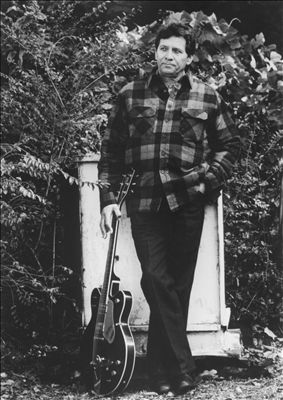

Dan Penn is far from famous, but most everyone – at least most everyone of a certain age – knows his work. Penn produced the Box Tops’ immortal “The Letter” and co-wrote a clutch of stone soul classics (“Dark End of the Street,” “Do Right Woman,” “I’m Your Puppet,” “Cry Like A Baby,” “Sweet Inspiration,” “You Left the Water Running”) covered by a lengthy list of artists including Aretha Franklin, Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, Solomon Burke, Dolly Parton, Etta James, Ry Cooder, Barbra Streisand, Linda Ronstadt, the Flying Burrito Brothers and on and on; his list of credits on All Music Guide runs to 1,262 entries and no doubt there’s plenty missing.

However much a behind-the-scenes player, Penn is a legend among one subset of music aficionados: Southern soul fans.

Original Interview Audio:

“Everybody was into Ray Charles…..” – Dan Penn

I first noticed Dan Penn the same way I’m sure many others did: by seeing his name as the co-writer of “Do Right Woman,” a track on Aretha’s first album for Atlantic Records, “I Never Loved A Man the Way I Love You.” He continued to pop up in the credits of other late ‘60s soul albums and at some point I understood he was connected to both the Muscle Shoals and Memphis soul scenes. Dan Penn became one of those names that I searched for. If Penn’s name appeared anywhere in the liner notes of a record, that was a near-guarantee I would like what I was going to hear.

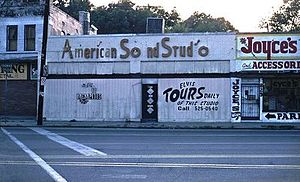

And at some later point I realized that Penn was white, as were most of his colleagues at Rick Hall’s Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals and Chips Moman’s American Sound Studio in Memphis. This was not quite so much as a mind-blower as seeing my first photo of Booker T. and the MGs and reeling from the realization that two out of the three MGs were white dudes (and, with their short, out-of-date and out-of-style haircuts and department store suits, exceptionally uncool looking white dudes at that), but Penn’s pale pigmentation was unexpected. Also thrilling. Because here was proof that racial harmony could and did exist, that blacks and whites could literally make beautiful music together. Clearly life in the South was far more nuanced than white liberal Northern preconceptions allowed. But I’d have to wait a quarter century to ask Penn how he and his cohort of pale-faced Southern good ol’ boys came to create bedrock classics of African-American music.

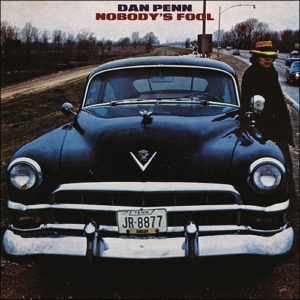

Penn finally got around to releasing an album of his own, “Nobody’s Fool,” on Bell in 1973. I had no idea of its existence at the time, because I surely would have bought it (and I would have been let down; too much of “Nobody’s Fools” sounds like demos geared to adult contemporary/country radio).

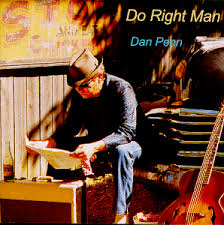

It wasn’t until 1994 that Penn, then 53, released his first and only major label album, “Do Right Man,” on Sire. Recorded in Muscle Shoals with the studio’s heroic session players – Spooner Oldham (Penn’s frequent songwriting partner), Roger Hawkins, David Hood, Jimmy Johnson, Reggie Young, etc. – Penn sings with easygoing authority as he covers a half-dozen of his best-known songs and four more. It’s laid back soul, the sound of someone doing what he likes to do and not trying to prove a damn thing.

While not any sort of commercial breakthrough, “Do Right Man” was enough of a critical success that Penn embarked on a rare tour the following year as the singer and guitarist in a duo with keyboardist Oldham. The twosome played the Wilbur Theater in Boston on October 29, 1995 (with singer/songwriter Tom Ghent the opening act), an occasion that provided a chance to interview Penn (by phone, in advance of the show) and see him perform.

Penn and Oldham continued to tour off and on for the next few years, and they released a lovely live album, “Moments from This Theatre” in 1999. Since then, Penn has self-released three albums in what he calls his “Demo Series,” on his own label, Dandy. He’s dressed in overalls on the cover of all three, looking more like a working farmer than a working musician. You can buy the CDs on his website, which claims that Penn, now in his mid-70s, still periodically goes on tour, now accompanied by another old Muscle Shoals chum, keyboardist Buddy Emmons. Maybe he’ll come play Boston again some day, but I doubt it.

October, 1995

By phone from Dan Penn’s hometown of Vernon, Alabama

Where are you today?

I’m way down here on my home ground. We come every opportunity we can. We have my wife’s folks’ old farmhouse that we fixed up. We come down here and sit on the porch and get away from everything.

Would you say you are part of the Nashville songwriter scene?

Yeah, I am. Not so much in Nashville. I live there, but I don’t write a whole lotta country songs. Some country. When I have an opportunity I play stuff to people. I send a lotta songs to Rounder (Records) and people like that who are still interested in rhythm and blues. It’s not the music of the day, but we still like it. Hearing Irma Thomas do a song you wrote is worth it all. Hearing her is almost enough payment. There are still some good ones around. [Irma Thomas would release an entire album of Penn songs in 2000: “My Heart’s in Memphis.”] I live in Nashville. I like it there. Sometimes I go downtown and play with the big boys, but mostly I stay out at the house and act like I’m in New Orleans. That’s the kind of music I really like.

Did the release of what many people would call your long overdue solo album on Sire [“Do Right Man” in 1994] have any effect on your life?

Well, not really. We did the album without anybody’s feedback. We were just trying to do straight ahead pop-rhythm and blues, the stuff that we wrote. And I was into that anyway. I don’t try to go on the blues side too much and I don’t go into country too much, I stay in the middle. That’s the kind of groove I like and that’s where the record is. That’s the ‘60s thing.

Did you start going out and performing more after the album came out?

A little bit more, yeah. First of all, coming to New York to the Bottom Line, it had been 25 years since I played a gig. I showed up up there and that’s how the record deal came down. I learned that an artist needs to show up somewhere and sing. I’d just as soon be in the studio cutting records. But I went to Europe and did some shows and I really enjoyed them. I started out that way, as a singer. So I began to enjoy doing some shows and I hope to do more. I hope to have a band together at some point. Right now it’s just me and Spooner [Oldham]. It’s kind of an odd thing. I think the salvation of it is that you can see the guys that wrote the song sing the song without any distractions. It might not be very glorious, but it will be real.

But you’d rather be doing it with a band?

Oh sure, if I’d’ve had time. This last year I’ve been building a studio in my house. But I do hope that in the future I can bring a band. But I have to say that me and Spooner playing by ourselves is probably something that will not happen many times. And we do have a thing together that we don’t do with anybody else, it’s just kind of our little thing. It goes back to the songs. Nobody knows the songs like we do. So we just sing ‘em and play ‘em the way we remember them. I hope it comes out good. With just one or two people you don’t ever really hit the groove, but you can examine them much better anyway.

Did you always want to perform or did you prefer staying behind the scenes?

Oh, I was pretty happy. People were cutting my songs, I was learning to engineer in the studios, I learned how to produce records, I got into all of that. I was pretty happy with all of that. In ‘71 or ‘72 we made another record and I made a record or two since that never came out. Every once in a while I’d talk myself into it or somebody would talk me into making a record, but I really like to make records on other people, the production and writing. I feel I’m at my strongest doing that. But I enjoyed that Sire record and I’ll be making some more in the future I hope. That’s my whole idea in building a little studio.

So you’ll do more for Sire?

No, it was a one record deal. So I’m looking for other record companies that would have interest.

Think you would you do more new material next time?

I hope so. There might be one or two of the classics in there. I’ve got quite a few that aren’t on the Sire album. I could do the same thing again, but I don’t like to do the same thing twice. Not in a row anyway. There’s “Sweet Inspiration” [recorded by the Sweet Inspirations], “Cry Like a Baby” [the Box Tops], a lot I didn’t do. “Out of Left Field” [Percy Sledge]. But the next record, I’m hoping to cut over the next two years, the best of the demos. I like to cut ‘em as I write ‘em and then put the best of them out. I’m looking for a spontaneous vocal. The vocals you get in the regular studio are okay. The last album was okay, they came out good enough. But sometimes when you just get through writing a song, that’s the best you’re ever gonna sing it. Right then. Because there’s just some real magic in that moment if you’re loving the song. If you don’t love the song there’s no magic. But if you’re really turned on by the song, there’s something right there in the singing that you’re not going to get again. I’d like to see those kind of vocals on the market.

Your songs have been covered by a lot of great artists. Do you have particular favorite versions?

Gosh, I’ve been very lucky. But I guess Aretha’s “Do Right Woman.” That’s about as good as it gets. But there have been so many more. I’ve been really fortunate in the people who have cut my tunes.

Is “Dark End of the Street” your most covered song?

I really haven’t sat down and tried to figure which one has been done the most but it’s right in there with “Do Right Woman” and “I’m Your Puppet.” Those three have probably been covered more than any of my songs.

For me, I’d have to say that James Carr did the best version of “Dark End of the Street.

Yeah, for me too. I really never heard anybody that came close, including my own version. I liked it so good, I tried to copy it [laughs]. Nobody does it like James. He’s the king of “Dark End of the Street.”

I read that you wrote it in the midst of a poker game?

Yeah, it was during the intermission of a poker game. We were in Nashville at what we used to call the disc jockey convention, and me and Chips Moman and [Papa] Don Schroeder were playing poker and we played and played and played and finally we took a break. Me and Chips went into another room and there was a guitar sitting there. I said, “Hey, I have an idea,” and he said, “Me too.” We must’ve spent 30 minutes on it and we had the whole song. Then we went back and finished playing poker. Yeah, it was a quickie. We went back to Memphis and cut it.

It sounds almost like something magical that you could write such a great song in those circumstances.

Co-writing, there’s a closeness of people. The closer you get to another songwriter, the more apt you are to write a song. Me and Spooner, we got to where we could just breathe – I could stop and he could tell me what I was fixin’ to write and vice versa. It was kind of a game. We wrote every night. And there was a space of time when me and Chips Moman were that way.

Do you write the music, the lyrics or both?

It is 100 percent equal in every respect. He’s playing the piano, I’m beating the guitar, he’s singing, I’m singing. I might be the one to say it, but he might be the one to think it. I know that sounds farfetched, but there is some thought transference going on when you’re on a heavy writing date that’s really coming off. If you’re really excited about it and really believe you’re on to something, the thought transference goes way up. On a mediocre morning that doesn’t happen. You work on a common sense level. But some days you’re way above common sense and that’s the good ones.

Do you still write regularly with Spooner?

Well, over the last couple of years we’ve gotten together a few times. He’s also doing a studio thing now, so this last year we haven’t gotten together. But we hope to keep writing songs together for as long as we can.

You and Spooner were two white guys writing soul songs in the South. Did people think you were black?

That happened some. People would say things like that. But hey, the people in the South always liked the blues, black and white. There was a time when it wasn’t so cool around here for the black people, [but] there was a closeness between the black and white people. In some eras it was bad, but in others it wasn’t. In our era it was not bad. There weren’t a whole lot of black people here, but the ones that were here were very nice and got treated nice.

Where did your exposure to black music come from?

I heard all that blues and stuff on WLAC, like every other kid in my part of the country. And after everybody heard Mr. Ray Charles, it was all over.

So you weren’t considered weird?

Oh, I was an average guy. I played in square dance bands and stuff like that. But I was a little bit weirder than the rest of them because I would scream louder than the rest of them. Most people would just sing the songs. For years, I would scream at the top of my lungs. I got fired a lot of times that way. I was a pretty wild kid. But I didn’t think I was different until I got to Florence [Alabama] and began to work with Rick [Hall]. My heart was all in black music at that point. But every white kid at that point was going around singing [he sings, imitating Ray Charles], “Tell me what’d I say now” [laughs]. Everybody was into Ray Charles and all those New York black guys, Ben E. King and Jackie Wilson, I was not the only one. It was everybody that rode around in a car and tuned into WLAC was into that.

So there you are in Alabama, blacks and whites working together in the 1960s. Did the folks in town look askance at what was going on in the Muscle Shoals studio?

A little bit, yeah, you could feel it. But nobody would walk up and start something with you. But when you were riding around with a black man in your car at the time, it was not too cool. Nobody was gonna shoot you, but you got the looks. You got the message.

People up North thought Alabama and George Wallace were the most prejudiced people in the world. Were you anti-Wallace?

It didn’t work that way with me. To be honest, I didn’t think anyway about any of it, I was too busy scratching something down on paper and going to the studio. I was working with black people, they was riding with me, I was doing anything I wanted to. I didn’t ever kick into the cause. I was always removed from that. I was not a marcher or any of that.

Did you feel that what you were doing was in itself a statement for racial equality?

I never considered that. I thought less about prejudice than anybody you ever met probably. It was all work. Back then in the ‘60s, I was working way too hard, night and day, and all that was nothing I ever thought of. I wasn’t into any of it, neither side of it. I was as far away from politics as you could be. I never thought about the work being political. I was just trying to get a hit.

So you didn’t care about the color of who was singing your songs?

Oh, I wanted it to be black. They were the ones who could sing the best. That was what I was into. I was into black music, I wasn’t into the black freedom movement. I was brought up in a place where blacks weren’t mistreated. But there was an attitude in the South, as there was in the whole country. People turn to the South and talk about segregation and the mistreatment of blacks, but the fact is that it was everywhere. This is just where it went down. But I was in the studio most of the time. I was in my own little world.

By the end of ‘60s the popularity of Southern soul music started to decline. Was that a difficult period for you?

Those were tough years for me. Seemed like I got lost during that period too. It seemed like the whole world got lost and I got lost right along with it. I began to do a lot more drugs during that time along with everybody else. It was not a good time for me. Musically, I experimented with every kind of music I could, and, in the end, I didn’t like any of it. All of the ‘70s was that way for me. It was not until after 1980 that I got sobered up. I was in real bad shape and I got sobered up through the church, through the Lord, and got back up on my feet and began to think again. I was really low, but I got to the point where I could start over. I got back to the music I love and I try to hang pretty close to that. But I’m not like I once was. Once I only wanted to hear black music. Any kind of music is okay as long as it’s good stuff. I’ve come around. some of it I don’t care for as much, but I’m not as narrow as I once was.

Did your down years in the ‘70s occur because you were frustrated by what was going on musically or because you’d tasted some success and suddenly had too much money?

I lived in Memphis during that time. I had my own studio. I had been with American with Chips Moman and he and I fell out. I got my own place and was drinking way too much. When you’re drinking or drugging too much, you just can’t think straight. It had caught up with me, because I had denied the Beatles and all these foreign groups and white groups. After Dr. King’s death I had to leave the studio and I just had a 10 year lull when I just looked at all the music from a kind of drunken state. Part of it was frustration that my music wasn’t happening. Part of it was that blacks and whites had come to a parting of the ways in studio settings. And part of it was that things had just moved on. I never lost the knack of writing a good song – sometimes I wondered, but I knew I could. The ‘70s was all a big mess for me.

Do you take pride in having an album out now or is songwriting still the main thing?

Well, I’m glad to have made that record. There were people who had heard of me, that the demos were the best, that Dan Penn sang great. That stuff would come around once in a while and haunt me. I felt it was something I needed to do. I didn’t care what songs were there, I needed to sing. Let the fat man sing, y’know? So I was glad to have the opportunity to do that. [A&R man] Joe McEwen at Sire, it was his idea to do half classics and half new stuff. I was determined to make a record even before I went to New York and then he offered me the opportunity. After the fact, I was glad that I did do some of the old songs. I hadn’t thought about the direction. I never think about direction. I’m more off the cuff. And I’d like my future recordings to be more that way. Direction is fine, but a record by committee is not fine. I want to go in and make a record that sounds good, then get through with it with no input. I’m pretty much of a no input person. The more input I get, the more confused I get. I already have 10 million ideas I’m fooling with in my own brain. Somebody else has an idea and suddenly there are 10 million and one [laughs].

Last question. Is this going to be your first time in Boston?

Yes. I’ve never been north of New York City.

The Box Tops: “Cry Like A Baby”