot smoother, a lot more sophisticated, a lot more real than just saying the police was right. It’s kind of sad that all those people lost their lives because of one bad decision, something that we should be a part of. We’ve had enough of this mess. I’m tired of it. I think the average American is tired of it. We’ve got to bring our family squabble to an end and go on with our lives. All the opportunities are there. We have to take advantage of them. I thought the Kennedys and Dr. King getting killed was the worst thing that could have happened to our country. Here we are again, the same kind of mess. It just don’t make sense. I do everything I can to make good relationships among people throughout the world. And I should have started at home.”

To my surprise, Mr. Brown started to talk about his own troubles with the police. I’d been nervous about the necessity of bringing up his 1988 arrest in South Carolina and resulting incarceration, figuring these might be sore subjects Mr. Brown would not be eager to discuss. But I had to ask. I could not ignore what had been the biggest story about him in recent years. Now he had saved me the trouble by more or less equating his situation with Rodney King’s.

“The same thing happened to me three years ago. I played it down. My attorneys wanted to know why I wouldn’t fight it. I knew that [the police] were wrong. And they knew that they were in the wrong and most of the people did. But they stay with law enforcement. Because we have to have law. And this is right. If we find a couple of bad apples, you get rid of them. You don’t spoil the barrel. I’m still pro-law. I’m pro-security. I’m still pro-protection. And also anti-harassment and anti-incompetence. And that’s what this is. It’s incompetence. Any time nine men can’t subdue one, then what do they need guns for? Nine man gotta be able to handle one man! One big man can whup five good men? They can be little men but he can’t whup five. And they had nine! That’s a joke. A real joke. It’s caused our country a lot of grief. A lot of embarrassment. All over the world, policing and doing things, that should represent the free world, free enterprise, an open country, an evolved country, a humanitarian country, a religious country. And then here we wind up in our own yard with more trash than you can find in another person’s yard. South Africa is even trying to come out of their act and get it together. And here we are going backwards. How dare we tell them what to do ever again. And China and Iran? Please don’t give us no advice unless you’re going to take it yourself first.”

Then Mr. Brown veered in a different direction. His new music could heal America, heal the world, if only people would listen. Mr. Brown believed he had lost none of his musical and cultural clout.

“But on a good note, the music right now is going to answer more questions than anything else. Happy music brings happy reactions. And that’s what we need. We need happy music right now. We need it very bad.”

So, I asked, do you have new music in the works?

“We have a single on [the new album] ‘Love Over-Due’ we’re gonna put out. We had two good singles that should have gone, but they weren’t ready to hear good music and good messages. ‘We’re tired of standing still and we got to move.’ It went past them. I came up singing ‘Put A Little Love in Your Heart.’ They didn’t hear it. So now finally I’m gonna tell them to dance. Get happy. We’ll start in Boston and then take it across America and spread it around the world. I’m gonna do another album, probably in September. And I’m gonna be conscious of the lyrics to be sure that they’re saying something. I’m not gonna do the boy meets girl thing. I’m gonna do some dancing, maybe one long song, but I really want it to be something that identifies with our environment and to lead us out of this turmoil into something positive. I want to give a message to young people. To be dumb is to be numb! You see what I’m saying? To go ahead, that’s the idea. To try to make them turn out right. You didn’t walk in here with a cap turned backwards, your pants turned backwards….You don’t go to church wearing your cap back. But where are all your morals? And no one is teaching them. And when a kid can sit down and hear a four-letter word on television. Or when a person record a song and go say, ‘Mama, this is what I recorded.’ He’s ashamed to sing it. No one is going to curse and blaspheme in front of their mother and dad. Kids don’t know. They just don’t know.”

Live performance of “(So Tired of Standing Still We Got to) Move On,” the lead track from “Love Over-Due”

Is he disturbed that young performers who admire him and liberally sample his work are not making positive music?

“Well, there are some songs with the rappers and the hard rocks that have to be changed. I think the videos are terrible. They make a big thing out of it. People doing very suggestive things. They ban it on television but they play it long enough for you to see it. People doing very suggestive things. They walk up there with their pants hanging down and their butts out. This is a joke. What are we talking about? Years ago, you have everything out but your butt and your privates. Now they pull their privates out and hide the rest. I don’t understand this.”

It’s hard to get worked up over dirty lyrics and baggy pants with the L.A. riots still fresh in everyone’s mind. Didn’t the riots, I ask, have more to do with racism than suggestive music?

“No, it was not the suggestive music,” Mr. Brown allowed. “But it was an enhancement of the wrong.”

And then he is off on another lecture/rant. He bursts with frustration that others, young people especially, lack the drive he had – and still has.

“First, you must educate people. They can’t get jobs even if they’re available because most of them are not qualified. Now we were mandatory. You had to go to school when I was a kid. Of course I didn’t go any farther than the 7th grade. But school wasn’t as sophisticated as it is today. Today you get a high school education and a trade. I never condoned getting out in the 7th grade because it was a very dangerous thing, a very critical thing for me, and I was lucky enough to get my talent going. Let me tell you, I was a fellow that had three professional fights. I had a chance to play professional baseball. I was determined to make it and I wouldn’t let nuthin’ stop me. I’m 59 now and I can outdance most people at this stage. Because I want to be somebody. And that’s what I challenge to the young people today. Want to be somebody! Want to succeed! Want to overcome the problems that are out there! Make yourself important! Make yourself involved! That’s what I’m about. That’s what I stress all the time.”

Mr. Brown rolled on, revealing himself to be more than a self-starter and a believer in self-empowerment: He is a utopian idealist.

“I also feel the conglomerates need to try to minimize some of the profits, take their windfalls and try to put it back into programs that can endorse better living, quality living, and make people want to have something. The movie people should deliberately change the mentality of the people. They’re an endorsement of crime, murder, killing, drugs. Let’s endorse schools, the football, the basketball. Let’s endorse clean music, clean living. We won’t have to use the word right or wrong no more. Soon we’ll just use the word destruction. Because that’s what it’s going to be. There no right and wrong no more. We’ve got to try to find that again. People cannot do it by themselves. Because we’re into it real deep. They’ve got to have training. They’ve got to have the major conglomerates, the Fortune 500 people, come back in and get involved. One thing you’ve got to remember: that if urban America has a problem, then next suburban America has the problem and after that it’s rural America. It’s one-two-three A-B-C. That’s how it goes. When that’s the story then sitting back on your fat tuchas is gonna get you in trouble. You’re in major trouble because you can’t leave your home. Or look at how Howard Hughes was living. God forbid, the man couldn’t trust anyone no more. And this is what’s happening to the fat cats. They’re afraid to trust no one and they’re not doing what they should be doing.

“You know when you get away from basics you’re blown away. Everybody in this country got some kind of religion. A hundred per cent of us got it somewhere in our background. It didn’t fail for our forefathers. So it won’t fail for us. The only time we can remember is when our democracy will get away, when some regime gets away from the basics of the church. Look at Russia. They’re churchgoing people again. Now they want to live. They’re smiling again. They don’t have to look straight ahead and be afraid to have an emotion. A lot of countries have gone through that. But this is the first time that America has gone through it in my 59 years. Even in tough times we always came out of it. But this time we can’t come out with everything being wrong. You understand me? They started with the churches and they went through everything we put a value on it. Now we have to say, ‘We’ll show you. We’ll be back’.”

Did he harbor any resentment, any anger, at the authorities after what he maintained was his wrongful arrest?

“I don’t have bitterness. I have frustration. You come to talk to me and if I disrespect you, treat you with another kind of attitude, you say, ‘I came to see this man – forget he’s a star, forget anything – and the courtesy of a human being, he ain’t showed that.’ See, I have to show that even if you don’t write a good story. I may not like what you write. But I still feel that I have an obligation. With integrity and dignity and love. Get away from the religious side, it’s still there, the love. I feel like Will Rogers. I never met a person I didn’t like. I see people. I don’t like their ways, but the person themselves, I can’t dislike them. Because if I dislike them there’s no reason for me to go to church. There’s no reason for me to say I love God if I dislike ‘em. I can’t think like that. But a lot of people, I don’t like their ways. If I’m gonna get myself involved around you, I’d like you to have better ways. But other than that, if we feel that God is always there and he’ll help us if we give ourselves to Him, then we can do the same. I’m not gonna hold bitterness against our country when it’s one or two people. I’ve got relatives who didn’t visit me when I was in trouble. I’m not gonna be angry with the government when these are people who have been with me my whole life. When they thought it was over they didn’t show no more.”

“So if I understand you, there is injustice – but you do not deal with it by getting angry or depressed?”

“That’s right. Yes, there is injustice. Oh yes. Had I magnified it, god forbid what would have happened. See, I was fortunate enough to be one of the people who could help quell the riots in ‘68. And also one we had here locally in ‘70. And that’s what is important. Somebody who will lend themselves to the problem and be the solution rather than be adding to it. Two wrongs don’t make a right. The ABC’s of this problem is what caused the problem. It just got down later in the alphabet and this thing triggered and that thing triggered and there it was. We cannot let a hungry animal guard the meathouse. If a person is in the dark and the light comes they take advantage of it. These people need an education so they can protect themselves. If there was a job out there, 75 percent of them couldn’t take it because they couldn’t handle it. You gotta go back and teach ‘em.

“I had a manger once. His name was Mr. Benjamin Bart. He helped me more than my own relatives did. He helped me get ahead. I stayed with him a good while. He said, ‘Jimmy, if you’re gonna live with ‘em, you gotta teach ‘em.’ He said, ‘I admire you for being around, keeping the same people, talking to them.’ He said, ‘Jim, I respect you. It’s a hard job. But if you live with ‘em, you gotta teach ‘em.’ He was admiring me because I was trying to take raw people, like myself, and try to help cultivate them. And use their energies. It’s like what you do with your kids. You mold them. And it’s hard to mold a person. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks. But if the dog is hungry, he’ll try to learn ‘em anyway. We’ve got to realize we’re hungry. We’ve got to realize that we can’t handle it and we can’t take it. It don’t give you a right to take it. If you don’t earn it it’s not yours. It’s not the man next door. If you figure you don’t get what you want, then deal with it. Massively get in the street. Express your views. Raise you signs. And they’ll get conscious. Cause they know they won’t get elected. But you got to go that long way.

“Now I’ve not always had that much patience. If a man sticks a gun on me and I get a chance to grab it and save my life, I’m not going to call my congressman. But by the same token, if I can talk him out of it, I’ll talk him out of it. Play some politics with him right there. Listen mister, you want this suit, take it. But I want to live.”

“Did prison make you a different person?”

“A different person in the sense of understanding that we’re in trouble. If you take a man who’s making 500 dollars a year and he’s taking care of a couple of kids and he’s making it – I don’t know how, but he’s making it, plus he’s paying tax out of it – and you put him in jail for something as simple as DUI – you can take his license, do other things to take him out of commission other than put him in jail – you taking a 9500 dollar man and taking him out of the tax base and it cost 20,000 to put him in prison. And you have to build more prisons instead of building schools. What is this? This is stupid. You could be building schools, but you’re building prisons. No, you can’t do it that way. And all the ones that are gone to prison, their kids got kids coming and there are things happening to them.

“When I came along with a 7th grade education, it was strong. It was like a high school education today. And menial jobs were there. I could grease a car, wash cars, mow lawns, deliver groceries on a bicycle, work on an ice wagon. Those jobs were there. I could cut ice. I shined shoes. The jobs were there. You could be a bellhop. They were there. They are not there now. And the people that have those jobs now, they’ve got a high school degree. They’ve got training. Now some fellow comes along without a high school education he hasn’t got a chance. I’d like to hire him but I can’t. I’d rather give him a few out of my pocket. But I can’t hire him because he ain’t gonna function. It’s impossible. Because he don’t know what I’m talking about. At least get a concept of what can be a danger zone. He don’t know. When the news comes on, he just switches channels because he wants his ‘Gunsmoke.’ But he’s living in the Western days and he don’t know it.”

“When you got out of prison, did it make you…..?”

“When I got out everybody realized that James Brown had been a good guy and had been taken advantage of. They took four fortunes from me illegally. I’ve never owed but less than three hundred thousand dollars in taxes in my life. I come out and the man says I owe 15 million. For what? It’s like they told me to plead guilty to a case where I’m sitting there still while they shoot my truck up and they say I’m aggravating it. I’m aggravating it sitting there talking to another officer? They laughed at it here locally. But abroad they had to dramatize it because they didn’t want it to look like it was that bad. But then here, God works in mysterious ways. They put it on camera so they couldn’t back out of this one. See, suddenly we have to address those people who with a gun and a badge are terrorizing our country. Meeting the drug man. I know the situation where the fellow said the police told him, ‘Look, put the drugs and money on the car.’ He said, ‘Are these your drugs. He said no. He said, ‘Then the money must be yours, right? Right. You heard about that, didn’t you?”

I’m lost. I’ve lost the thread of whatever it is Mr. Brown is talking about. I’m hoping when I play back the tape that it will make more sense. But at the moment, I just nod my head in agreement. It takes a lot of concentration, a lot of energy, to be on the receiving end of Mr. Brown’s impassioned oratory, which for the past forty minutes or so has been directed solely at me, the only other person in the room with him. In addition to the challenge of following his train of thought, the man’s voice is a deep grumble, the words gushing forth in a sometimes hard-to-understand torrent. Meanwhile, Mr. Brown keeps rolling.

“You’ve got to love this country it you’re going to protect it. You’ve got to love humanity if you’re going to serve it. I saw a nice gesture just the other night. A fellow was a gambler and a hustler. He was going across the street and there was a suitcase on the ground a fellow had walked off and left it. He opened it up. It was full of money. Now he’s a hustler. But at that point he was converted. He said, ‘I gotta catch that man with this money. I can probably get a reward.’ That’s a lot of decency there. Because he could retire from hustling with that money, but he didn’t want to take what wasn’t his. In the con thing, he outsmarted a man. But this was different. I can understand that. The con is wrong too. You make a career out of taking from the less sharp person. But if you have that sharp mind to be a hustler, you can take that same mind and become a really fantastic leader. It shows you there is respect and integrity in everyone. So we just have to work on that and we can come out of this thing.”

“Was prison any kind of vacation for you? Or are you going to try to slow down now?”

“I have got to slow down. I’m very busy now, but I’ve got to slow down. I’ve got to come off it. Everybody wants me and I thank God that they want me. But I’ve got to slow down. Because my value is being seen and motivating young people and being a live, walking person. That’s more important to them then me being gone like Elvis. I wish Elvis was around today. You know why? Because it would be a lot easier for me. I wish Otis Redding was around. Sam Cooke. Jackie Wilson. The Mamas and the Papas. Mama Cass, I mean. I felt it real bad when Freddie Prinze left us real sudden. That was bad. He represented the Hispanic people in their hard fight. Everyone wants to be represented. That takes a lot off your mind, off your back, opens a lot of doors. Nobody has a monopoly on doing bad. A lot of people are doing bad. But the thing about it is the black people have a monopoly on uneducation. And as long as it’s gonna be that way they’re not going to succeed as a whole. Not even 75 percent whole. If you can’t know it, you can’t do it. It all comes down to education.”

No doubt Mr. Brown is a bit of a megalomaniac. He sees it as his personal responsibility and within his power to heal the problems afflicting our country and the entire world. Is it hard, I asked, to be James Brown when so much is expected of him?

“Yes,” he answered. “But I think I have a chance to do what I’m doing and perform and bring back those good memories and it’s a revitalization plan for myself. When I see their face, I feel good.”

“Do you continue to live here in Augusta in order to stay close to your roots?” He shoots by the question to contemplate his own achievements and the great burden success imposes on him.

“Today I was with people that helped me to get started. And the James Brown the world knows [is] bigger than most people that ever been in show business. Contributed more singlehanded than any composer as far as the 20th century is concerned. Style. Attitude. Thank God I was able to do that. Last night I was sitting with the wife of Malcolm X. Three months ago I was sitting with the wife of Martin Luther King and talking. All of them totally endorsing James Brown. That makes me think I have an obligation. The obligation is greater than me and you. It’s the future of our country. The future of humanity, that you can add to in a positive way.”

I attempted to approach his relationship to his hometown from a different direction. Did his arrest and imprisonment make him want to leave this part of the South? Did he now fear the police?

He scoffed at any such notion.

“That isn’t going to bother me. I guess they’ll do what they’re going to do. I can’t stop that. L.A. wasn’t any better. Boston isn’t that much better. New York. We got to educate everybody. That’s what’s important. That we work together. What’s happening in Boston with this show is the best start. Look out for the children. Create a good impression. We need to do it in the worst way. We trying to do it in New York. We trying to work out something in L.A. We just had 7,000 people in Atlanta in three days in the street and not one bottle was broken, not one can was left outside. It was so amazing. There’s an old fellow who makes artifacts out of old cans. He said he had to go to the garbage cans to get them, there weren’t any on the ground. The pride was there. And I love that.”

“So you’re a believer in the power of music?”

“I believe in the power of God. ‘Cause God is music. He is love. ‘Cause when it comes out with good music, wholesome music, you get a wholesome reaction. When you have violent music you have a violent reaction.”

“Are you bothered when you see some of the people currently making it big in music who don’t show much evidence of musical talent?”

“I feel sad most of ‘em can’t play a musical instrument at all. I play seven instruments and I never had the chance to go to music school. But my advice to all young people is learn to play one instrument and you’ll get a whole different vision of what you’re about.”

“Does it make you angry to see someone make millions without a lot of talent when you had to struggle so mightily?”

“God works in mysterious ways. They find out that the rappers that sample my stuff, it was always there, but they never enforced the law. Now they’re going to enforce the law and I’m going to get paid. Because the rappers don’t know that they’re doing it. They’re just paying homage to you. But the record companies know that there’s a copyright law and if it has your name on it they’ve got to pay the price. So I’m just waiting. If I got 500 dollars a day or 50 million, the first thing I’d do is go to the school I was going to and turn it into a music school right in the middle of the ghetto [in Augusta]. And I’d do it in a lot of other cities. Because we see where the uneducated people have to go to music or sports. We need sports where you can come off the streets and get into major sports as well. Because a lot of people come off the streets and they’re just fantastic and they’re just there. They can’t get utilized. You can get people out of sandlot. I know you got a problem with the NCAA thing, but you got someone who didn’t get to go to school they should be able to go and use that talent. You know what that is, don’t you? It’s monopoly. Every man, according to the bible, has a right to the tree of life.”

“Are you a churchgoer?”

“I go as much as I can. Right now I have to go see my dad.”

Mr. Brown rose out of his chair. My time with him was up. But not before another thought.

“I know my name, my talent, reaches worldwide. But I don’t want to be James Brown the character. I want him to continue doing the good he does. but I would like him to be a little more out of the limelight. I have enough limelight. When I walk out on that stage, I want to do my shows. First in Boston. Then I’ll go out to California. Then I’ll rest a couple of weeks and then go do Europe. I want to address some of these issues and hopefully be of help.”

A beaming Mr. Brown showed me to the door, radiating absolute confidence that he had delivered another in the long string of the knockout performances that defined his life.