David Bowie (1995)

When liver cancer killed David Bowie on January 10, 2016, he had made sure the world would be thinking about his art as well as his death.

When liver cancer killed David Bowie on January 10, 2016, he had made sure the world would be thinking about his art as well as his death.

Original 1995 Interview Audio:

His musical, “Lazarus,” opened off-Broadway on December 7; his final album, “Black Star,” appeared two days before he died; in between the show and the album, he released a single, “Lazarus,” which pointedly opens with the words, “Look up here, I’m in heaven” (the New Testament’s Lazarus, if you forgot, was brought back from the dead by Jesus, defying death itself).

Bowie had pondered the connection between art and death long before this. Our collective fascination with and fear of death is at the core of his largely forgotten 1995 release “Outside.” An ambitious but ultimately murky concept album, its largely improvised songs derive from a Bowie short story, “The Diary of Nathan Adler,” included in the liner notes. Set in the near-future of 1999, Adler is investigating the ritual art-murder and dismemberment of 14-year-old Baby Grace Blue on the eve of the new millennium. Bowie plays the role of the detective as well as the oddball suspects: Ramona A. Stone, Leon Blank, Algeria Touchshriek. “Outside” marked the resumption of Bowie’s creative partnership with Brian Eno, a collaboration they hoped to continue but did not.

If the dystopian world of “Outside” sounds lugubrious and just plain creepy, Bowie was in high spirits when we spoke at an unusual hour for a rock star interview – nine a.m. – two days before he opened his co-headlining tour with Nine Inch Nails.

“….I embrace chaos.”

In his hotel room in Hartford, Connecticut, by phone

September 12, 1995

How are you today?

Pretty tired. I had a late night last night at the rehearsal. We’re in Hartford and we’re rehearsing in the new amphitheater they have there [the Meadows Music Theater, now the Xfinity Theatre]. We open on Thursday and we’re putting up the production, running through it for the first time.

Is there anything to do in Hartford other than rehearse?

There’s a glorious art museum [the Wadsworth Atheneum]. Visiting the museums is not a bad way to survive. I did it a lot with Adrian Belew on the last tour in 1990, Sound + Vision. We both got up pretty early, so we’d skedaddle to whatever was the interesting institution in a city and check it out. It’s kind of a nice way to lose yourself for a couple of hours before you come back to the reality of tour life.

I’m probably not the first person to say this, but you’ve made a weird record [“Outside”].

Yes, it does seem to be that way.

Did you write the short story it’s based on before or after deciding to work with [producer Brian] Eno?

We had already started a whole set of improvisations in the studio around March, 1994. Out of that came dialogue and landscape that was tied together, not even tenuously. All the elements were fairly disparate. Later in the year, around October, I was asked by an English magazine, Q, to submit a diary of the last 10 days of my life, a kind of celebrity corner thing they have. Mine was filled with “Got up, went to the studio, came home” [laughs]. It was really looking pretty mundane, so I thought, “Okay, let’s take one of the characters I’ve been playing around with, Nathan Adler. What would he have been doing over the last 10 days?” And it became 15 years of his life. That was my submission to the magazine. I used that as a skeleton to lay the music upon.

The story gets into ritual-art murder, which is a very upsetting concept to most people. What’s your interest in it?

I think it’s a confluence of events. First, we definitely perceive murder now as entertainment. It’s used to a massive extent in cinema. And pretty much it’s a space filler in TV. When there’s nothing else on they throw a bit of murder on or a trial or something. There’s the whole gladiatorial arena spectacle of somehow appeasing gods or looking at the fears and anxieties of the public that somehow motivates this need to witness or have familiarity with the very dark side of human nature. Plus this growing momentum in body art, which has been precipitated over the last 15 years or so with people like Kiki Smith and Damian Hirst and Ron Athey and Chris Burden. The idea of using the body as yet another medium, like wood or metal or glass or stone. Almost the politicizing of the body itself. Almost extrapolating on that in an allegorical fashion to have this rather dark, satirical idea of where art could go. I’m sure you know a writer, Thomas de Quincy. For those of us who grew up in the ‘60s, his “Confessions of an Opium Eater” was a kind of bible. At that time, in 1820, he wrote a small piece for Blackwoods, a London magazine, called ”Murder Considered as a Fine Art” which laid down exactly that theory. Sort of that classic idea of taking a life as something sort of ritualized. Lots of things came into it. It wasn’t a simple, direct journey. Even the surrealists, like Andre Breton, who said in the ‘20s, probably one of the greatest acts of art would be to go out into a crowd and shoot a revolver into it. So it’s something that’s been touching the artistic sensibility for more than a hundred years. It probably has something to do with coming to the end of the millennium. Appeasing the gods in some way, so that we can get thru to the next millennium.

Is such art a sick way of demanding attention? Or a comment on the sorry state of present civilization?

That’s right. It’s seen from both viewpoints depending on who the viewer is. The morality of any society is quite strange. In the finality, it’s decided by law what happens. People change their network of comfort by changing laws to make things acceptable or unacceptable.

The new album shows your interest in this extreme type of body art. [In “Outside,” murder and the mutilation of bodies have become an underground art craze; it is the job of the main character, Nathan Adler, to determine what is and is not an “art crime.”] Have you attended performances where this kind of stuff takes place?

No, I haven’t. About 20 percent of what I put in are fictional and the rest are real, But it’s very hard to tell the difference. But the most surprising one, like the Korean cutting off pieces of himself in the late ‘70s in New York, was not apocryphal. I checked back with Art Forum. I did quite a bit of research to see how many of these seemingly apocryphal stories were true. I’ve been pretty obsessed by visual arts ever since I was a kid. I’m a collector. I’ve been collecting art for about 20 years. It’s a part of my life that is very important to me. That extreme aspect is just a realization of how much it’s gathering momentum.

Do you have any body parts in your collection?

[Laughs] Not a one. I have a sardine in a small plastic box that was made for me by the British artist Damien Hirst. He puts sheep and sharks into huge glass tanks. He’s an enfant terrible in Britain. I think the best thing I’ve heard about him came from one of our critics, who said, “In the ‘60s Hockney created the swimming pool. In the ‘90s, Damien Hirst put a shark in it.” He has that disruptive and very confrontational approach to his work and, in fact, is now the leading light in European art.

Ooh, I’ll tell you something which happened subsequently to recording the album which was disturbing in itself. There’s a Dutch artist, Rob Scholte, who’s pretty well-known in Europe. He’s not that far away from Julian Schnabel in terms of status over there. One day, in December, 1994, he came down from his apartment and got in his car with his wife and he heard a ticking sound. Needless to say, his car seat blew up and he was left without legs. Within a week following that, one of his contemporaries had been down to the attempted assassination spot and filmed the wreckage, the crash area, and was using it as a performance piece in a gallery in Amsterdam. That’s not a hair’s breadth away from what was satirical. It’s quite amazing what is happening as we approach the end of this particular passage of time. And of course now Rob Scholte is doing performance shows where he makes great play over the fact that he no longer has a pair of legs. They still haven’t found out who blew him up, but there are all kind of theories ranging from a drug connection to a jealous artist.

So what do you see as the connection between this kind of art and rock music?

Well, if you just see rock music as another form of communication, along with literature and painting, film and theater. What’s the rock subject matter? What is it?

Anything?

I guess you answered your question. It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot. I’ve been writing quite a lot of prose these days. I’ve done a number of things for magazines and newspapers back in Europe, short stores and art reviews. It strikes me that if it were any other medium, an author being questioned about his subject matter would not be a proposition at all. It would be, how did he deal with it? Was it any good? Did it have any artistic aestheticism that was reasonable? A critique would be applied to it, but the subject itself would not be in question. I think rock is growing up. Those of us who are 50, say, like myself, and have not written for a generation, just see ourselves as writers growing older and write about what we find fascinating about society at the age that we are.

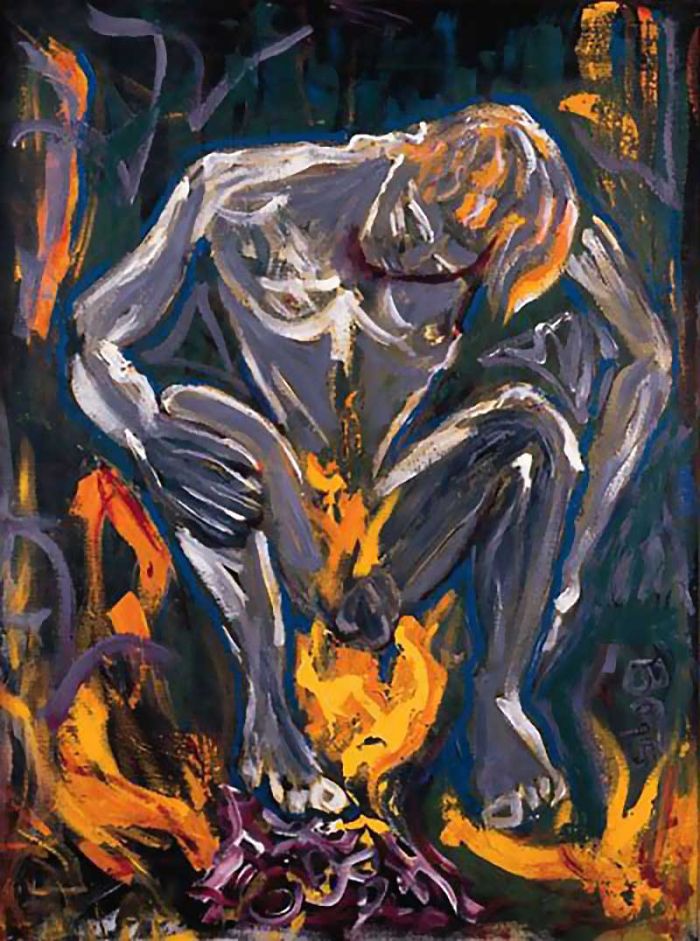

[Above: “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson”]

“Outside” is set at the end of the millennium. What are your thoughts about what’s in store?

I’m very positive about it. I think the greatest change that will happen on January 1, 2000 is that we’ll wonder what to wear that day. I feel these are ritualizations and symbolic acts.

But do you think it will be a significant date and not just something that exists on a calendar?

Absolutely. What Brian and I are trying to do is develop a series of albums that trace the last five years of the ‘90s. This is the first in this series or cycle of albums. [As it turned out, “Outside” was Bowie and Eno’s last recording together.] I think that what’s important is that we are using the narrative and the characters as, excuse the pun, a skeleton for the whole piece. It’s only the subject matter, it’s not the content of the album. The content is very much the atmosphere and texture of the music, that strange place that music indeed puts you which cannot be articulated. The story itself is semi-linear, so if you want to, follow it a linear fashion. But it’s not absolutely necessary. The pieces themselves can be autonomous, they are pieces of music on their own. It’s really about the audience and the interpretation of what’s being made. There’s no intent in it, there’s no meaning. I’m not a meaner. I don’t have this great thing that I have to say. It’s a collection of fragments of information, of ideas, that are assembled and produce a certain atmosphere.

Why did you set the story in New Jersey?

Yes, I wonder. I wonder. The lyric writing itself was fairly hazardous. What I did, I took a lot of areas of subject matter I’m interested in and wrote short paragraphs or pieces of poetry around those subjects and fed them into this Macintosh computer I have. I have a random key on it and it will randomize what I have written, just spew out reams of paper that I can use as fodder when I improvise with the band. So it was basically the Macintosh’s choice that it was New Jersey. But it was also a bit of England, too, with New Oxford Town.

Do you see chaos erupting as we head toward the millennium?

I think there’s a new perception of what our universe is like and that it’s been setting in for the past 10 or 20 years, since the ‘60s. The idea of absolutes feels like an anachronism in this era, with the way we live, with very fast event horizons and information overload. The actuality of chaos and fragmentation as being the reality, and the absolutes are in fact a fiction, an Apollonian device we use to carve parameters for the way we perceive and live. Which brings us to a kind of fundamentalism in looking at life and causes extremes of blacks and whites and inherently bigotry and intolerance through it. I think the idea of becoming comfortable with the idea of chaos is how we are progressing – that life and the universe are extremely untidy. Anything that pulls back the veil on that chaos is a step nearer a more realistic understanding of what our state is. So I embrace chaos. I’m a child of the ‘70s, remember. I’m pluralistic by nature. I always had the unfortunate facility of being able to see both sides of every picture. It wasn’t a question of not being able to determine which side I was on, but seeing that things didn’t have sides. It wasn’t as simple as that.

Is this in some way a response to controversy in the United States over [censoring] the arts?

It probably was in the mix, but we worked in so many different areas in putting this album together it wasn’t a predominant theme. So much of it was worked through in Europe where the sensibility is much different. The other things that went into it, Brian and I are both fans of a form of art known as outsider art. I, for the last 15 years, have lived next to the holy shrine of outsider art, an art museum in Switzerland called Le Brut, set up by Dubuffet [Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne]. He set it up because he felt he was terribly influenced by the kinds of art that were made by people who lived an unstructured life – in institutions, or hermits, or were ostracized by society for one reason or another. He collected the art that they made and toward the late years of his life opened this museum and put their work in it. That actually was a source of inspiration when we went in for our last three albums [“Low,” “Heroes” and “Lodger”] in the late ‘70s.

Subsequent to that, a new hospital has been set up in Vienna: Gugging. It’s absolutely fascinating, quite extraordinary. It was set up by two doctors who saw that many of their patients had an orientation toward the visual arts. They were painting and chipping away at bits of wood or whatever. So they got the funding from the local government to start a wing so they could develop and work on their talents. So many of these guys are now world-renowned artists in the outsider art genre. Brian and I took a couple of days there before we started working on this album to get some notion of what it must be like to be an artist who paints and works without feeling there is anything like judgement being made on him and who doesn’t have a bias toward one school of art or another. As far as he’s concerned there are no rules. And what he’s expressing is not for anybody other than the compulsion to make this work. It was just so exhilarating to see these people and talk with them and be with them. We tried to take some of that ambience when we went into the studio to work. The idea of working without knowledge or judgement, either self-judgement or of how the outside world perceives what you’re doing.

So they are mental patients, not artists with problems?

They are thoroughly institutionalized. They live in an alternate reality. And they just have to paint. They are completely driven. They just don’t stop. They’ve painted everything in sight, all the trees, the lawns, the whole building is colored! You’ve never experienced anything like it. It’s just sensational. It’s extraordinary how these strange Jungian symbols come through all the time: God figures, children, androgynous figures, religious symbols transformed and mutated into something else. It’s really the most extraordinary experience.

Does this have anything to do with what they call outsider art in the United States?

Yeah, folk art. It’s become watered down a bit from when this originally started. Frankly, this is what happens when commerce meets art. There’s not enough outsider outsiders to safely put on a convention, but you would be able to drag 20,000 people to New York if you throw in a few primitives and naif artists as well. So the boundaries of it now encompass anything that is not legitimate high art. I think that’s possibly a shame because it’s changing the nature of what it was. The other month I went down to South Africa for the first time. Some of the vibrancy in the art there is not dissimilar. It’s the idea of non-judgement, the idea of using loud, simple coloration. There’s no idea of it being vulgar. There’s no thought of taste. Taste is the killer of all art [laughs].

How did these concepts, these thoughts about art, transfer to the recording studio? I read that Eno decorated the studio with colored fabrics and set out paints and canvases for the musicians to use to explore non-musical means of self-expression.

Well, Brian, very cleverly, because of being what he is, which is basically a conceptualist, turned everything into a series of games once we got into the studio, to allow the musicians to not be who they are for short periods of time. He would create little flash cards for them in the mornings. He would create situations they would have to put themselves in mentally, intellectually, and then start playing from that point of view. So instead of going into the usual blues, which all musicians do when they’re asked to jam, because they are looking for common ground, so inevitably it’s some really wonky jazz piece or the blues. And you never go anywhere. So we changed the status of the beginning of these pieces and they came into them like aliens from another place. It opened up a whole area of improvisation.

;

[Above: “Hallo Spaceboy”]

Was this you turning your musicians into characters?

Well, we did do it in the ‘70s as well, to a certain extent. We did break their rules so they would have to play from another place. It’s an ongoing thing of Eno’s. It’s very much how he works. It’s how he redefines the studio situation that makes working with him so fascinating. Because he breaks down those areas where you feel you’re being judged. It continually comes back to that, because there’s nothing more inhibiting than if you think, “Oh, I’ve got to do better than I did last time” or “I have to do better than that person” or “People will look at this work and think such and such.” Once you can break down those unseen eyes you become far freer in how you can push the envelope of what you’re doing.

Did the musicians stay in character throughout the sessions?

I would imagine that within seconds of actually getting into the music he probably forgot the whole thing, once he got into it. It was the way he entered that dictated how the piece progressed. So he would come in playing in a particular way that would not be a blues in E. It’s very hard to explain [laughs], you should have been there. A piece that shows the extreme it could get to is “A Small Plot of Land.” That piece in particular was a first class indication of what happens when you put people in a strange place like that.

[Above: “A Small Plot of Land,” live at Wembley, November, 1995]

Well, “Outside” is certainly not a conventional pop record. There’s no obvious hit material.

Absolutely. It ain’t on there.

You keep defying expectations again and again. Does that mean you’re constantly disappointing record company?

Yes, it does [laughs]. But in this case, Virgin, my new label, and I are having a honeymoon at the moment. I do have to look for people that will allow me to work in the style I am used to because that is where I derive my satisfaction as an artist. I can’t work for an audience. And frankly, I have to forget any idea of expectations from anyone else other than myself. And my expectations are only that I will find some new information somehow in what I am doing.

But when you go on tour you do have to entertain the public, right?

We shall see. I’m afraid I’m not being too helpful there either. I’m not doing any songs that they’ll know probably, unless they know my material very well. I’m doing a great slab of work from “Outside,” which won’t even be released when I start the tour. And that’s joined with more obscure songs from the past like “Joe the Lion” and “Teenage Wildlife,” pieces I’ve never done on stage or have only done infrequently, a couple of times in my life. I wanted to do pieces that would jell with the songs from “Outside.”

When you did the Sound + Vision tour [in 1990] you said that you would never play your hits again. Are you sticking to that vow?

That’s right. It’s more than a vow to me, it’s an absolute necessity to survive as an artist. It’s extremely difficult to even conceive of performing things like “Major Tom” with any sense of integrity. It’s too worn for me, it’s not what I want to do. It’s very selfish, but it’s what I have to do to maintain momentum as an artist. I have to put myself in rather adventurous or hazardous situations, me personally. Many other artists don’t feel this necessity, but it’s one that I personally enjoy. I know that if I’m in a comfortable situation nothing much is going to come out of it.

So is that why you have Nine Inch Nails opening for you?

Exactly. It’s like, “How tough can I make it?” Plus I’m wearing a tank top and we’re playing sheds as it’s getting bitterly cold. I found that out last night. My god, it gets cold there. I’m terribly excited about that aspect of it [having Nine Inch Nails open]. One of the joys is that we’re working together. You might think the juxtaposition would never work, but in fact it’s incredibly strong when Trent and I work together. It’s jelled so perfectly it’s just great. We’ve worked out 20 minutes onstage together so far. Who knows what will happen. We might do the whole bloody show together! [laughs]. No, no. But that in itself is something worth seeing. It’s a really interesting combination.

What songs will you do?

Trent chose some of my things and I chose some of his and we worked them out together. At one point, we have both our bands playing together. [During the tour, as Nine Inch Nails neared the conclusion of their performance, Bowie and his band came onstage and both bands performed “Subterraneans,” “Hallo Spaceboy” and “Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps),” followed by two Nine Inch Nails songs, “Reptile” and “Hurt,” after which Bowie continued with his set.]

[Above: “Hurt,” live in Virginia, October, 1995]

Who’s in your band?

Carlos Alomar, Reeves Gabrels, Mike Garson. The new replacements. My drummer joined Soul Asylum, Sterling Campbell, but he recommended a close friend of his who’s really great, Zack Alford, who played on Springsteen’s last tour. On bass I have an American girl, Gail Ann Dorsey. She worked with Gang of Four and, I think, Tears for Fears. Eno’s role is taken over by – he doesn’t do any performing, especially not a tour, he’s got a lecture circuit going – so on synths we have Peter Schwartz from New York.

And will you be telling the “Outside” story?

The show is non-theatrical. It’s got delightful lights and that’s it [laughs]. I really believe in these pieces as autonomous pieces and I think they stand up in their own right, especially in between things like Jacques Brel’s “My Death,” which I haven’t done since 1973. It makes some kind of rationale, but not too much, I hope [laughs].

Nine Inch Nails are billed as co-headliners. How will that work?

Nine Inch Nails will open. They very kindly wanted to maintain their support position, which I’m thrilled by. This whole thing came about when Virgin asked if I would support the album and I said of course. I adore the music and want to do it live. Then I looked around for another act and I’d been reading and hearing a lot about artists from the new generation of bands and it was quite apparent that the work that Brian and I did, and the later work I did like “Scary Monsters” and “Station to Station,” was starting to have an effect on the newer bands over here. I read interviews with bands like Smashing Pumpkins and Stone Temple Pilots and, in particular, Trent Reznor, who in one interview cited the “Low” album as something he listened to almost daily when he was writing “Downward Spiral.” So I took the bull by the horns and phoned him up and asked if he’d like to work with me on the tour. He’d just finished a 14 month tour so he said okay, as long as we didn’t do more than six weeks.

Do you have any fear that people will walk out after Nine Inch Nails plays?

Now that’s extremely likely, isn’t it? [laughs]. You mean there are cynical people out there? I’ll have to fold the tour.

So you take this as a challenge?

Yes, it has to be that way. I don’t want a safety net. That produces nothing. It just gives you a great big fat bank.

You’ve talked about doing a series of albums following from this one. Are you thinking they would be similar in sound or much different?

I think it would sound completely different, even though it would be deemed part of the same cycle. One thing is I really want to put this murder to bed and move on to something else. But the whole approach might be completely different next time, with no narrative form. I don’t know. That’s what makes it exciting. Otherwise what you’re working for is some bloody alternative musical, which is not where I want to go.

But wouldn’t this be good material for a theatrical production?

Watch out, “Tommy”! No, I don’t think that will ever happen to it. My pipe dream is to get Robert Wilson. I imagine that by the time we finish these four or five albums that it will be the kind of material he’d like to work with. We could stage it as a one-off short duration piece, although with Robert’s input it will probably last for seven hours. So just bring your sandwiches and walk out during the boring bits. I have a fancy to have it produced like that.

Well, thanks for getting up early this morning to talk to me.

Oh, I get up far earlier than this. The result of stopping drinking is that you wake up at five. It never changes. No matter what time you go to bed, you wake up at five. I’ve been doing this for six bloody years now, waking up at five. I get up way early, we both do. My wife does too.

And what do you do in Hartford at five?

You phone Europe all morning [laughs]. I’ve got very small canvases with me, 10 x 8, and I’m doing a series of heads of everybody on the tour. That should keep me happy for the duration.

[Below: “Heart’s Filthy Lesson,” 1995]

Original 1990 Interview Audio with David Bowie: